Teaching with Contemporary Art

Creating authentic connections using Big Questions in my classroom

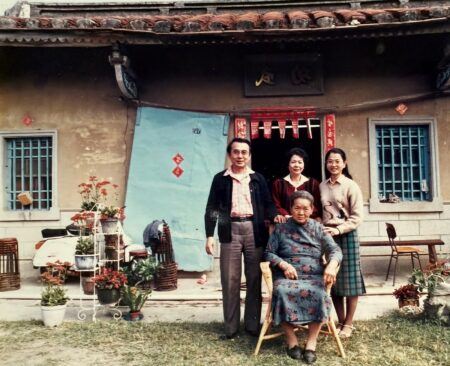

IMAGE: Photo by Thomas Dareneau.

In 2013, I attended my first Art21 Educators Summer Institute in New York City. One of the sessions was led by Joe Fusaro and Jess Hamlin, in which we discussed asking students Big Questions. If you’re not familiar, Big Questions are the kind of thematic, overarching questions that you pose to your students that expand far beyond studio technique. Some Big Questions that we had explored previously in my school were “How have artists used art to better communicate ideas?”, “What can we learn from art of the past?” and even, “What job opportunities are there for artists?” During the summer session, the discussion leaders proposed their own Big Question for us: “What Big Questions do you ask yourself when thinking about your classroom?”

I needed to really consider it. I have certainly taken a lot of time to think about what questions and tasks I was going to ask of my students, but I never spent a lot of time thinking about what questions guided me as a teacher. Later that evening, I returned to the Big Questions conversation and I had an epiphany. I was contemplating how to design a lesson revolving around the Big Question “What does art do?” I was trying to figure out how to wrestle this question into a project for my classes, and I was really struggling; this was a huge question and I wanted to do it justice. Then it hit me: what if instead of asking my students “What does art do?” I start asking myself, “What can art do?” Prior to that moment I was looking at art as a historian, focusing on things that were done in the past. This simple word change allowed me to think of my art room as more of a place of action than a place of reflection. I decided to rethink not just my lessons, but my entire approach to teaching. I decided to rewrite my curriculum focusing on students’ needs before teaching skill sets. Looking back, I now realize that I was beginning to work toward Social and Emotional Learning, though this was years before I ever heard the term Social and Emotional Learning. For me at the time, this was revolutionary thinking. We had enjoyed a very successful studio program and I was hesitant to move away from what was already working. I would need to take a step back from focusing on studio aesthetics and now put my attention into trying to create a safe space where all students could openly discuss and address real personal issues through their work. I was excited to try to become something more than a studio. By asking Big Questions we might be able to meet some of the non-academic needs of students that teachers of other disciplines could not.

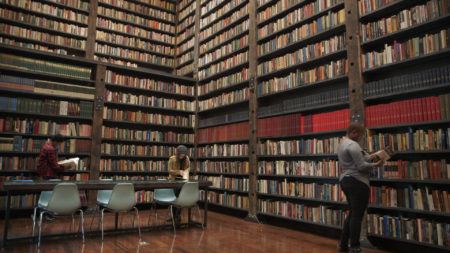

IMAGE: Photo by Thomas Dareneau.

This was a lot to take on and would require a lot of restructuring, so I tried to start small. I looked at successful lessons from the past and thought of how I could still teach skills but put the real focus on the student’s social and emotional needs. One of the lessons I am most proud of, came out of a lecture that a heard a few years later. In 2016, artist Laylah Ali did a presentation with the Summer Institute about her “John Brown Song!” project. As much as I enjoyed learning about her project, it was something she said during the Question & Answer segment that really captured my attention. I remember Ali sharing with us that she wanted to do a project with her students that helped different generations understand each other. She said that she wanted to create a vehicle where her students would illustrate the experiences of someone at least twenty years older than themselves. She was hoping that this project would create a personal connection and understanding between the generations.

IMAGE: Photo by Thomas Dareneau.

Ali’s idea immediately struck a chord with me. I was looking for a project that would connect students with adults they admired and looked up to. I thought that if students could talk to adults about defining moments, maybe they could learn positive life lessons from people they care about. In order to give a structure to this lesson, I took Ali’s concept of illustrating other people’s experiences and added it to a lecture that I already taught about symbolism. I asked students to create a motif using symbols based on the other person’s experiences. By using symbols, all students would be able to participate no matter their skill level, and we’d be able to keep personal information private by not sharing the meaning behind the symbols. To start the project, I had students interview an older person who was a positive influence in their lives. The students asked their subjects to reflect on a pivotal moment in their own lives and to explain how it affected them. My students had to take that information and break it down into symbols that their subject would recognize. One of my students chose their mother as the subject of her project. When my student was much younger, she had a physical condition with her hands that required many medical visits to a faraway hospital. Her mom explained that the multiple drives back and forth from the hospital taught her humility, how precious life is, and how to never take anything for granted. For the illustration, the student researched the facade of the hospital and used the distinct window pattern from the hospital as a background. She incorporated X-rays of little hands as a symbol for herself; to symbolize her mother’s devotion, she counted up her doctors’ visits and multiplied that number times the miles required of each round trip. After the project, my student said she was glad that she selected her mother because this was a time in her life that her family didn’t talk about much and this was not only an opportunity for her to learn about her past but also be able to say thank you. For me as an educator, this was an unexpected but very welcome outcome. These Big Questions created moments of real connection and meaningful art.

IMAGE: Photo by Thomas Dareneau.

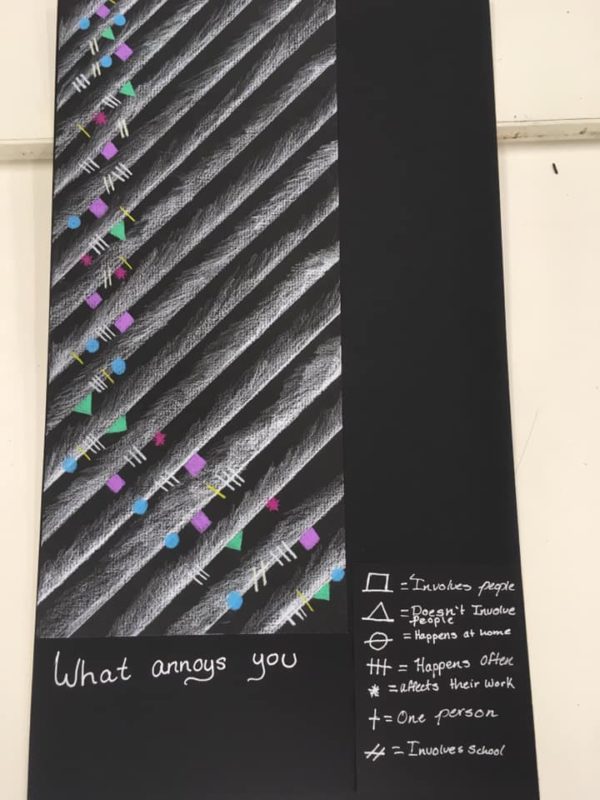

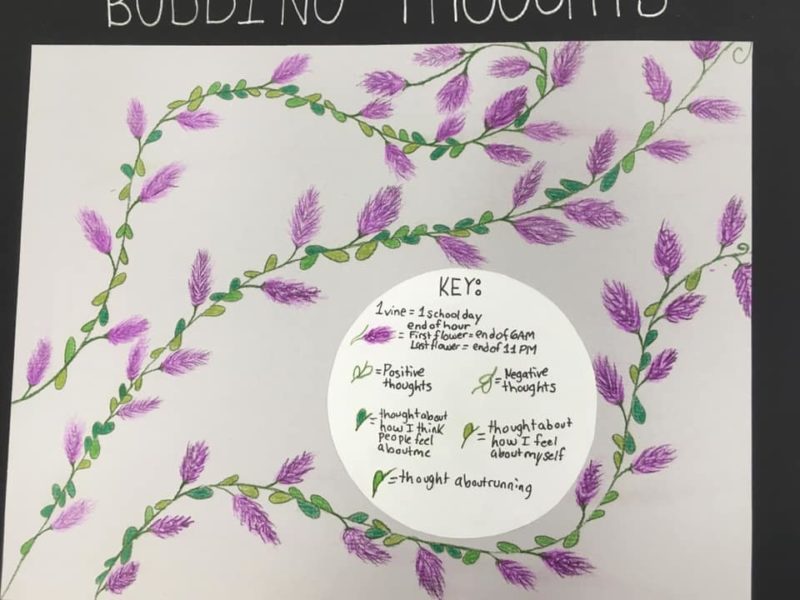

As I got a little more comfortable working with Big Questions I decided to turn the tables and have my students develop their own questions. I was inspired by Mark Dion’s Tate Thames Dig (1999) where he secured a space in the Tate Museum to display artifacts that he had not yet discovered on the banks of the Thames. I loved the idea of creating artwork based on questions, the idea that not even the artist knew what the outcome was going to be. I later found out that this was known as Inquiry Art, but at the time, it was a brand new concept to me. Through speaking with other teachers at a Curriculum Slam, at yet another Art21 Educators Summer Institute, I was introduced to several other inquiry-based projects and artists including the Dear-Data project (by collaborators Giorgia Lupi and Stefanie Posavec), the artist Lee Walton, and the sculptor Nathalie Miebach. I decided to challenge my students to ask a question, collect data, and create a visual artwork that presented the data. I gave them one week to develop a question, a data collection tool, and to collect the data. Then they had one more week to create the artwork and design a “key” that would allow viewers to interpret the work. Some students decided to keep journals and track personal information like mood swings, stress levels, and even the lies they tell. Other students wanted to collect data on things they noticed at school. One student interviewed others about emotionally safe and unsafe spaces around the school. One of my favorite projects came from a student who, even though she did her work, was constantly being scolded in a whole class setting because her classmates were not doing their homework. She decided that instead of complaining about her classmates, she would collect on their reasons for not completing work. She had assumed that the other students just didn’t care; through the project, though, she came to realize that the number one reason the work was not getting done was that students were often way overscheduled and had to pick which assignments they could complete. She now had the opportunity to present her findings to her teachers so that they could get a little more insight as to why students were not doing their homework, and potentially adjust their expectations and assignments.

IMAGE: Photo by Thomas Dareneau.

I find that, when working with Big Questions, each lesson becomes an individualized and unique experience for both students and teacher. When we ask questions rather than simply presenting material, it keeps our curriculum fresh — even if we use the same lessons year after year. Further, I have found a greater sense of purpose as an educator when I ask myself these Big Questions. I feel it’s easier to keep sight of our overall purpose and not get too bogged down in small day-to-day details. And the feedback has been very reassuring: I have received unsolicited positive emails and compliments from parents of non-traditional art students excited to talk about their student’s work. The incorporation of Big Questions into the classroom allows the creation of meaningful projects designed to engage all students of all skill levels.