Interview

Humor, Personas, and Yiddish Theater

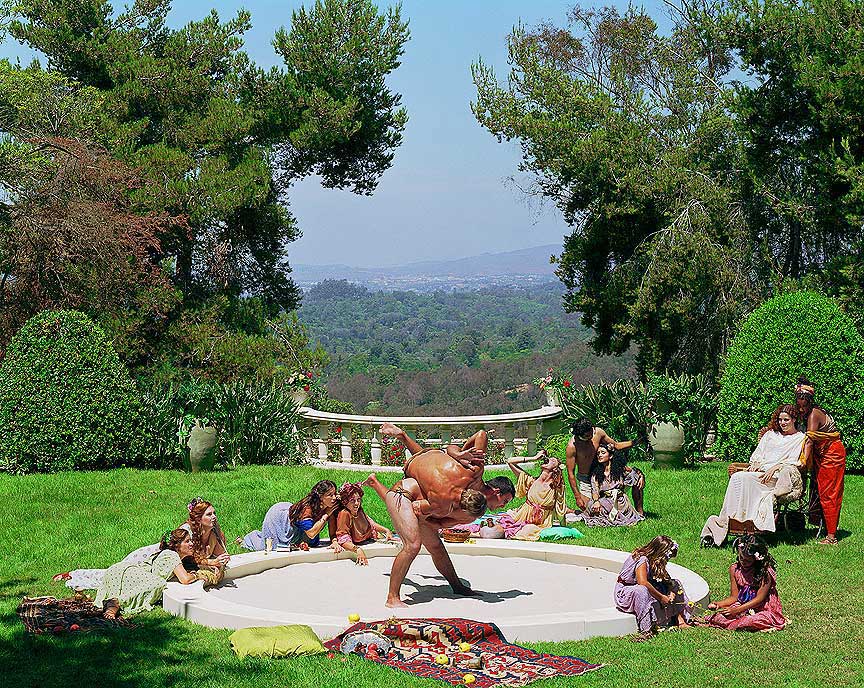

Eleanor Antin. A Hot Afternoon from The Last Days of Pompeii, 2001. Chromogenic print; 46 5/8 x 58 5/8 inches. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

Artist Eleanor Antin discusses her past, and work’s relationship to humor, role playing and performance.

ART21: How do you view the different kinds of humor you’ve used over the years?

ANTIN: Well, I don’t know about different kinds, but I know that I always tend to see the funny sides of things, even when my grandmother died. She died when I was a teenager, and my sister and I went to the funeral. And after the funeral we went to where the graves were. And I didn’t know much about cemeteries, but I knew what they looked like. We started walking, following the people who were going to my grandmother’s grave. And then, as we were standing there, and they were doing whatever they were doing, I nearly fell over this little white marble stone—and it said: Mother. And I burst into hysterics. (LAUGHS) I was laughing in the midst of this event that was quite tragic for my father, who loved his mother very much. I was in a state of total hysteria, and I was aware fully that I was laughing. There were dead people, and it was somebody’s mother. I remember my father coming and holding me tight and saying, “I didn’t know you loved Mother so much.” And I said, “Oh, yeah.” I made believe I was crying. Here I was laughing, and I made believe I was crying.

Another time is when I got married at this Justice of the Peace. I’m not into weddings—never was, never will be—but we went there, and we thought it would be fast, short and sweet, and over. And the guy—he came in and said suddenly, “Hello, hello! Do you, Eleanor, take this man!” I took one look at him and what he was saying, and I cracked up. I started laughing hysterically, and my sister, who was one of the witnesses, started laughing hysterically and David, my husband, was holding onto my hand. And I suddenly had this realization: “Oh my God, if I don’t stop laughing, they’ll say I’m too immature to get married and they’ll send me home.” I thought that was what they were going to do. So I just said, “Boo hoo,” and I made believe I was crying. I figured you were allowed to cry at a wedding. So I was crying, “Boo hoo hoo hoo,” but meanwhile I was laughing.

To make this long story short: for me, the richest experience is when it’s laughter and tears together. And I know that sounds very Jewish, and perhaps that’s part of the Jewish kind of humor I was brought up with. It’s like endless humor and at the same time, it’s “Oy!” I like it when it has those layers: that depth of richness, human experience, and suffering that it goes along with. And I think all my work—I mean, some of it—is just downright outrageous and funny, obviously. But it plays, even that stuff that looks like the most obviously ridiculous. There is, I think, a relation to human experience that gives it more of a rich layer than humor on its own. I think any person who works with humor, any really self-respecting comic, is going to feel the same way.

Eleanor Antin. Constructing Helen, 2007. From the series Helen’s Odyssey. Chromogenic print; 61 × 105 3/4 inches. Edition of 5. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts. © Eleanor Antin.

ART21: Is your family an influence on the work you do today—like, your mother?

ANTIN: Well, my mother, yes, that was the first great love of my life. Until I was able to free myself from the enormous pull of her influence, I suppose she was the only love of my life. She was a very interesting, very multi-layered woman. She had been an actress on the Yiddish stage in Poland, and she came here to an immigrant’s situation and became enormously depressed. She eventually pulled everything together. She had enormous strength. Instead of going into the Yiddish theater, which was actually quite interesting at the time, she found most of it very vulgar, which she called shunt, and she didn’t want to deal with that.

Instead, she worked a lot and then went into business and owned hotels. And her hotels were artworks. They were rather incredible. She went bankrupt on each one of them, which was unfortunate, but at the same time my mother cared more about the entertainment that happened on cabaret night than how many people were registered. So, unfortunately she went bankrupt, but at the same time the places were marvelous. They attracted a leftist/Russian/Polish/German/Jewish intelligentsia, with a great love for Yiddish culture—those kinds of hotels. As the people were getting older and as they started dying off, then she got fewer clients. She was a very creative, very interesting person . . .

ART21: What was it like, seeing performances with your mother when you were a child?

ANTIN: Well, my mother didn’t always know where our next meal would come from. In those days, she would cash a check on Friday, and then it wouldn’t go through until Monday when the banks opened. And then we would have no money over the weekend. But we would go to a concert at Carnegie Hall on Sunday afternoon. It was, like, a dollar and a quarter, and then afterwards we’d go to an Italian restaurant. Often there was one right down on 57th Street that wasn’t entirely inexpensive. And then, rather than leave a bad tip, she’d leave a good tip and then she’d say, “Alright, now we have to walk back and forth and find someone we know, so we can get money for a cab to go home.” And we would. She knew so many people because of the hotels, and she was a famous person within this small group of people. They were all so cultivated.

So, at some point we would see somebody, or else we’d walk home—all the way to 109th Street. It wasn’t bad for us. We’d have fun looking in the store windows, laughing, telling jokes. And she sent me to art lessons at MoMA, at the Museum of Modern Art. I had ballet lessons. My sister was a wunderkind pianist. She was always at the best conservatories. She used to get scholarships, but still, there was a certain amount of having to drag us. Those were the things that were important.

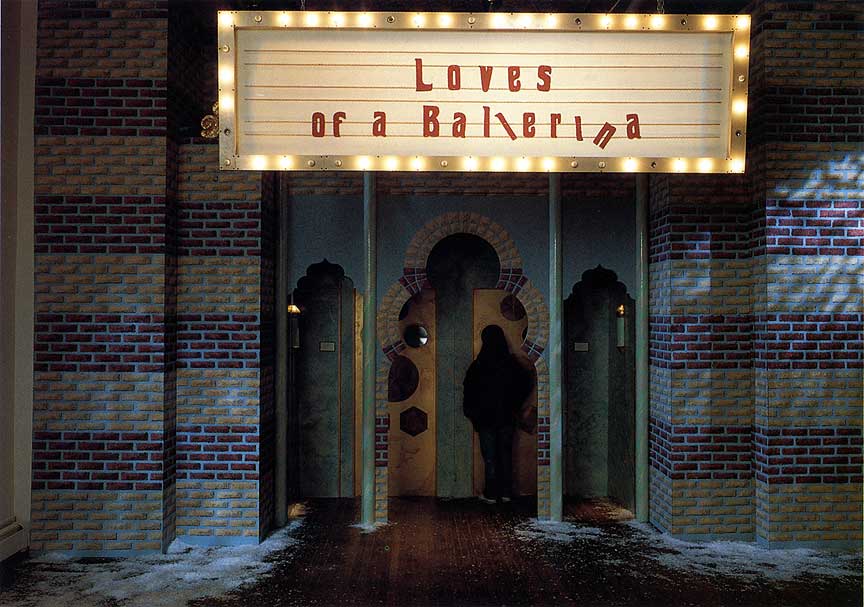

Eleanor Antin. Loves of a Ballerina, 1986. Filmic installation; dimensions variable. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

ART21: So, a rich cultural life is part of growing up in New York City?

ANTIN: Growing up in New York is really fabulous. I know everyone thinks, “Oh, God”—you know, dangerous place—but in those days you could certainly go on the subway. Kids could do everything. We could do everything on our own, and there is an enormous amount of activity that one can take part in that is just plain interesting, including theater and museums.

ART21: You started out working as an actor. Can you describe the trajectory between theater and visual art?

ANTIN: I used to think that I didn’t have a self. I didn’t have a self that was mine, and I literally decided on being an actor when I decided, “If I don’t have a self of my own, I can borrow other people’s, and so I’ll be an actor,” which I liked doing anyway. I liked hamming it up and everything. So, I became an actor, and I got some roles and things, and I was in Actor’s Equity. But I found the kind of stuff I was called on to do—the few times I was called on to do them—was just stupid. I went back to my first love, which was writing, and then I left that. I was moving through all these different art forms. And it wasn’t until conceptual art started coming in—with its possibility for mixed media, for not being stuck with particular genres—that I could make use of all these talents of mine. Not because they were talents but because I liked them. I enjoyed playing with them. And so, when that happened, that’s when I started doing the kind of early conceptual work that was the start of my art career.

ART21: That’s when you were participating in art happenings?

ANTIN: Yes. Fluxus and Pop opened up all sorts of possibilities with collage, with borrowed imagery, with whatever. So, I was just picking up from all over, like a scavenger, and transforming possibilities on my own. Sure, wonderful stuff is being done now, and wonderful stuff will always be done. But there was something about those years, the ’60s and ’70s, that was so alive. There was so much excitement in literature, in art, in pop music. I don’t think anything can compare to the pop music of the ’60s and early ’70s. I think I was being fed by my milieu and, yes, I was in from the beginning.

ART21: What did you first enjoy about role playing?

ANTIN: Role playing was about feeling that I didn’t have a self. And I didn’t miss it. It’s not as if I suddenly was this pathetic person without a self; it was just fine. I just borrowed other people’s or made them up. And it’s something that continued when I started working with personas because it was a very good way of dealing with a lot of the political and social issues that were of interest to me. And also particular intellectual interests that I had, like theater and self-representation.

So, I took on the King, who was my male self. As a young feminist, I was interested in what would be my male self. So I figured, “Oh, I’ll put hair on my face.” The other possibility was a little bit difficult, so I put a beard on. He became my political self. And then, my most glamorous, wonderful-woman self in those days was the Ballerina. And I had taken some ballet lessons a number of years before, but I really essentially taught myself from a book, standing still with a chair in front of a mirror. And I was a very good dancer, standing still.

I found that these characters had this marvelous quality of being like an onion. You know, you peel an onion and then there’s more skin, and you keep peeling, and then you peel and you peel. Of course that’s a romantic image because you’re crying all the time you’re peeling, you know, and I was sort of laughing most of the time.

But they did tend to unpack, and what happened is that they became richer and richer and more complex, especially Antinova. She became the black ballerina and danced with Diaghilev. I did all this studying about Diaghilev and the ballet, and I made my own ballets where I could deal with other issues that interested me.

You know, in some ways, if you look at Lichtenstein: he put everything into the Ben-Day dots. That was a great art-making machine he had, a marvelous art-making machine. And I had a marvelous art-making machine: my personas. I never knew where it would go. I could always open up into something else, until I decided I didn’t want to make art as somebody else. Until I decided I really was me.

Eleanor Antin. The Angel of Mercy, 1977. Eleanor Antin, Myself 1854 (Carte de Visite) from The Nightingale Family Album. One of 25 tinted gelatin-silver prints, mounted on handmade paper with text; 18 × 13 inches each. Courtesy Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

ART21: Who’s being interviewed right now? Are you really yourself these days?

ANTIN: As a matter of fact, I no longer make my persona works. I stopped when my mother was dying of Alzheimer’s and was losing her memory, and I started remembering all that wonderful Yiddish culture that she used to tell me about. And then I did my Yiddish silent film, The Man Without A World, as Eleanor Antin. Though of course the film is done by this supposedly imaginary Yiddish Russian filmmaker in the ’20s named Yevgeny Antinov. So, in a sense, I did do it through another persona, but somehow it always felt like it was me, even though it was him. I mean, I’m not insane; I knew it was me.

I wanted to do all of Antinov’s oeuvre. But I couldn’t get the money to do it. I wanted to do his complete oeuvre, until his final film in the ’50s, a sort of grade-Z sci-fi flick. I only did a few films of his. And after that, I started doing other works. The Last Days Of Pompeii is an Eleanor Antin work. There are no personas involved. And there are some people who actually find that distressing. They expect me to be in all of my pieces. And I say I am in all my pieces, even if you don’t see me.