Interview

Childhood and Influences

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. Le Baiser/The Kiss, video still, 2000. Multi-channel video installation and projection, CD audio recording, and mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Max Protetch, New York.

Artist Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle discusses how growing up on different continents affected his artistic practice and the numerous influences at play in his work.

ART21: Do you think growing up on three different continents has an impact on your work today?

MANGLANO-OVALLE: I might have been somewhere around six when I finally realized that not everybody spoke English and Spanish. I grew up with parents that always had to shift the family from Madrid to Bogotá to the United States—this triangle. In each of those sites, both languages were always being used. My parents tended to gravitate toward other people who were also from Spain or Latin America. These became my aunts and uncles in the United States because we didn’t have any family here. So, I still call people who were professional colleagues and friends of my mother and father “Tio” and “Tia.”

ART21: Sounds like you had a very unusual perspective.

MANGLANO-OVALLE: The world was very small for me at a very young age. Lines between things did not exist. I almost had to learn that there were borders, rather than growing up with the notion that there were borders and then trying to dismantle them. It was the experience of moving great distances at a very young age. The first time I came to the United States, I was under a year old. But very soon I was back in Spain, and then in Bogotá. The trip was very natural, and soon it was not an event. So, that’s very much a part of my work and the way that I look at systems. They’re very fluid, and things that are at great distances are immediately there.

But I also had the idea that the world was so big that it was not in one’s control. My locale was not under my control. I moved from here to there, to a new language, a new school, a new neighborhood, a new city, a new country, a new culture—to cultures that seemingly were the same but radically different: the Old World, the New World, the [United States]. Growing up in that triangle between Spain, South America, and the U.S., the politics were always very different. You had to learn fast and catch up.

That’s played a significant part in the way I think about creating. I think I’m most comfortable when I’m not in control of systems. So, I often make work in which I almost attempt to make my hand disappear. I’m more comfortable with thinking that it’s not there—that the world is acting on the work or that the true generators of image, of ideas, are a vast compendium of people and factors rather than artists in their studios.

ART21: There were huge political differences between the countries you lived in.

MANGLANO-OVALLE: In Spain, you were under Franco. And then you watched as Franco died and democracy came, albeit a monarchical democracy. In Colombia, you looked at other systems of operations, or other politics that had kind of a history tied to it, colonialism and so forth. But it also had ideals—Bolivar’s ideals.

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. Search (En Busquedad), 2001. Radio telescope installation at the Plaza Monumental Bullfight Ring, Tijuana, Mexico. Photo by Alfredo De Stefano. Courtesy the artist and Max Protetch, New York.

ART21: Was art also a part of your upbringing?

MANGLANO-OVALLE: I grew up looking at art all the time, without thinking it was art. In Spain, you had the ability to walk into beautiful Gothic cathedrals, into a Romanesque church, or under a Roman viaduct. In Colombia, you had colonial rococo or something more indigenous. I remember coming to the U.S. and finding that, in Chicago, you really couldn’t bring anybody to see those kinds of old classical masterpieces. But Chicago had history.

For example, I have a strong connection to architecture in my work. If at a very young age you’re walking into these marvels in Europe and in South America, you’re not treating them as architecture. Then, suddenly in Chicago, the marvel is the nonexistent Gothic cathedral—replaced by something that’s specifically called architecture, modern architecture. We were in Chicago when Mies van der Rohe was building there. This is what the U.S. had to offer, this modernity. Nothing like it was happening in Bogotá or in Madrid. It really was a kind of marvel, and I captured it. So, there are concrete moments that affect one’s view of where you locate art, where you locate identity. And, in one case, modernity was locatable to a particular moment of looking at a building.

I remember, at the age of ten, seeing eighteenth-century casta paintings in a museum and not understanding them until somebody pointed out to me that I was in one of those paintings. They pointed to a Spaniard, and then to a mestizo, and then to this little child, saying, “There is a castizo.” To have a family member saying, “See, that’s your father, that’s your mother, and that’s you,” and then to find out, “Oh, you mean my dad is different than my mom? And my mom is different than my dad? And I’m a hybrid?” was really important because we traveled in circles in Latino culture where there’s less a concentration on distinct differences than a spectrum of subtle differences. The fact that you’re able to communicate across them is what creates a kind of identity.

So, figuring out where one fits in the world affected me early on, as did the idea that, even though you fit somewhere, you can move. That became a kind of strategy for me, and it still is. At the moment that I’m very comfortable making works about Mies, and everybody is expecting the next video project on Mies, I’ll shift and do a project on weather. The moment I have a body of work that is all about genetics and DNA, I’ll shift and do a project based on architecture or hidden systems of propaganda. Essentially, these are all of the same sorts of systems. I’m just tapping them from a different angle.

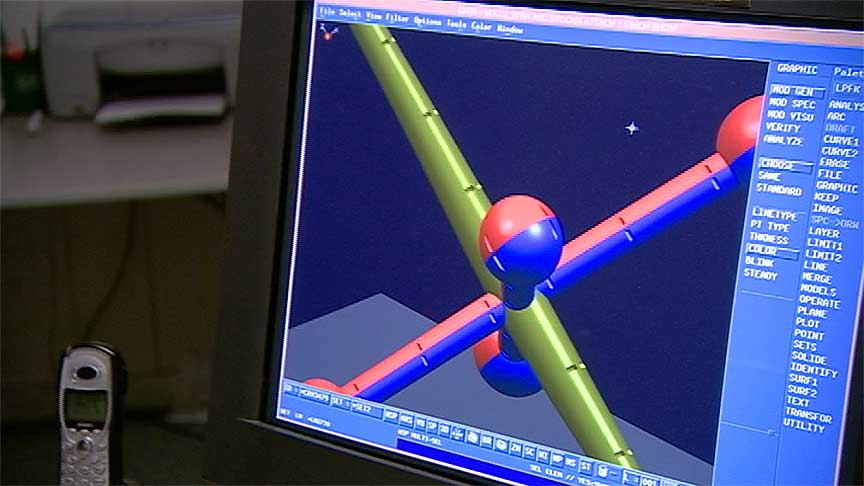

Making of Black Jack (2006) at ADM Works in Los Angeles, 2006. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 4 episode, “Ecology,” 2007. © Art21, Inc. 2007.

ART21: What role does science play in your work?

MANGLANO-OVALLE: Sometimes I think that people mistake my interest in science, thinking that I’m delving into science for its technology and its research. Really, I’m going through a kind of back door. I’m interested in science as part of culture, as a cultural manifestation. I think of art as not necessarily being made in the studio but through many conversations, interruptions, and different types of inputs, so that one can’t discern if one made the work oneself—or, if so, much has penetrated the process that the work, its authorship, is exploded and un-locatable. I also think that is part of science. So, when I’m working with a scientist, we’re not talking about science. We’re talking about philosophy, politics, music, and movies—about where we fit in the culture. People think that art fits solely in culture, and that science is not culture. I’m interested in science generated as a cultural necessity.

ART21: What drives your creative process?

MANGLANO-OVALLE: The creative process for me, whether it’s scientific or artistic, is driven by a number of forces. And one that I’m most interested in is desire, a desire for something that will change us. I often think that science and art are both contending with the desire for the new. Even at the moment, when we say the avant-garde is a lost cause or nonexistent, desire is still out there. And I think even the most critical and cynical artists have to acknowledge that little kernel that still connects them to that belief, much as a lapsed Catholic might still have a connection to belief.

So, when somebody asks me why I am dealing with science, I say that I’m not just dealing with science. And if I am dealing with science, I’m dealing with the image of science. When I made my first DNA portraits, it was not a response to the new technology of genetics. It was not about visualizing science. It was because all of a sudden (we had just had the O. J. Simpson trial in 1994) the DNA fingerprint was a new image. What really fascinated me was that abstract image and the idea that we, the public, incorporated it into our vocabulary and our understanding of image and of abstraction.

ART21: Your practice is both analytical and critical.

MANGLANO-OVALLE: Well, I think I always wanted to know how things worked, from a young age. I was in grade school, making Super 8 movies, but I was also taking apart my father’s camera and not being able to put it back together. I think that part of art is taking something apart and then realizing that maybe you can’t put it back together. So, it’s all about digging in and finding out why. I think part of my research is always asking, “How does something work? Why does it work?” How something works is an analytical process; why is a critical process. I need both. And there’s a skeptical quality; it’s what we call a Doubting Thomas. You have to stick your fingers into the wound to test it, so I do that.

Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. Black Jack, 2006. Carbon fiber and aluminum, 138 × 158 × 96 inches. Courtesy the artist and Max Protetch, New York.

ART21: You have a great interest in architecture. Did this start at an early age, too?

MANGLANO-OVALLE: I remember my most palpable experience with architecture was going up to the basilica of Zipaquirá, outside of Bogotá, where there’s a shrine. My mother and grandmother would go up there and bring my brother Ramon and me along. They would do the fourteen Stations of the Cross. This basilica is built into a mountain, which is also a salt mine. And Ramon and I basically licked the basilica all the way around. It was only when we came out into the daylight that we realized our tongues were swollen and cracked.

ART21: Your work is often engaged with challenging the way we understand things that already exist in the world.

MANGLANO-OVALLE: Oftentimes my projects mimic what’s already out there, as a way to understand it. For me, it’s a lot easier to ask the world why things are the way they are than to answer why I make things the way I make them. Maybe the way I make things is a way to answer for myself why things are the way they are, rather than to construct a different world.

ART21: You were raised by two scientists. How did this influence you?

MANGLANO-OVALLE: My parents came to this country, following grants to do research in cancer. The people around us were researchers, doctors, chemists. When you’re a young kid, you’re not interested in science. You hear it discussed at the table all the time, and it becomes part of dinner conversation. And it’s part of the same dinner conversation as politics or something cultural. I think that what my parents gave me was a way of looking at how the world is organized, rather than a kind of scientific structure for looking at the world. When I use science in my work, I am interested in the philosophical questions rather than the scientific ones.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2007 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.