Interview

On Photography

Carrie Mae Weems photographing a performer for her performance work, Grace Notes: Reflections for Now performed at the Sottile Theater in Charleston, South Carolina during Spoleto Festival USA. Production still from the Extended play film, Carrie Mae Weems: "Grace Notes: Reflections for Now." © Art21, Inc. 2016.

Speaking with Art21 founder Susan Sollins in New York City in August 2008, Carrie Mae Weems meditates on the photographers who influenced her work and how she constructs an image.

ART21: Who are the masters for you? Whose work did you look towards or revere, or still do revere?

WEEMS: I think my initial influences were the great photographers of the twentieth century, all those people who John Szarkowski [at MoMA] rolled out for us. We knew those people. I knew Garry Winogrand; he was a great dancer and could move you around the floor in a really terrific way. I knew and admired photographers like Tom Roma and Tod Papageorge; I thought their way of working was very interesting. But they were deeply chauvinistic; there were no women in the set.

Then there were the earlier ones, like Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans, who was a master. Evans and Robert Frank were two of the men I paid attention to because they understood something that I wanted to be close to: they had a way of approaching and describing the world that I deeply admired. I thought that Evans moved with a great deal of compassion, with his extraordinary vision for how to really define things, using the camera and light to describe and illuminate things in a specific way. I love that.

I think it was Roy DeCarava who really nailed it for me in this country: an American photographer who was working at the same moment and doing very much what Evans was doing. I realized that they were both working from a deep cultural resonance. Evans was using everything from zone 5 to zone 10, and DeCarava was using everything from zone 5 to zero. You had this incredible cool white of Evans and then these enormous and deep and rich blacks with DeCarava. They were both trying to define something that was culturally definitive and were moving through aesthetic territory—emotional, cultural, and visionary territory. I thought that was remarkable. I’ve always been interested in the fact that nobody else has talked about this, as a way of examining the different ways that photography took root in the United States, or in other places, for that matter.

How do we use light to describe the essence of ourselves? I think it was really an enormous idea. You can’t use the same light registry for African Americans that you do for White people. White people really do look better in zone 5 or 4; Black people really do look better in zone 5 or 6. It becomes very mechanical, in a way. There’s a wonderful book called In Praise Of Shadows, written by a Japanese photographer and designer. It has to do with the way in which light is culturally used; the way that a shaft of light falls into a room to illuminate the pot that’s sitting on the table is one aesthetic dimension and idea.

There is a German or Brechtian idea, in which the light is so brilliant, bright, hard, and brash that nothing can hide from it; nothing is escapable in that realm of light. Everything is there to be analyzed and examined. The light is telling you that. Those ideas and men—and they have been men for the most part—have been very interesting to me, and I think about them often. I think about the ways Brecht and DeCarava use light and the way that Beckett thinks about light.

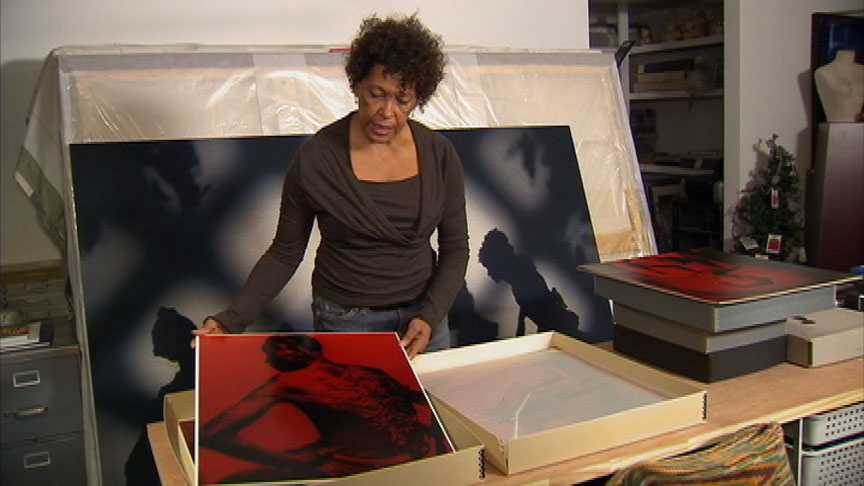

Carrie Mae Weems in her studio. Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 5 episode, Compassion. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

ART21: How do you think about light?

WEEMS: I’m swimming in a terrain that’s between two points of reference, between DeCarava and Evans. I think DeCarava was particularly interested in a description of African-American culture, but I don’t simply portray that culture.

My work is involved with other levels of description, ones that move across several categories; so maybe on the one hand I might be interested in what’s happening in issues of gender for men and women, Blacks and Whites and Asians, questions of globalism and class. It’s not just in the way that I engage the subject but also in the equipment that I use. I am more concerned with my old Rollei, my distance from the subject, and my way of constructing the frame than with the zone systems, which are more about breaking down race or color.

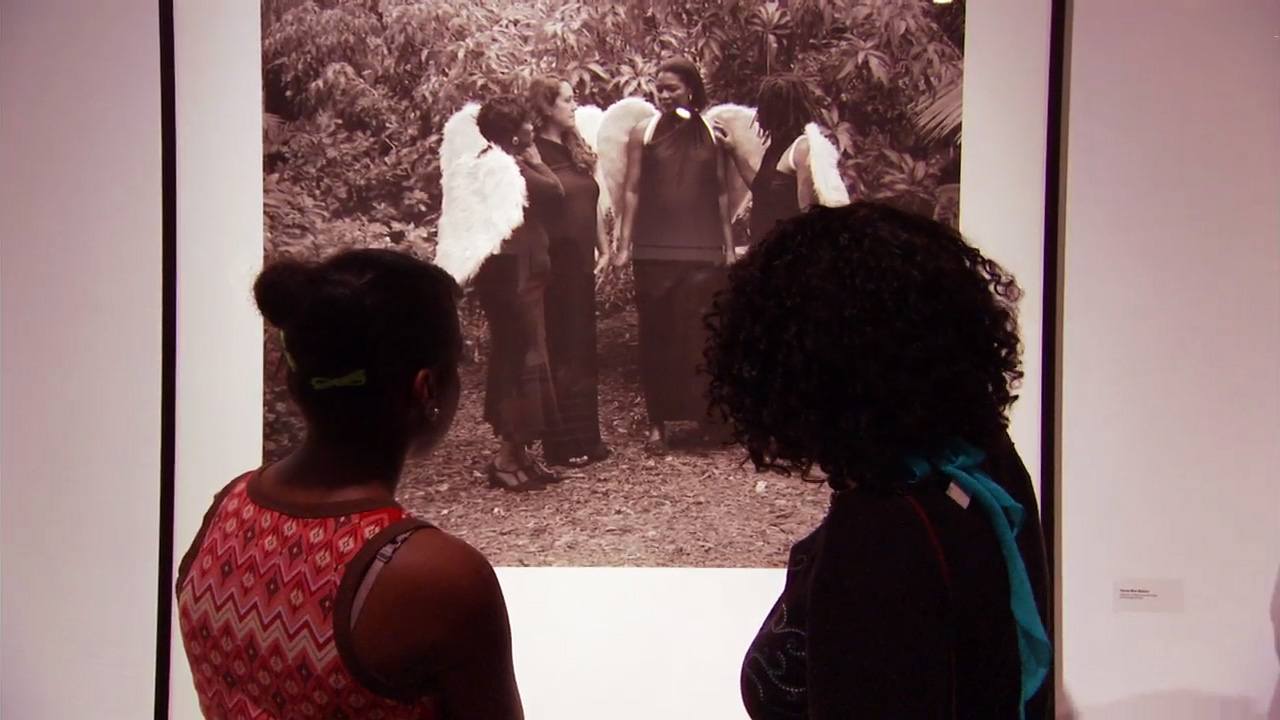

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 5 episode, Compassion. © Art21, Inc. 2009.

ART21: What are your thoughts about beauty?

WEEMS: I spend a great deal of time thinking about what something looks like. It concerns me deeply. I’m interested in how I enter the porthole, into the space of making the work: What does it need to have? What does it need to feel like? Conceptually, what is it trying to do? Even when I’m not completely sure of the answers, at least I’m starting with a weird set of ideas and questions about entering that porthole. I’m always aware of the fact that I need to take somebody with me, that I don’t want to experience any of this by myself, that the experience has to be shared. My way of sharing is to be as thoughtful as possible about how the work is constructed, so that the viewer will enter along with me.

I think the photographs are a contemplation of the sublime. I think that the work is also about confrontations of power. I have a sense that if there is a beauty and elegance that allows the viewer to be lost in the work for a moment, to be engaged with it, then the viewer will be more willing to enter the terrain and ask the difficult questions that are there. I think a certain level of grace allows for the entry. I work in a down-and-dirty way, yet my work is quite exquisite. The works are tender and nurtured and cared for, but doing the work is sort of rough. I’m usually traveling by myself; 95 percent of the time, I’m alone. I have a beautiful Hasselblad that I almost never use because I hate the way that it records the world. I use it only on occasion. I have a Leica that I use every once in a while, but I need a larger format. I’ve been working with this busted-up camera that I traded for a car in college. It has been everywhere with me; sometimes I sleep with it; I know it like the back of my hand. I love being alone and being out in the world and going into difficult places alone and confronting it by myself and doing whatever I need to do to get the photograph. I use a simple tripod and a simple camera and roll film.

I think about how beauty functions in the work and the idea of construction because my works are so highly constructed. My work called [Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment] makes that evident, using all of the tropes of construction to make the image. But all that stuff doesn’t get in the way of the heart of the subject; it simply frames where we are. The idea of framing, of course, is from the Renaissance. The frame was developed to carry all of the emblems of the profession of the person in the image: Is this a worker, a middle-class person, an authority figure, a pope? Who is this person? The frame tells us who that person is. In my works are wonderful points that could and should be explored. But because we are so profoundly troubled by race, my work has been stuck in the discourse about race for a long time. From this point on, any serious curators will have to take that to heart, or I don’t think I’d be interested in working with them.

This interview was originally published in the Art21 publication, Being an Artist.

Interview: Susan Sollins. Editor: Tina Kukielski. Curatorial and Editorial Assistant: Danielle Brock. Copy Editor: Deanna Lee. Published: September 2018. © Art21, Inc.