Interview

German Brutality and Roman Sensuality—Pictures of Soldiers in the Landscape

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 2 episode, Loss & Desire. © Art21, Inc. 2003.

Collier Schorr discusses the symbolism of the Nazi uniform, and the power of the androgynous, ambiguous quality of her photographs.

ART21: How far off are the pictures you make from ordinary German family photographs? Say, of Herbert and his family’s photos?

SCHORR: It depends what you know. There are photographs not unlike the photographs I have taken in family albums of this family. So, there are pictures when the family lived in the German part of Romania. There are pictures of the uncle with three of his best friends when they were in the Romanian army in the ’60s. There are pictures of the father with his friends when he was in the Romanian army in the ’40s and ’50s. People whose family members served in the armed forces have pictures of army buddies hanging out. And I think those were some of the pictures that I was trying to remake.

ART21: Did you see the photographs first and then restage them?

SCHORR: It’s not that I had seen the pictures and said, “I’m going to remake them.” It’s that the pictures I make don’t always veer that far off from snapshots that guys who served in the army would bring home or send home. You know, “Here’s a picture of me in the trenches.” People don’t send home the pictures with their best friend’s head blown off or body on fire. They send home pictures of arms draped across shoulders, smiling for the hope, that one day you’re going to be home. And so, those are the kind of pictures that I was interested in making, and especially making them in Germany. Because for me, Germany has such a powerful military history.

Germany has such a hold when you’re a Jew and you walk around in Germany. And I wanted to not stand in its shoes, but to sort of see it from all sides. I always saw it from the side of the Jew who felt victimized, or the Jew who felt oppressed. And I was very comfortable in that role for many years. But by being in Germany for a longer amount of time, my experience changed and my relationship changed to the country. And my curiosity about what it was like from the other side opened me up.

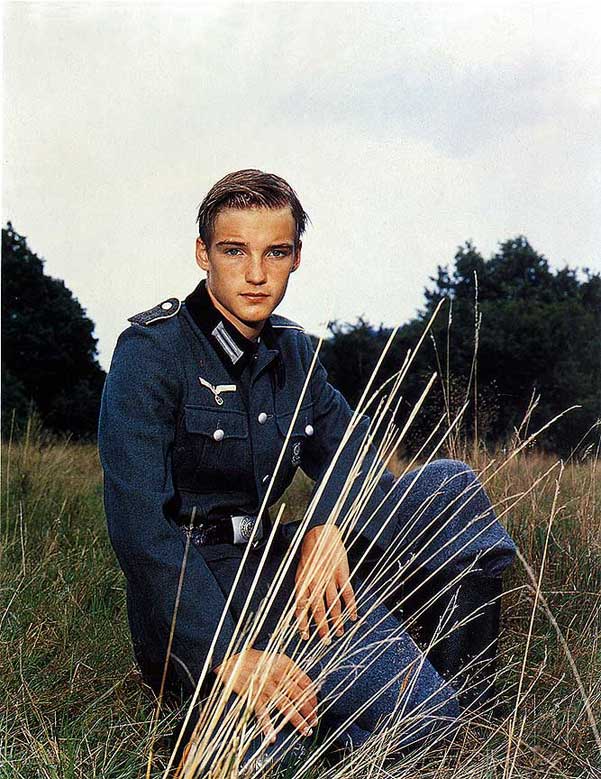

ART21: The Nazi uniform is such a powerful symbol in your work. Could you talk a little about the various uniforms?

SCHORR: The use of the uniform is really one of the reasons that my last show had three distinctly different uniforms: current German Bundeswehr uniforms, Wehrmacht Nazi uniforms, and Vietnam uniforms. I used three different kinds of uniforms to illustrate how these bodies fit or don’t fit into these clothes. Young guys have been lined up for centuries and outfitted. And some people fit into the uniforms and are soldiers, and some people don’t fit into the uniforms and aren’t soldiers. And some people pretend to be soldiers. And I wanted to show that political causes change, but soldiering is really consistent. And it’s really about putting young guys in scary places and asking them to die for someone else—asking them to die for a cause they might not understand. And I wanted to really talk about this history in Germany that is so often not talked about in Germany and so obsessively talked about by Jews.

The landscape is filled with relics and memories. So many things are buried in the landscape in Germany, so many uniforms and medals. And you hear stories of people coming upon buttons and helmets in the fields. I really wanted to flush some of that up, to dig some of that up, almost as if some of these soldiers seemed to have come up from the ground. So that, if you were walking in the field and you saw a helmet, it was as though the soldier rose up with that helmet. And he didn’t rise up as the ultimate villain, and he didn’t rise up as the ultimate victim; he rose up as just a guy who fought, just a guy who died, just a guy who killed someone.

I was interested in confronting that guy rather than confronting all the movies I had seen in Hebrew school and the books that I had read, like The Diary of Anne Frank. I needed something less extreme in order to unpack my relationship to Nazi Germany and my relationship as a Jew to the Holocaust. To separate it so that my definition of myself wasn’t due to a tragedy—that I wasn’t Jewish because of the Holocaust—that I wasn’t more Jewish, and that I wasn’t a certain kind of Jewish because this thing had occurred. It’s difficult to extricate yourself from that kind of drama or trauma. But it’s an interesting exercise. It’s interesting to try.

I was simultaneously interested in what it’s like to censor your own history—what it’s like to remove pictures from family albums—and what it’s like to not know what people did in the war. I’m so used to a culture where every story is retold, and where anyone who’s fought in a war is going to have war stories, except for Vietnam. And that’s why, for me, Vietnam was an interesting addition to the scenario because—not to say in any way that the guys who served in Vietnam were like Nazis or vice versa, or that the Vietnamese were like Jews—but that these were two groups of soldiers that came home to no parades. They came home to a repression of history. They came home to an erasure of an experience that they endured.

And so, I wanted to compare those two things and to think about how this country has changed its relationship to the Vietnam War over time, and how Germans are in a sense trying to accomplish the same thing. They’re trying to rescue their Wehrmacht from the SS. They’re trying to create a way in which someone’s grandfather’s picture can be in the photo album. It’s a difficult endeavor because it’s hard to know who’s really guilty, and who’s just a little guilty, and what you should be guilty of.

Collier Schorr. Andreas/POW (Every Good Soldier Was a Prisoner of War)/Germany, 2001. C-print; 39 × 28 1/2 inches. Edition of 5. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

ART21: What did the family think when you first started dressing the younger members in Nazi uniforms?

SCHORR: If I had dressed them up as Nazis the first year I arrived, I think it would have been problematic. But I’ve dressed them up as so many other soldiers that it was almost as though it wasn’t a surprise, as though I was working towards this the whole time. And I wouldn’t be able to visit with this family were their history such that I felt like it was a betrayal of my own history. I did investigations, and like any family, they had one or two guys that were in the SS, but nothing that close to this nuclear family. And they were in a German part of Romania during the war. And so, at the same time Jews were fleeing the Germans, they were fleeing the Russians and went on this huge march to Austria to escape. So, they had their own devastation to deal with.

I think that, when you take out a Nazi uniform in Germany, a couple things happen really quickly. People are scared and somewhat excited. It’s like this kind of forbidden thing. I remember unpacking the uniforms. And the grandmother of the family—I asked her, “Oh, does this shirt look like it’s from that time period?” Because I wasn’t sure if I was holding a reproduction or not. And she said, “Oh, I haven’t seen that since the ’40s.” And I said, “Well, there you go.” Clearly, these were things that she recognized from when she was, like, eight years old or nine years old.

I think they’re also very supportive of what I do. I think they trust that what I’m doing has a point beyond exhibitionism or shock. They see the pictures. I was struck when Herbert’s grandmother saw one of the pictures on my invitation card of Herbert in a Nazi infantry uniform, and she said, “Oh, I want a copy of that for the living room.” All she saw was her grandson dressed up as a soldier, and it reminded her, maybe, of something in childhood. And I think she felt that I had given her some kind of permission to look at that and not turn away. And that was interesting to me—scary, but interesting.

For me, there is no progress unless you put things forward, unless you unveil desire, unless you unveil repression. If you have a question, ask it. And that’s the exact opposite of life in Germany. So, when I’m in that family, I ask all the questions. People were shocked to find out that the family knew Jews, because no one asked. But I asked, “Well, how many Jews were there in your village? And what did they do? And what happened to them during the war?” And things like that.

ART21: Do you feel that you’re in some way exorcizing your own demons?

SCHORR: I think I’m creating a German soldier that I have control over. So much of my work—in terms of wrestling and sports, especially portraits of large, blond, strong guys—is really about confronting a sort of Aryan myth that terrified me as a little girl. I would read books like The Diary of Anne Frank and things like that. And that was what you were scared of; that was the Jewish girl’s boogeyman—you know, the big blond guy coming up the stairs. And so, I had been courting that, getting closer and closer to it, to find out if it’s really what I built it up to be. And to make it more accessible, somehow. It is about control. It’s about recreating a scenario that would have been extremely threatening, and emasculating it, in a sense.

ART21: How did the uniform project start?

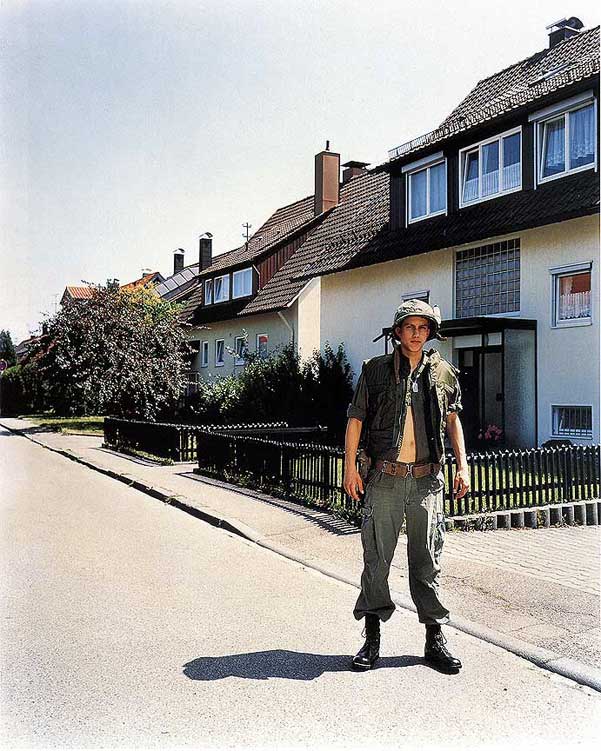

SCHORR: The first soldier pictures I took were of Herbert and his friends. They all collected army stuff, and they would go on campouts and play army and raid each other’s bunks. And I was really surprised to find that all the army stuff was American, and they were basically dressing up as Americans in a territory that was in fact occupied by American soldiers who were driving all over town in jeeps. And so I asked him, “Well, how come you’re dressing up as Americans?” And they said that that was what was available. But also, I think more importantly, that was what was cool or fun. It was cool gear and they were gear-oriented.

So, my first pictures were really to put the guys in their German landscape and have them play out this occupation that I was watching from afar, when I would drive by the army bases. As much as the Americans were present in the town, they were also very much in their barracks. And there were gates, so you couldn’t really access them. You might see them in town, but they were really kind of doing stuff in their own world that you would pass by. By dressing Herbert and the guys up, I was able to play out my own idea: to make it some kind of a strange little Mount Everest that they were conquering in the most lazy fashion.

So much of my work that has to do with war has to do with waiting for one. It has to do with the fact that it may never come—that you’re kind of preparing, almost leisurely, for something that might not happen. And that preparation is almost like organized sports. It’s almost like being on a football team or the wrestling team. It’s drills and practices and uniforms and camaraderie. And so, I just wanted to create for myself this presence. Not an army that was occupying from within its barracks, but an army that was really occupying the land.

Collier Schorr. Matthew/Occupation/Barbarossastrasse, 2001. C-print; 44 × 35 inches. Edition of 5. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

ART21: There’s an androgynous and, moreover, ambiguous quality to those pictures, of Herbert and his friends.

SCHORR: Well, I think when you shoot thirteen- or fourteen- or fifteen-year-olds, none of the boys have hair yet on their faces. Everyone’s very soft, and some guys are thin. Herbert was really thin, and another friend of his was really kind of curvaceous.

Gender, religion, nationality are all in flux in my work. They build on each other, on the idea that you’re not sure what you’re looking at, what you are, what someone else is. The avenues to desire are skewed. I wanted to make work that spoke to as many people’s desire as possible: maternal desire, fraternal desire, desire for romance, for youth . . .

I think also, particularly with the guy stuff, I wanted to be in a fraternity that I never was. When I take pictures of guys who are wrestling, or when I take pictures of guys who are dressed up as soldiers and running around, it’s not the feeling of when you watch basketball, and you see someone hit the basket, but it’s close. It’s like you’re running with them—you’re not, maybe, doing it—but you’re running with them, you know. My heart rate goes up. It’s like being in the center of something that’s so different than female friendship. For me, female friendship was always an intense thing. And boy friendship was always, like, “the more, the merrier”—you know, thirty guys packed in a basement room, listening to Black Sabbath and dancing, and not knowing who they’re even talking to—they’re just a bunch of guys.

I think I bring a certain fantasy to masculine adolescence. I don’t know for sure what it was like, but I’m interested in preserving or recreating moments from it. Because I think the pictures show a wider scale of emotional life for men. And particularly, the wrestling and army stuff is really about physical contact and danger and support. And so, I love when I’m shooting wrestling, particularly in practice—to see two guys throwing some moves and then being careful that they didn’t hurt each other. Pushing as hard as they can but then pulling back, making sure that they’re okay. Talking about it, talking about how to do it better, giving each other advice. All that kind of stuff, I think, is to me a rich part of masculinity that I think dissipates when guys get older. Because priorities change and, you know, they pair off, and they enter into a different world. But for me, it’s just this really interesting, rich place.

ART21: Could you talk a little about why it was so important to have the boys occupying territory out in the German landscape?

SCHORR: The Beckers, Gursky, Ruff, Struth—you can trace that sort of description of Germany to August Sander, who I would say was sort of the precursor of the Düsseldorf school of photography. There are Nazis in Sander’s book. I mean, his project was fascinating because it described everything, or so much of what was going on in Germany, including the Nazis and Jews and the gypsies. And I’ve always felt that the 1960s–80s Düsseldorf school chose sections of the Sander project.

And I think I set out to choose the sections of the Sander project they didn’t really choose—which is that I’ve taken pictures of Jews, and I’ve taken pictures of Nazis. I think that Düsseldorf approach to the landscape was very traditional. You can go to any flea market, and you can find old photos or old drawings of the German landscape. And they all look like Sander pictures of the landscape: just kind of beautiful, picturesque, slightly romantic, slightly vacant—there’s actually not a lot going on.

The thing with the Germans is: they love their land. They love pieces of their land to be uninhabited, and so they can relate to a photograph of nothingness in land in a way that I think Americans don’t. Maybe we have that with our pictures of prairies, but I don’t think it’s quite the same kind of obsession. So, when I look at some old German landscape pictures, they’re beautiful, but they’re nothing, because that’s how parts of the land are in Germany. They don’t have anything on them but nature. And I think that artists in the latter part of the last century were trying to keep to that traditional, cool, detached view of the landscape.

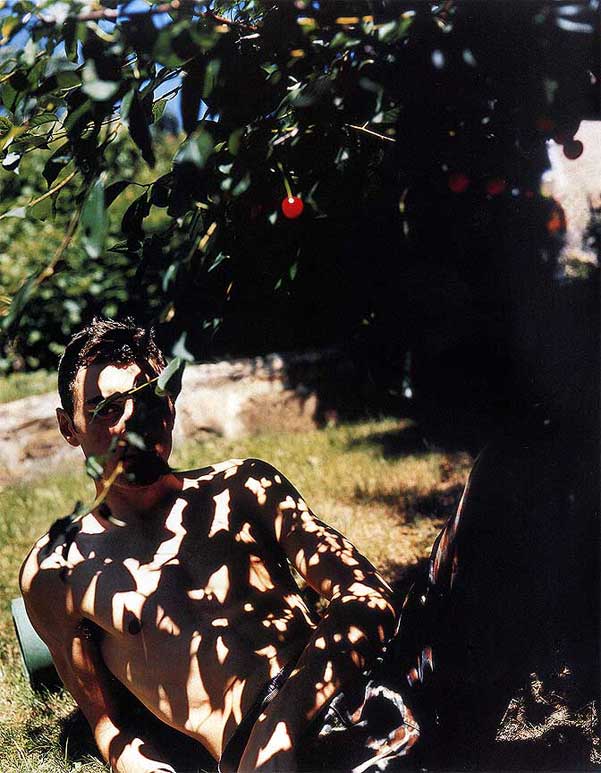

But I was interested in the tradition of photographing the landscape and finding a way to insert more tension into it. So that, if the tree, if the forest is the pride of Germany, then, you know, let’s talk about what actually happened in the forest rather than just showing the forest, rather than just showing the kind of family gathering. I wanted to bring to the surface a lot of what made it so important. What made it so important was the violence, was the defense of the land, was the sort of anti-Roman sensuality. If any artist has been influential to me, simply because of what I read about with one of his paintings, it would be Anselm Kiefer—reading about the battles that took place in the forest between the Romans and the Germans.

My work has always been about the battle between German brutality and Roman sensuality, and the fact that you can’t have cultivation without sensuality. When the Germans left the forest, they had to take on some of the ways of Roman life. I think it was around 900 AD or something. The conservation of land in Germany was actually started by the Nazis, as a way of protecting the monument that is the forest.

Collier Schorr. Herbert/Weekend Leave (A Conscript Rated T1)/Kirschbaum, 2001. C-print; 44 × 35 inches, Edition of 5. Courtesy of 303 Gallery, New York.

ART21: So, the forest is like a repository of the German soul?

SCHORR: Well, I think that’s where they draw their strength. They see that they came from this place. So many other cultures look away from their brutality and more towards their civilization. The Germans seemed very comfortable looking at their brutality and seeing that as a civilization. Seeing that kind of wholesome, woodsy life—that I don’t think was brutal as a sport, but I think was brutal in terms of survival. In a sense, there is a defense against modernity. There was a defense against sensuality and against femininity. Against poetry, in a way, and in favor of athletics and self-sufficiency and a kind of “pure living.”

ART21: It’s remarkable how much the past, even the ancient past, is latent in your work.

SCHORR: I started reading after I made the work because my agent told me about this Simon Shama book, Landscape and Memory. And I remember reading about the Nazis’s march into Italy, trying to find this codex and trying to reclaim this history of Arcadia.

I’m not making Leni Riefenstahl’s pictures, you know. I’m not making something that’s about the façade. I’m making something that’s about removing the security, removing the myth—and then, being left with something that is more human and more approachable.