Interview

“Touch” and “Moor”

Janine Antoni performing Touch. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Loss & Desire, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Artist Janine Antoni discusses her video piece Touch and her sculptural installation Moor.

ART21: Can you tell me about your piece, Touch? Where did the idea come from for this work?

ANTONI: While making Moor, I had the idea that it would be interesting for me to walk on a rope. What I did is: I called Big Apple Circus and I said to them, “Can you lead me to someone who could teach me to tightrope?” And I got a few numbers, and I called up a fellow named Kevin O’Keefe. And when I got him on the phone, I said, “Do you think I can learn to tightrope?” And he said to me, “Oh yeah, walking on the wire is just like walking meditation.” And at that point I knew I’d hit the right person because I was learning to meditate at the time. And so, I bought a portable tightrope, and we set it up in my studio, and he came once a week to teach me to walk. And I would practice for about an hour a day, and it was an incredible process to learn to walk on a wire. It was almost like learning to walk again.

So, I practiced tightrope for about an hour a day, and after about a week, I started to feel like, “I’m now getting my balance.” And as I was walking, I started to notice that it wasn’t that I was getting more balanced but that I was getting more comfortable with being out of balance. I would let the pendulum swing a little bit further and, rather than getting nervous and overcompensating by leaning too much to one side, I could compensate just enough. And I thought, “I wish I could do that in my life when things are getting out of balance.” You know, when you have a hard day, and one bad thing happens after another? I sort of learned that I could just breathe in and sort of set myself back up onto the rope. The other thing that was really fascinating is I started to learn the bottom of my feet in a way that I had never learned before. If the wire is just a millimeter to one side or the other, I can feel it in my arms. I started to learn all kinds of things about the skeletal structure. About my sternum and my sacrum and how to keep them in balance. It was quite a beautiful process, learning to walk on the rope.

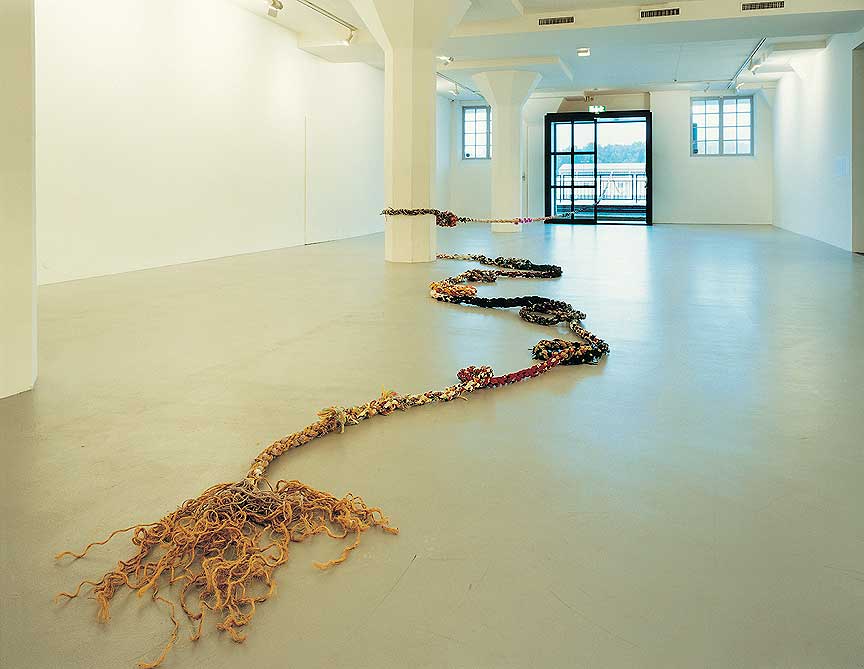

Janine Antoni. Moor, 2001. Dimensions variable. Installation view, Free Port, at Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthalle, Sweden. Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine.

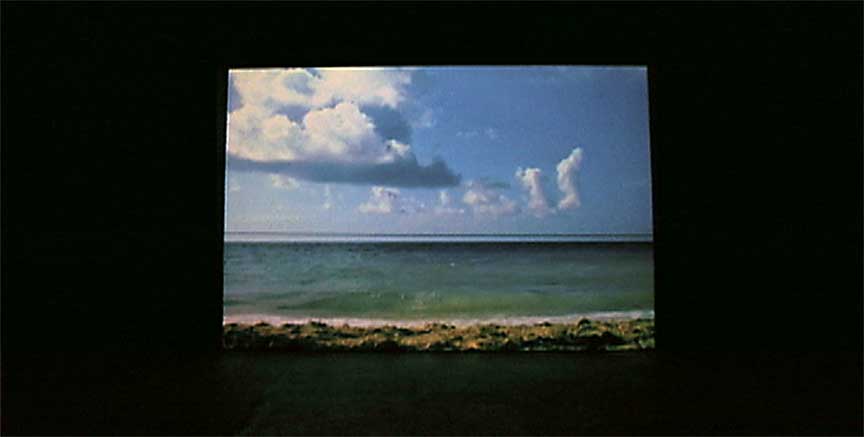

I had several ideas of where I was going to take that, in terms of my artwork. After going down many different avenues, I decided to make this work, Touch. And what I did is: I went home to the Bahamas, to the beach that was directly in front of the house that I grew up in. And I had a neighbor who is the head of sanitation services of Freeport, Grand Bahama. And he brought two tractors, and we hooked up the wire to the backhoes, so that we can use the shovel to go up and down, to create that wire to settle right on the horizon. We dug a hole for the cameraperson, my assistant Meg, so she would be low enough to line the camera up. So that, when I walked, I would just sort of touch the horizon. And I guess the idea came from thinking about what the horizon means to us.

My mother likes to say that she always encouraged us to travel. She had this Trinidadian expression: that we come from behind God’s back—that our island is so small that not even God recognizes it. So, there was always this idea that you had to go out and see the world. And for me the horizon was out there. It’s a very hopeful image: it’s about the future, about the imagination. And so, for me to walk in this place seemed very appropriate: it made sense for me to go back to this horizon, this ocean that I had looked at my whole life.

I realized that, although I probably could have manipulated the video as if I was walking all the time on the horizon, I thought it would have much more tension if I could walk along the rope and—as it dipped—that, just for a moment, I would touch the horizon, which would really talk about the incredible struggle to get to that place of the imagination. I encountered a lot of struggles along the way, with wind and the moving ocean and so forth, so it was very hard for me to balance on the wire. Which I think creates a kind of tension in the video, which served me well. And then, every so often in the video, the rope fades away. I wanted to leave the viewer alone with the horizon, to sort of be in their thoughts, to spend some time with the sound of the sea and think about what the horizon represented to them.

I call the piece Touch because it is about that moment or that desire to walk on the horizon, which is obviously an impossibility and only an illusion that can be accomplished through the video camera. And you can see I’m hardly balancing there in that place of my desire. Thinking about what the horizon means to us: it’s sort of a place of contemplation. But for me, I’m interested in it as a place that doesn’t really exist—that if we were to try to go to that place, the horizon would just recede further.

When I was learning to make the rope for Moor, I was reading a book written by Ram Das. The book is called Be Here Now. And I was sort of looking through the book, and it has these great line drawings. And I turned to a page that had a line drawing of somebody walking on a tightrope, and I thought, “Wow, I could be walking on this rope that I’m making.” And that was where the idea originally came from. And it went through many manifestations of me actually trying to make the rope, which still may be a piece, but this turned out to be one of the incarnations. And because Moor is made out of materials from my friends, I thought I could make a rope from materials of my life and walk it like a lifeline. So, it’s kind of funny that I ended up walking the horizon that I could see from my bedroom. In a way, I am walking my lifeline. My mom said to me, “Well, of course you want to walk the horizon; this is the thing you probably looked at the most in your life.” This is the image that I know so well.

Janine Antoni rehearsing Touch. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Loss & Desire, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: I had no idea that the location has such meaning for you.

ANTONI: It made sense for me to go back to this horizon, this ocean that I had looked at my whole life. Balance is an interesting thing because I think it’s a state we’re always striving for, but it’s an impossible state. And I think this piece speaks to that very much. And maybe the piece is more about you feeling comfortable with being out of balance. And that’s why just I named the piece Touch, because there’s only just one moment when everything comes together in the video. So, it’s kind of a crazy thing, to think you can walk on a wire; it’s unreasonable. It’s about the least amount of thing that you can walk on, so it’s really about walking on air. Balance is brought up in so many issues, I think, for all of us, to think about our lives and our need to be in control and be in balance.

ART21: Were you also interested in a kind of romanticism with the image?

ANTONI: Yes, I was interested in the romanticism of the landscape, of the seascape. It’s a funny thing because I kind of come from an idyllic place. This place is everyday to me in a certain way. But I know, when other people see it, they look at this incredible ocean. And I think it sort of plays with our romanticism of the seascape—but also that I’m like a giant walking on the horizon. You know that when I appear.

There is a tradition, of course, of depicting the landscape or the seascape, but there is also a tradition of the figure in the landscape. There’s a tradition in art history of the figure in the landscape. And I haven’t done much painting, but I know that it’s very difficult to depict the figure in the landscape because the landscape is so vast and the figure seems dwarfed in this vast landscape—and especially when you think of the horizon, which is, like, one of the most extensive images one can think of, and open. So, I guess this is putting the figure in a place that is sort of unexpected. I feel like a giant walking on the horizon.

ART21: How did you decide what to wear in the performance for the video?

ANTONI: Oh, well, I couldn’t figure out what I should wear. I didn’t want it to be too much about the circus. And I thought about wearing a dress or something that one wouldn’t expect someone to be wearing when they’re walking on a tightrope. And it’s always complicated because so much meaning is put into that. And it was my mother who said, “Oh, you should be wearing the same color of the sky.” So, I thought that that made a lot of sense to me, and I think that it worked quite well, that I sort of fade into the sky at points.

The whole idea to walk on a tight wire is to be in the sky. We know that from Philippe Petit, who walked between the World Trade Center [towers]: just the idea of being up there in the clouds is so extraordinary and such an image of freedom. Some of the things that the tight wire conjures up for us are this ability to float or to go beyond our physical reality. To fight gravity, really, which in a way we’re doing with every step. I mean, if you look at a little baby learning to walk, you see how [she’s] losing [her] balance. But as we walk, we’re losing our balance and gaining it with every step. And the tightrope just makes that show more.

Janine Antoni. Touch, 2002. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Loss & Desire, 2003. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: How did you get into doing public performances?

ANTONI: I sort of backed into performance. It wasn’t something that I intended to do. I was doing work that was about process, about the meaning of the making, trying to have a love-hate relationship with the object. I always feel safer if I can bring the viewer back to the making of it. I try to do that in a lot of different ways, by residue, by touch, by processes that are basic to all of our lives—that people might relate to in terms of everyday activities: bathing, eating, et cetera. But, there are times when the best way to keep people in that place, which for me is so alive and pertinent, is to show the process or the making. It’s always difficult to put myself there. It’s a vulnerable place. It’s very powerful. I think that the thing that is most dangerous about it is that I move the energy off the object, and I try to put it on the process. But somehow it gets stuck onto me. This is a tricky place for me, too. That’s why I so often only work with the residue, and I’m sort of in the viewers’ imagination when they look at the object. When I show myself doing these things, I know it will be riveting for the viewer, but I want it to be riveting for the right reasons, or for the reasons I’m interested in.

The thing about performance is: it’s very direct. There’s no mediation of the object between me and the viewer. And in a way, that’s incredibly satisfying because all I want to do is get close to the viewer. But it’s important in the process of looking at art that we reflect—that there’s a kind of self-consciousness that goes on. In my work, there’s something very immediate about my processes, something almost dramatic about the kind of things that I do. And a lot of times the removal, in the object, gives space for the viewer to not be carried away in these sort of extreme acts that I do. And so, that’s why I have to be very careful in the performative work, because sometimes I can lose the viewer.

ART21: How do you lose the viewer?

ANTONI: I want to speak to so much for the viewer. It really goes back to this idea that it’s about the viewer having a relationship with the object, or the process, but not with me. In fact, what I really want is for the viewer to bring the information of their life to the object and to take that information back to their life. And I have to be careful not to get in the way of that.

ART21: So, if you do a performance, you fear that they identify with you, the performer?

ANTONI: Well, I think you see it in all of my work in the sense that I go to the personal, but it’s not about me. It’s about the mother. Even though I’m using my mother, you know? I really want it to be about the viewer’s mother, all of our mothers. In a sense, I feel like I can be the most true if I go to my life and my experience. But in the translation into the work, I need to create space. I don’t know how else to put it.

Janine Antoni. Moor, detail, 2001. Dimensions variable. Installation view, Free Port, at Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthalle, Sweden. Courtesy of the artist and Luhring Augustine.

ART21: So, for example, in Touch, the tightrope walking takes place on video, as opposed to a performance with an audience?

ANTONI: What I’m doing with Touch in the video piece is that I started with this idea: why would we ever want to walk on a wire that’s half an inch wide? It’s crazy, a crazy idea. What is that desire? And I think that, when we look at the tight-wire walker, we think, “They’re walking on air.” And that idea just sort of triggers the imagination. It’s like—it’s the impossible. So, then I thought, “Okay, if I could walk on air, if I could walk anywhere, where would I walk?” And that brought me to the horizon line. It’s another impossible place to walk. It’s not a place. It doesn’t exist.

The video allows me to create the illusion. The video is like the wire. It creates one singular view, which allows me to rest on the horizon with the wire. Of course in the video, I only rest there for a moment. And I could have had a blue screen and manipulated the whole thing and seamlessly walked the horizon, but that didn’t seem so interesting to me. For me, it was really about: what is that desire? And to just be able to balance there for a second was a way of bringing you to the point of that desire and then taking it away. It allows all of us to think about where that comes from.

I’m not sure what this new sculpture I’m making with the hemp and the tightrope will be, exactly, but it will be about the fall. It will be about the impossibility of that illusion. And so, in a way, they’re going to be opposite pieces. The way it will function is that it’s sort of like making a fairy tale or a myth or something. There will be some people, maybe. I’m not even sure if it will be a performance. But if it is a performance, there will be some people who experience the reality of my fall. And then I hope my fall will transform the object. So, whoever walks into the exhibition will be able to unravel the entire story.

Then the people who experience the performance will become the storytellers. I thought about this because some of the artists that I love the most, or some of the artworks that I love the most, are artworks that I never experienced. They were performances that were stories told to me by my professors at school or by other artists. I suspect that they’re a little bit like a fairy tale or a myth because I think that they’re retold according to our lives and what we’re interested in at the time. And so, that story evolves and changes according to our needs. That whole oral tradition is so interesting to me. I don’t know, but that’s how I suspect it will function.

ART21: It’s interesting that you mention oral traditions, because the more I think about your work, the more frequently it seems to go back to something that comes out of myth.

ANTONI: Yes, I think you’re right. We could say that this piece is going to tell the Icarus story. But you know there are also many myths that have to do with spinning. So, it’s sort of a combination of different stories.

There’s this one story that I like very much, of the Three Fates. And one spins, and that’s Birth; one weaves, and that’s Life; and one cuts, and that’s Death. After I did Slumber the first time, I wove for about month. And then I had a dream that night that I came back to the show and someone had cut the blanket away from the loom. And I thought, “Oh, this is the story of the Three Fates.” And it sort of seems so telling about my struggle with letting go of the peaks. That was like the first night I slept away from the work. So, it was kind of a separation dream, I think.

I certainly don’t choose the story first, but my interests take me to the story, I think. And then I research, I read, and then that sort of influences the creative process at a later date. But it’s never that I want to illustrate a story through a sculpture but more that, somehow, these stories are in all of us, so they just come out. There’s something about my process that makes them come out. These stories are there to explain our lives to us, I think. And that’s all I’m trying to do—is understand my life by making these objects. So, it’s not surprising.