Interview

“The Last Days of Pompeii”

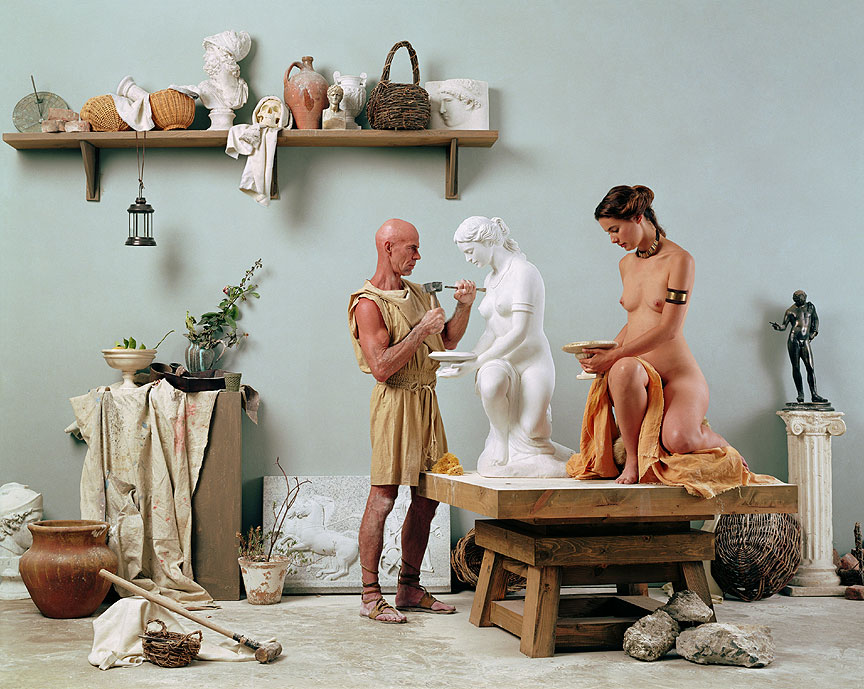

Eleanor Antin. The Artist’s Studio from The Last Days of Pompeii, 2001. Chromogenic print; 46 5/8 x 58 5/8 inches. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Artist Eleanor Antin discusses her photographic series The Last Days of Pompeii.

ART21: Why is time travel something that’s of interest to you?

ANTIN: I’ve got this love affair with the past. When I was kid, I wanted to have been an ancient Greek. We’re talking, like, five years old, six years old. I was fascinated with Greek mythology. And I was passionately in love with the sculptures (I’m from New York, originally) at the Metropolitan Museum—all those pathetic, broken people. It’s sort of like a mausoleum of cripples; it’s pathetic. I just fell in love with them. When I was a little bit older, I used to feel up the guys, and every now and then I’d get caught. When I was in high school, I used to play hooky and go to the Metropolitan and feel up Perseus and all the poor fellows. And sometimes a guard would catch me and say, “Don’t do that!”

But anyway, I have this love affair with the past. I wanted to be an ancient Greek. And one of the reasons I wanted to be an ancient Greek was because I would already be dead. And I was very aware of this. You know, even as a child you can be very logical. I was very aware that I would be dead. If I was dead, I would no longer have to go through all of the disasters and difficulties of living—which I already knew, having seen my desperate mother and father, was a rather difficult thing to accomplish. And so I thought, “Well, I’m already dead, but I will have lived an interesting life.”

The past has haunted me forever. In fact, when I did Pompeii, I never used to like the Romans as much as the Greeks. But I started realizing, as I got older, how appalling the life of women in Greece was, as opposed to the life of the Roman women, which was infinitely better—hardly very good, but certainly much better. The Greeks were more Oriental, more Arabic in some senses, and so, what I gravitated to was the image of Pompeii and what devastation was for the Romans. But it started with the Greeks.

You can find anything you want by going back to the past. You don’t even have to look. The metaphors start erupting all over the place. I’ve always loved the past because of the relations that I could make as an artist, with the present. I don’t remember this once it’s finished, but I do all this enormous research. Once it’s done, I kind of forget it, and I don’t remember it too well. Otherwise I would be carrying a trash pail in my head . . .

ART21: Did Pompeii come out of previous works? Or, how did the process of making this piece evolve?

ANTIN: Pompeii is a photographic sequence. It’s directing a whole host of actors placed in another historical period, and it deals with art, theatricality, and with what I think is our present-day situation. I was coming down the scenic route, looking at La Jolla, and there she was: the town was laid out on this incredible bay—like Pompeii, which isn’t exactly on a bay, but it’s filled with these beautiful, affluent people living the good life on the brink of annihilation. And in California, we are slipping into the sea, eroding into the sea, living on earthquake faults. And we finished this piece two and a half weeks before 9/11. So, the relationships between America as this great colonial power and Rome—one of the early, great colonial powers—were extremely clear to me. And I think it’s pretty much clear to everybody from the work.

Eleanor Antin. The Death of Petronius from The Last Days of Pompeii, 2001. Chromogenic print, 46 5/8 × 94 5/8 inches. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

ART21: The association between the United States and Rome is implied. It’s never made explicit.

ANTIN: One of my favorite art periods is the Rococo. I guess I have a Rococo relation to art making, in that there is always a game-like quality. I don’t like dealing with something head-on, in which I would say, “Yes, America, the U.S., and Rome—how close we are!” Okay? That, to me, is kind of klutzy, and it’s also two-dimensional. And it isn’t artistically interesting.

I want to present this image of the relationship that I had through the eyes and through the guise of nineteenth-century academic painting—because we are dealing with England and France, who invented Rome, in a way. They invented Rome to help glorify their own roles as great colonial powers with India and Africa and whatever they were colonizing. And especially the Brits: they had an enormous fascination with Roman subjects and obviously did see themselves in that guise, as the new Rome. So, I thought that it would be interesting to see our relationship through the eyes of nineteenth-century salon painting, which I’ve always loved anyway. It’s such campy painting. Lord—I’ve finished the work, so I can’t remember any of them anymore. I told you!

I also wanted to have someone’s eyes: a single character, who would be a Pre-Raphaelite woman, who would look and watch and observe everything in her wheelchair. She’s in a wheelchair, and only in the end and final picture—which is the only one that deals with the devastation and the destruction—is she standing up. Once the disaster happens, she stands and walks.

ART21: Is she like a surrogate for you, your eyes? Your alter ego?

ANTIN: Yes, she is, in a sense, the surrogate for me and then becomes the surrogate for all of us who are looking. She is watching. She’s ensconced in the nineteenth century. The works are presented in a nineteenth-century ambience. They are done in the style of the nineteenth-century salon painters, and they are dealing with Rome and a great colonial power on the eve of its destruction—in its innocence, in its glorious, mad, crazy innocence.

ART21: Coming upon the relationship between Pompeii, Rome, and La Jolla, California: it seems so inspired and effortless.

ANTIN: No, these things take time! (LAUGHS) Yes, I work very intuitively because there is a kind of poetry to all of these works that I have to come to. And as I say, they all unpack. Like, I’m dealing with this relation between us and Rome, and then I’m unpacking that to include—what is the other? Who else did that? England, France, the nineteenth century? What kind of work do they have? Well, they invented Rome. It’s not so simple as that, but it all kind of opens up, and at some point I just sail through.

Eleanor Antin. The Golden Death from The Last Days of Pompeii, 2001. Chromogenic print; 58 5/8 × 46 5/8 inches. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

ART21: How did the series come together, in terms of all the people you worked with?

ANTIN: It’s like shooting a film. And it’s not the first time I’ve done that for a big photographic piece. Obviously I did it with One Hundred Boots, but the boots are very easy actors to deal with. They don’t weigh that much individually, but when you have to schlep a hundred of them, they kind of weigh a lot. Up hills and down hills, and they don’t argue with me. When you are dealing with people, actors, you have somewhat of a different situation. Not that they argued with me; everyone was delighted to wear Roman clothes and be Romans.

Pam Whiden, who has been my assistant for many years, was in some sense the producer. She helped to see it through. She’d get me all these people to interview because I was very particular about who I needed. There were people who we couldn’t use. It’s very funny now because of my new project, Scenes From An Imaginary Movie. It’s based in the late ’30s/early ’40s—Second World War, middle Europe—and these exiles with their suitcases and their lives and their pockets and their guts are kind of moving from country to country.

And I have S.S. men in that, also. I remember speaking to one of the actors and I said, “Oh, you will be a marvelous S.S. man. Will you be in my next piece? We’re shooting at, probably, the end of the next summer.” And he said, “Oh, my family were German.” And I said, “I didn’t know that, but I know by looking at you that you will be beautiful, you will be wonderful. Okay?” And then he called me up a few days later and he said, “You know, I’d really rather be a Roman.” And every time I see him, he says, “Yeah, I’ll do it, but I wish I could be a Roman.”

Now, the Romans weren’t very lovable, but everyone takes enormous pleasure wearing these decadent, gorgeous robes in this villa. The actors had to be put together. I had to work out every image.

ART21: Where did you stage the photographs?

ANTIN: It was staged at my friend Marion McDonald’s villa in Rancho Santa Fe, California. And if anyone is dancing on the edge or the brink of destruction, I suppose it must be Rancho Santa Fe—lately called the richest community in the United States. Marian is a classics professor in my school, and she happens to have had this place for many, many years. It is incredible and very Italianate. And we brought in our own columns and whatever we needed, our own frescos and whatnot. And we shot one or two things in other places like the Salk Center, but basically we shot it at Marian’s.