Interview

Looking at Pictures: A Painter’s Education

Elizabeth Murray in her Manhattan studio, 2002. Production still from the "Art in the Twenty-First Century" Season 2 episode, "Humor," 2003. Segment: Elizabeth Murray. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

In this interview, Elizabeth Murray talks about her own personal history as an artist, how she began creating as well as the struggles she’s encountered over the course of her career.

ART21: When do you first remember making art?

MURRAY: Well, I drew when I was a kid. And I remember it very clearly because I got a lot of praise for them. I drew pipes and elephants. I have a very clear memory of drawing the elephant and realizing that it was actually like an elephant. Like, how to make that shape, and how the ears and the trunk were the distinguishing things. And then drawing a pipe, somehow, just that image. And then I remember—and I actually have this drawing—starting to draw figures. I drew a boy and a girl in my mother’s address book. And just, somehow, I could do it. I must have been around three or four years old. I could draw, and I got a lot of praise for it. My parents just loved it and told me I would be an artist. And here I am.

ART21: That’s so wonderful and so interesting, in that it manifested so early.

MURRAY: I don’t know if it’s the case with all artists, but I was very drawn to it. I loved to draw, and I did it all the time, did it kind of obsessively. It was a way of expression, and it did help a lot. I’m sure that people liked them and responded to them. So, it was a communication and something that made me feel good, too. I think the thing I remember the most, when I was little, was the excitement of being able to draw something. Like, figuring out how to draw a horse, having that capability. You know, how many bones there were in the leg, and where, like, the leg bent, and the excitement of just realizing that if I focused, I could do it. And with practice, you get better and better at it. Those are my primary things. In grade school, I would draw pictures of horses and sell them to my little friends. And it was miraculous to them. And I guess I kind of realized it was a skill and that being good at this or that made me feel good about myself. I sold them for maybe five cents or so. I thought it was a pretty good deal.

ART21: Were there other early influences?

MURRAY: I don’t know if this is a real memory or something that my mother would tell me, but we lived in Chicago up until I was eight. And my parents would dutifully take us to the Art Institute or to the Field Museum—which I loved. And running around at the Art Institute and being fascinated by this painting that I thought of as a rabbit. I thought it was a painting of a rabbit; it was a Kandinsky painting. And I’m sure it’s still there at the museum, too. I know it’s still there. But when I saw it years later, when I was a student there, I kept looking at it to see if I could find the rabbit. And it took me a while, and I did put it together, but it was amazing to me. There must have been some hook up there, for me. My mother was very proud because this was a totally abstract painting. So, they just thought I was, like, this little genius that was going around interpreting the paintings for everybody.

I remember finding it really exciting to look at the paintings. Of course, I never was in a museum again, after my parents left Chicago, until I went back to go to art school. But that’s a real memory. And then the other things were just the things that all kids liked—like Norman Rockwell, Walt Disney cartoons, Bob Kane (or whoever it was who drew Superman), Captain Marvel. I looked at comic books and Norman Rockwell, who I thought was an absolutely great artist. I loved his illustrations. And I wanted to either do that or have a comic strip.

Elizabeth Murray in her Manhattan studio, 2002. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Humor,” 2003. Segment: Elizabeth Murray. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: How would you connect all those early influences to the work, now?

MURRAY: I know the shapes are always referred to as cartoony. And they are cartoony and blumpy and rounded and inflated and sort of wacky. Norman Rockwell—I don’t know exactly if there is a connection. But I am sure it is all back there someplace; it’s just layers. I don’t think there is anything you really love that doesn’t stay with you for your whole life.

ART21: Is there any particular Rockwell image . . .?

MURRAY: Not really. I mean, I could name ones that I liked, like the boy and girl at the soda fountain. I have to say that there was always an element in it where it just wasn’t real. I mean, my life was not like that, like the happy family at the Thanksgiving table. And maybe that was part of what everybody loved about Rockwell—that it was all so sweet and unreal and completely not like real life. He painted the big American dream, an illusion.

ART21: Are there any other sources that were part of this stew of imagery?

MURRAY: I think that the most important thing was that my parents were so supportive of art and my being an artist. After we left Chicago, we lived in a little town in Michigan. I went to grade school there and then a little town in Illinois. Nature and the outdoors—that part of my life was a very powerful force for me. I really liked being outside. And I don’t know if this has anything to do with my images or anything, but I liked knowing what flowers were and what trees were, and I liked studying and looking at them and seeing how all those little segments went together to make a whole. That was a very pleasurable experience for me.

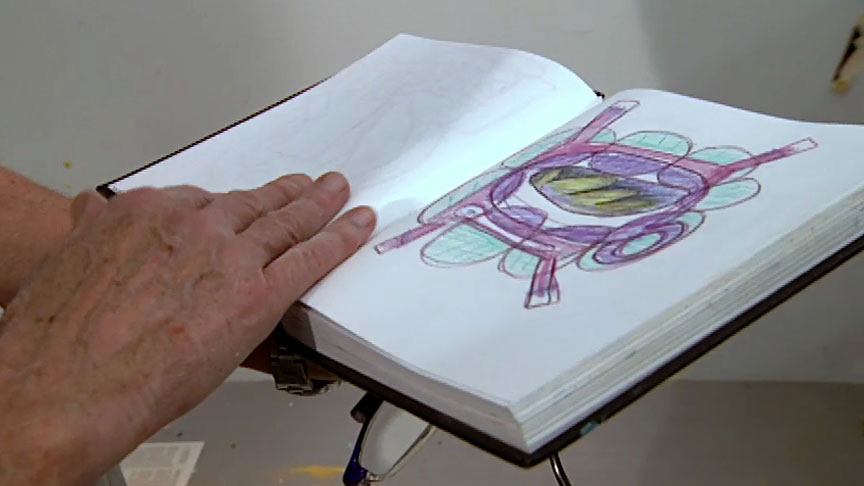

The other major thing would, really, be high school. I had a high school teacher in Bloomington, who was a very different person for this little town in Illinois. She taught high school art, and she was dedicated to art. She was really influential for me because she was so sure that it was an absolutely elevated thing to be an artist. She loved artists; she loved art. She took our class a couple times up to Chicago to the Art Institute, which is the first time I ever saw a Picasso painting. There was a big Picasso show there, and that probably would have been 1957, the year that Sputnik went up. And she was just an amazing teacher in her enthusiasm and belief. She was also very tough. She didn’t give praise easily and was very demanding. And she got me started on making a notebook, a sketchbook. And that was a huge thing for me. I found myself with a book that I could really draw into and write into. She was single-handedly responsible for getting me a scholarship to the Art Institute of Chicago. She talked this art group into paying my first year’s tuition, or else I never would have gotten there. Her name’s Elizabeth Stein. She is really a fantastic person, and she is still alive. I think she is around ninety-seven years old and lives in Chicago.

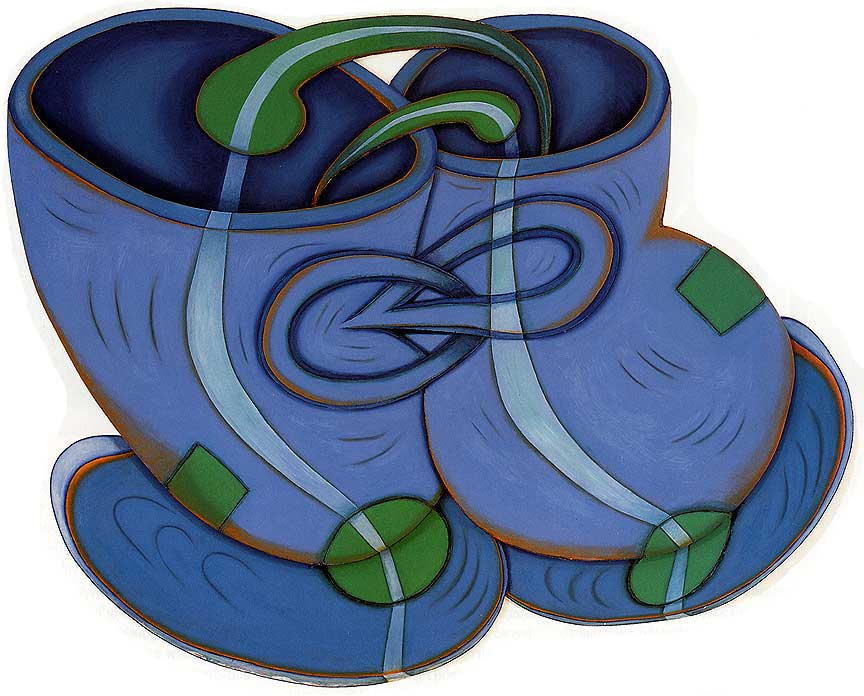

Elizabeth Murray. Stirring Still, 1997. Oil on canvas on wood; 92 × 115 × 7 inches. Photo by Ellen Page Wilson. Courtesy of The Pace Gallery, New York.

ART21: A good teacher can change your life.

MURRAY: She really changed my life. And it’s hard to say—I mean, you don’t really know what would happen—if I would have finally gotten myself back to Chicago and to art school, if it was destiny or fate or whatever it was. But she made it a lot easier.

ART21: Was there another person after that?

MURRAY: Well, she’s still in my life, in a sense, but—no. The Art Institute was a very different experience. It totally changed my life to go to school there. It really opened the door for me. And when I arrived, I was going to be in advertising/design—be an illustrator, be a cartoonist. And it took about a year of walking through the galleries—because the school was right in the back of the museum, so to get to the school, you walk through the galleries. And I started to see these paintings—which I hadn’t seen since I was, like, maybe six years old, really—and meet different kinds of people. I mean, there were people there, the likes of whom I’d never seen before in little Bloomington, Illinois. Like, guys walking around with beards, and poets, and they weren’t afraid to say it. They were very political. There were still men there from the Korean War in 1958. They were really serious. And people read books very seriously and did their work very seriously.

I absolutely fell in love with that world. I think, as much as I wanted to be an artist, I wanted to be different the way they were different, because it felt like freedom. Instead of being trapped in your little Pendleton skirt and your bobby socks and your saddle shoes, you could wear big, heavy, black boots and put blue makeup on and say what you thought. You didn’t have to be a nice lady anymore; that, in itself, was a big experience.

But the teachers were very tough. They basically seemed to be there to teach you that you had no hopes and no prospects, and being an artist was one of the most impossible things in the world—and you’d better realize that, you know, this was a life of suffering, struggle, and you weren’t going to be any good anyway. (LAUGHS) And that was the way it was! So, you know, that was hard for a couple of years. You took solace with your peers. And that wasn’t very much. That wasn’t very nice either, because it was primarily a male world. There were a few wonderful women around who were very helpful, my own age. There was one [female] painting teacher, Andrene Kauffman—I’ll never forget her. She was much more nurturing then the men, truly. It was just the reality with most of the men there. But the men were very hard on each other, too. Nobody was giving out any compliments there. I had to really find a way to believe in myself.

ART21: How did you do that?

MURRAY: I think I did it by looking at the paintings upstairs, in the galleries. I would go up everyday, and I would look at this particular de Kooning painting called Excavation. And I would do a dance with it—like, “Oh, he went this way” and “Oh, he went that way” and “Oh, he smudged this”—feeling the depth of that painting. When you look at it from a distance, it looks like this roiling, boiling pot of paint. Except the order is within it, is in that paint. And when you go up to it, you begin to see the layers of it, how the yellow goes over this white and blue—and I realized he scraped that on, and then he did this over it, and I deconstructed the painting. And I would go back down to my painting, and I would try to do it. And eventually—I never got that good. But it made me start to feel my body and my mind, my mind letting my arm make the decision—like intentionally, like control.

I began to get the control, and when you start to get the control, then your feelings can start to flow. And once that starts to happen, you get on the track, and the train starts moving. And it’s got stops and twists and turns, but something happened for me then, when I got to that point that just linked me up with it. I realized this was going to be my life. And there was definitely a point where I really almost chickened out. I just thought, “This is going to be so hard, and I should really get some kind of a job where I can help my parents, and I wish my parents hadn’t told me that they approved of this because then I wouldn’t feel like they were pushing me into it. Maybe I just want to do this for them.” I went through all this stuff, and I was going to quit. And I didn’t, because I didn’t know what else to do.

Elizabeth Murray in her Manhattan studio, 2002. Production still from the “Art in the Twenty-First Century” Season 2 episode, “Humor,” 2003. Segment: Elizabeth Murray. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

ART21: Was there anything discouraging in 1958 about all of the so-called great artists being only men?

MURRAY: Well, nobody said that to me, exactly. Nobody said, “You’re a girl. You can’t do this.” The only time that ever came up was once, when this nice young man said to me, “What’s a nice girl like you doing in a place like this?” Referring to the Art Institute of Chicago. And I guess I was upset by what he meant, like: “You’ll never be able to deal with this. This world is too rough and tough.” Interestingly enough, you know, you think of the world of art as being so much different: it’s not like football, you know; these guys are more sensitive, they’re different. But I think that maybe there was a masculinity to it, in a certain way, that I wasn’t really that aware of. I just wasn’t paying any attention to it.

I just knew it was hard. It was just very, very hard, and it was very, very different. And I felt like, “I’m going to get out of here. I’m going to go to California or something and get a job.” And I think at that point I may have even sort of resented my parents’ approval, feeling like, “Wait a minute, who wants to do this, them or me?” And then I didn’t. This was, maybe, in my third year of school, and I went back to school and I never really thought about it again, except to complain, “Why am I doing this anyway? This is so horrible. This is so difficult. This is not any fun!” It’s not what people think it is.

ART21: Why did you go on?

MURRAY: I think I just had it in me. There’s wasn’t anything else that I could do. I couldn’t think of anything else that I could do; and also, I loved it. It is about making things, and it’s about expression, and it’s about creation. It’s not in any kind of highfalutin, fancy way—it’s very basic. And I think it was such a great need for me. And I realized I discovered it—painting, making art—as something that I could do and that I really, really wanted to do, just for myself. Just completely for myself. And actually, in lots of ways, it felt lucky. It felt very, very lucky because not only are you doing it, and trying to do it better each time . . . So, that is inspiring, in a way.

I love art. I love painting. I love visual arts. I love films. I love reading. And to feel myself—to be trying to be a part of that—felt really important to me, and a real goal. And, of course, at the time I did say to myself, “I want to be a great artist.” I mean, it wasn’t stated in words, but within myself, that was what I was saying. And that goes away, in a sense, after a while. That stops being this goal—because the goal is more to keep doing it. My fantasy was that I would get to a certain point, and I would know what I wanted to say, and it was pcht (SOUND EFFECT)—you were on this straight and narrow road, and you would never swerve, and you would just do your work then. And that’s not the way it is, at all—it just isn’t the way it is. You get off the path and then get back on again for a while, and you trip along, and then suddenly you stumble, and you’re back on again. I don’t think that process ever ends. And sometimes I do think, if I had known what I was getting myself into, in terms of following this path, you know, “Would you? No, of course, you wouldn’t do it.” Maybe I would. But you don’t really know.

This interview was originally published on PBS.org in September 2003 and was republished on Art21.org in November 2011.