Sonia D’Agnese has taught art to students ages 3-17 in the Maryland public school system since 2008. She is an Art21 Educator and National Board-Certified. She currently teaches Studio Art and Ceramics to middle schoolers. She takes a creative approach to art curriculum, balancing traditional artistic skill development with interdisciplinary learning experiences, focusing in particular on Social and Emotional Learning. She looks to contemporary art for innovative entry points to art-making that keep students engaged and confident that they, too, are artists. She has been an advocate for functional and supported inclusion in the arts in her district and continuously strives to bring her fellow educators together in dialogue with the goal of supporting and inspiring more meaningful and heart-felt learning environments for all.

Teaching with Contemporary Art

Experimenting with Socially Engaged Art

Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

Thanks to the creative exchange that is the Art21 Educators community, I am more skilled at implementing contemporary art teaching strategies such as designing the learning space in the spirit of a studio or laboratory. I have embraced the notion that, as an artist-teacher, approaching a unit of inquiry without a known outcome (or in art education language, product or exemplar) may be a better representation of an authentic artistic process than a yearly recycled art curriculum. By standing in a position of wonder and creation alongside my students, we can mirror each others’ creative energy. Working more intuitively, I let my understanding of my students guide my planning. Middle school is a time when friend groups and social status begin to take more of a center stage in students’ lives. Oftentimes as a result of negative influences from the world around them, they may start to form more closed circles of friends or have their self-esteem affected by bullying or exclusion. Excessive screen time coupled with having spent formative years alone or behind masks has diminished the ability of many students to connect at school. So I began thinking about how I could use contemporary art to support my student artists in their development, helping them to overcome isolation and exclusion in favor of reaching out to new people in positive face-to-face interactions.

Art21 provided many examples of artists who make community-building a part of their practice. Artists such as Linda Goode Bryant, Tania Bruguera, Daniel Lind-Ramos, Azikiwe Mohammed, and Rick Lowe all involve their audience or communities in their art, practicing what might broadly be called Participatory or Socially Engaged Art. Socially Engaged Art is art that is collaborative, often participatory, and involves people as the medium or material of the work and aims to help a community and/or create social or political change.

I asked students to consider how they as artists could bring people together. I prompted them to devise a way to involve others outside of our studio classroom, but within the building, in a socially-bonding activity. The collaboration, the social interaction, and the potential relationship formed would be the “product”created. Although I prepared by doing a lot of reading and thinking ahead of time, the process would unfold throughout the course of the unit, and what we were doing revealed itself gradually.

Collectively we looked to artist and educator Pablo Helguera, author of Education for Socially Engaged Art: A Materials and Techniques Handbook, to help formulate the “criteria” for our work. We looked at his project “Libreria Donceles,” a travelling secondhand bookstore that provides access to Spanish-language books and opportunities for community gatherings. Together we determined that the SEA (Socially Engaged Art) would be successful if it was imaginative and fun for participants, involved a collaboration or social interaction between the artists and participants, had some aesthetic element, and, most importantly, achieved the goal of forging new connections between diverse members of the school community.

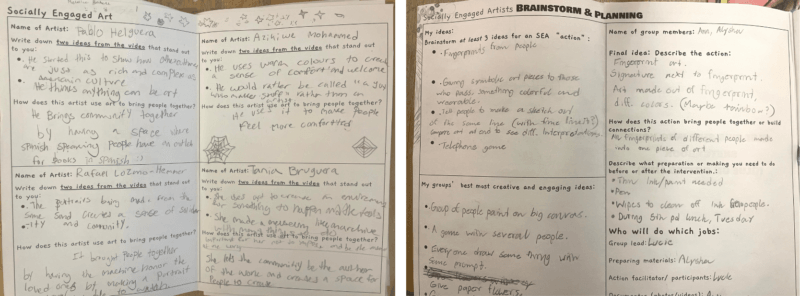

Discussions were supported by intentional questions posed as well as graphic organizers for students who were more inclined to write their thoughts before sharing out with the whole group. Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

The ideas students generated were varied and thoughtful. The implemented “events” included a collective story writing activity beginning with “Once upon a time,” in which different people added on to a story one phrase at a time. Another group invited students to a music listening “party” during their study hall period. While another group created a friend-matching social “application” using a Google Form questionnaire.

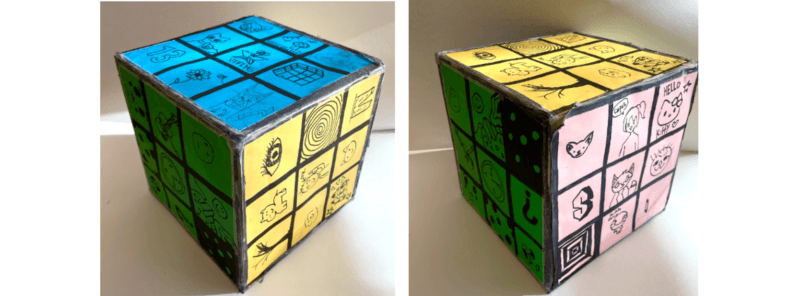

One student’s reflection states, “Our project is called 54 Friends. It is a Rubik’s Cube with 54 squares. By the end of the activity we hoped to meet 54 new people. We asked different people to draw whatever they wanted (as long as it is school appropriate). When we asked people to draw on the box they often asked “what should I draw?” So we asked them questions like what’s your favorite animal, what’s your favorite object, subject, colour. And because of this we got to know them better and talked to people we never talked to before. It is aesthetic because everything each person draws tells me something about them.”

“54 Friends” Rubik’s Cube. Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

In an often monotonous system where students are tightly controlled, following a fixed bell schedule with limited permission to move freely within or outside the classroom, this experience gave students freedom and responsibility to be in charge of organizing themselves and coordinating logistics. They were able to orchestrate events rather than being passive participants. This meant a lot to early adolescents who are eager to take on more autonomy.

Courtesy of Sonia D’Agnese.

It was a stimulating novelty for students to be given a creative prompt that did not necessarily involve the use of traditional art materials. It was a new concept to have full-reign over their ideation and to think of collaborative brainstorming as CREATING. Entering the realm of conceptual art by creating an experience rather than a tangible object eliminated the critical pressures of having to make something that “looks good”. Students learned to appreciate that “creativity” is also about finding novel ways of doing things, being open to new ideas, and finding solutions to any obstacles presented. As Linda Goode Bryant says in speaking about her artist collective, JAM, in “Friends and Strangers,” “It never was about objects, it never was about commerce, it was about creativity and frankly JAM was an artwork for me.”

I continue to look for ways to expand our reach beyond the school building and to integrate more conceptual art making into the curriculum. Most importantly, I know that sustaining newness and discovery as an artist-educator requires me to continue to experiment, facilitating learning experiences in which outcomes remain unknown for myself and my student artists.