Teaching with Contemporary Art

Building Confidence and Community Through Rethinking Classroom Critiques

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

Picture this: You are the sole art education major in a class of fine arts majors. You sit nervously in a row, shoulder to shoulder with your classmates trying not to draw attention to yourself. You notice that a few of your classmates are suspiciously absent this evening. There is awkward silence as your professor paces back and forth in front of the critique wall. He stops in front of your drawing and takes a deep breath and turns to the class. In that moment, anything is possible, it could be victory or it could be utter defeat. Either way, you are pretty sure you’ve made a huge mistake in wanting to become an artist.

This scenario is how many Wednesday nights played out for me in college. These were our critique nights; I’m sure many of you have lived through similar experiences. Sometimes the professor did all the talking for hours; sometimes they encouraged participation, and on more than one occasion, they would set a student up and let the class eviscerate them. In my experience, although formal critiques were stressful and often unpredictable, they were nevertheless an important staple to most art programs. I firmly believe that critiques are essential to learning and growth. Students need feedback; they need comparison, and they need to see how other students approach solving problems. At the same time, I do feel that the traditional approach is somewhat problematic. I found they could be nerve-wracking, tedious, time consuming, competitive, and sometimes not very helpful at all. On many occasions, I felt like the process of critiquing classwork was more of an exercise in thinning out the herd than a real genuine opportunity for improvement. This was not the experience I wanted to give to my high school drawing and AP students.

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

I’d love to say that as a young teacher I learned my lesson and didn’t subject my students to what I’ll refer to as the formal critique process, but I would not be telling the truth. We often teach what we are familiar with and what was modeled for us. I participated in formal critiques as a student and then I gave them as a teacher. I didn’t initially consider how this might not be the best way to achieve what I wanted my critiques to accomplish. I wanted my critiques to be engaging; I wanted them to be useful; I wanted every student to feel comfortable in contributing to the discussion, no matter the skill level; I wanted (needed) them to be time efficient; I wanted kids to be able to immediately get back to work while all the suggestions were still fresh; and lastly, I wanted critiques to be a positive experience. I was hoping to find a format that students enjoyed and might actually look forward to. Once I realized that there wasn’t a one size fits all solution, I began to curate a group of activities that would fulfill the experiences I wanted for my students.

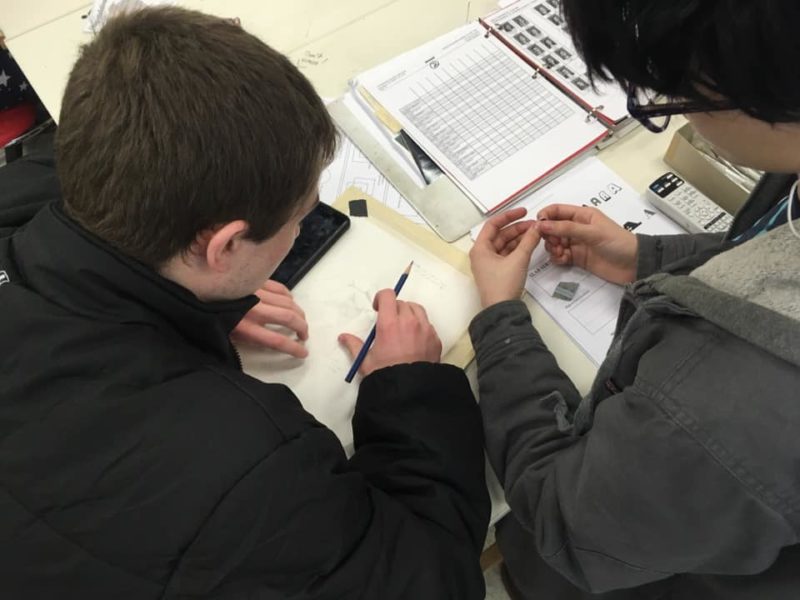

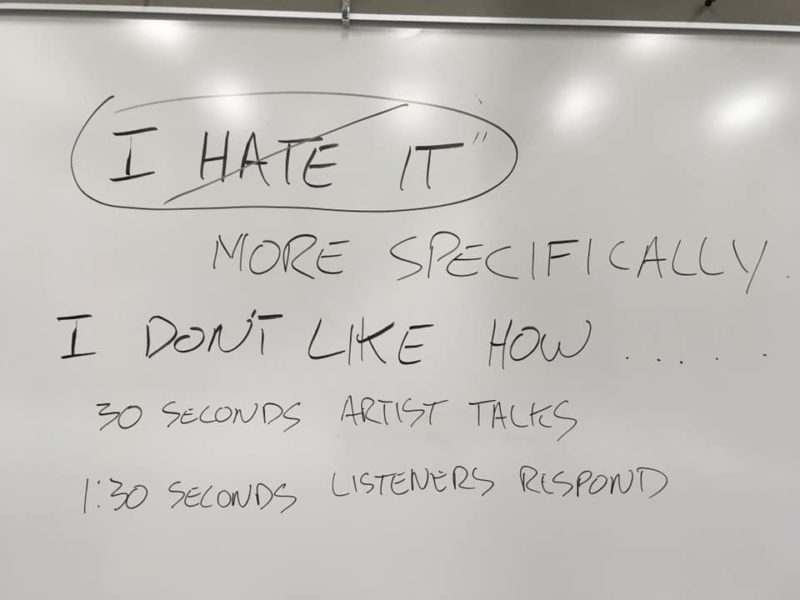

To relieve some of the pressure, I do most of my classroom critiques in small groups with a specific purpose and a very short time limit. I will break a class into small groups, and each group has no more than four students. On the board I will write a sort of rough script. For example — “You have one minute to identify any questions or concerns you may have about your own work. Your teammates will have two minutes to respond.” I borrowed the timing idea from Joe Fusaro and Jess Hamlin during a session they led at the 2016 Art21 Educators Summer Institute. With the use of smaller groups, students are more engaged without feeling the pressure of performing for the whole class. When given a script, some students felt more comfortable because there was a specific purpose and objective. Without a script, some students feel lost and unsure of how to contribute. By setting a timer and keeping the conversations short, students get right to business. I find that these short scripted critiques are less threatening than formal critiques, they take very little time, and all students are actively participating and receiving direct feedback.

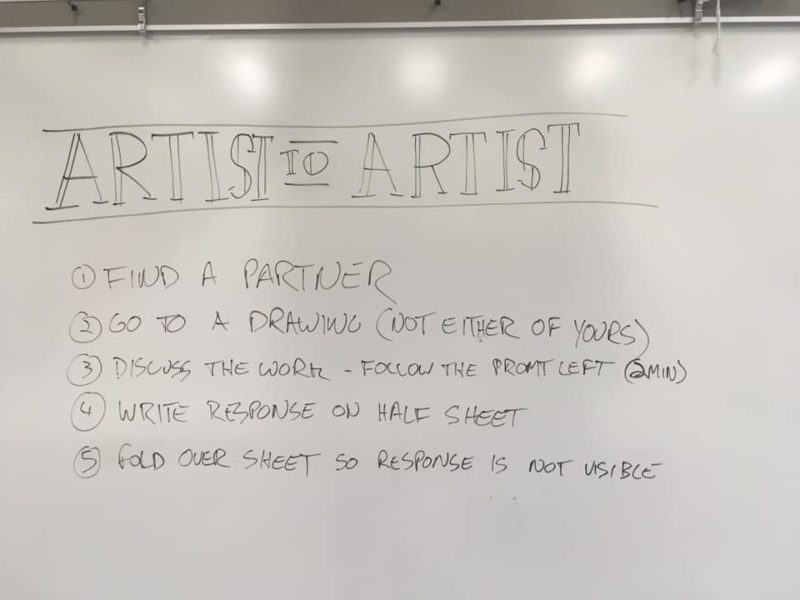

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

One of my favorite critique activities is an idea that I appropriated from a 2013 episode of the Art21 film series Artist to Artist. In the film, artist Diana Al-Hadid visited the 55th Venice Biennale. Al-Hadid has very intense and personal conversations with artists about their work at the Biennale. In one very short clip, she is talking to a friend about an artist who isn’t present. One of my objectives in holding critiques was to get students to contribute and speak more freely. I realized that Al-Hadid could speak more openly about the work when the artist was not present. She could pose questions, formulate her own interpretations, and have an opinion without the pressure of interacting with the artist. I decided to pair up students and have them look at the classwork. The only rule was that they were not allowed to look at their own work. My hope was that the pair would feel more free to discuss the work without fear of offending anyone. I was also hoping they would focus more on the process and not the artist. As a general rule, I do not allow my students to put their names on the front of the work so that during critiques, the artists remain anonymous. I try to move around the room and eavesdrop on some of the conversations. I often hear students guess what they think the artist’s intent was. The pair tries to identify what areas of the drawing are most important and how the artist is trying to draw the viewer’s attention. Sometimes the students discuss what the next steps should be and sometimes they just identify areas that were done well and areas that need more revision. Every so often, I’ll have them leave notes for the artist. Usually, though, I’m more interested in them just having an open discussion about the work than providing feedback. I was very excited by the students’ engagement with one another, but all of the critiques and discussions were very serious. I was hoping to find one or two ideas that centered around having fun and being creative.

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

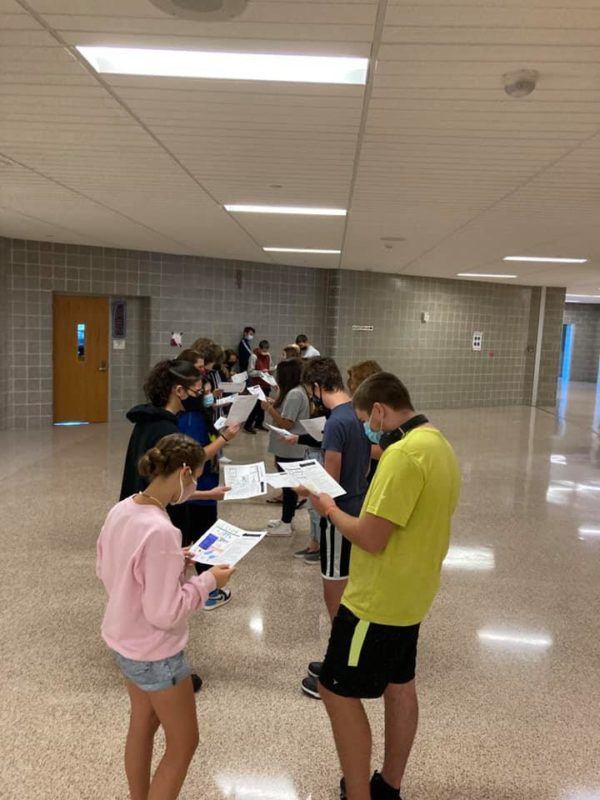

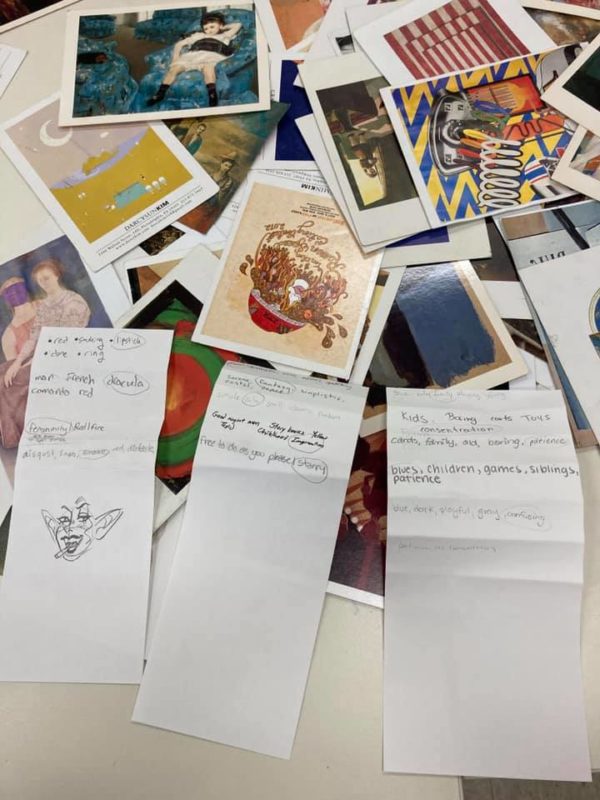

During Art21’s Creative Chemistries Event in February of 2015, I attended a session with artist Mark Dion and educator Don Ball. They showed us several collaborative art based games that could be played using postcards. They had the participants lay a blank piece of paper next to a postcard. Participants then moved to another seat and had 30 seconds to look at the post card and write the first five words that came to mind side by side across the top of the paper. The words could be descriptors like “red” or “frantic.” We were also encouraged to write down more personal words; for example, if the image sparked a memory we could write words associated with those memories. The next step was to fold the list of words under the paper so they would no longer be visible. We then moved to another seat with another postcard and repeated the process. We continued this sequence several times. Eventually, we all returned to our original seats and unfolded the paper, revealing all the lists people made based on our postcard images. Once we read all the lists, we were asked to circle one from each folded grouping. We were then tasked to take all the circled words and create something new. It could be a poem, a title, a lyric, and so on — one group member even started a drawing based on the circled words. Ball and Dion’s activity had us curating other people’s thoughts and then assimilating them into something new and unexpected. I thought this would be a brilliant activity for critiques, but instead of using postcards, I could use student work. Through this exercise the class gets to spend real time looking at each other’s work. It gives the critics the opportunity to look beyond skill and focus on first impressions and personal connections. I like using this critique as a collaborative way to wrap up a lesson. I find it to be a fun and low pressure experience where everyone contributes and everyone gets to see what ideas their artwork conjures up amongst their classmates.

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

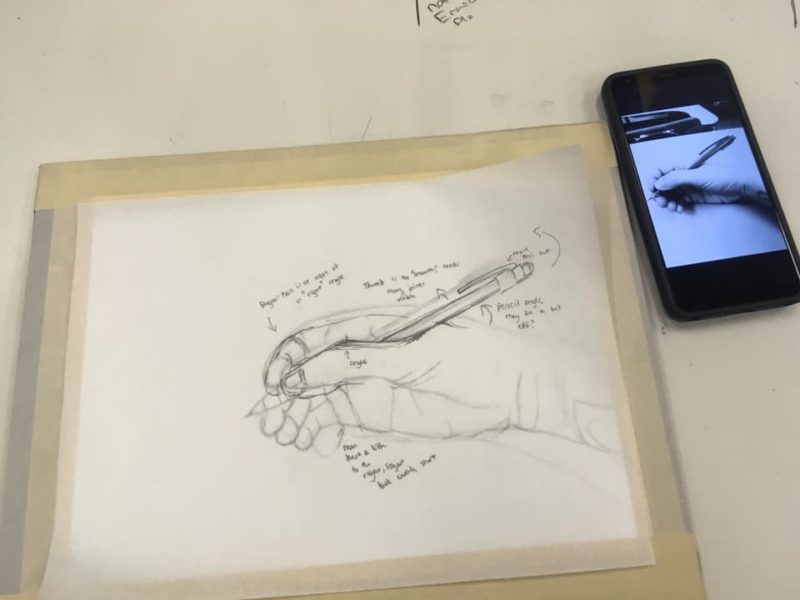

I love critiques that focus on concepts and emotions, but often in the classroom, we have to focus on very specific skills and techniques. When we worked on still-life drawings, students required one on one instruction. With my large classes, it was not possible for me to give each student the time required. I thought back to a collaboration activity that I was introduced to as a student at Kutztown University. One student would start their own drawing then the class switched seats and everyone continued working on another student’s piece. Even as a college student, I found this to be rather intimidating. There was always the fear of messing up someone else’s work. To make this less stressful and to put more of a focus on the process for my students, I’ll have them cover their work with tracing paper before we begin the critique. Instead of having them continue the drawing, I have them look at what has already been done and ask them to make corrections by drawing on top or leave helpful comments. By allowing students to leave notes as well as redraw sections, students who feel like they have weaker skills can still participate and give valuable feedback. Written feedback could be very specific like “this ball is too large” and “this area needs more contrast,” or comments can be more general like “something in this area is off.” At first, this is still intimidating for some students. I try to explain that all you are doing is making a suggestion that the artist can choose to use or choose to ignore. This explanation seemed to alleviate some of the tension. If time permitted, I had the artist and the critic review each other’s notes and corrections together. This way, they could discuss their findings and weigh their options.

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

Although I mostly use small groups and more collaborative forms of critiques, I occasionally still use the formal model of posting everyone’s work on the wall. The difference between what I do now and what I went through as a student is the intended audience and the intent. When I do formal critiques now, I am the intended audience. I am using it as an opportunity to see where the class is as a whole. I can then use that information to figure out the best strategies for instruction. Although I am the intended audience I still ask the class questions. I’ll ask the class to identify works that are exemplary in very specific areas. Instead of looking for problems, like we did in college, I ask them to identify positive examples of technique. When we look for specific examples of good techniques, it creates the opportunity for students to find something positive in every student’s work. By focusing on only positive aspects of the work, I find that students are much less intimidated and have a more enjoyable experience than I had as a student. I like to keep the formal critiques to less than 10 minutes, because I feel it’s important to try to get them back to the studio while there is momentum.

Photo by Thomas Dareneau

Moving away from formal critiques and using a multitude of different approaches has allowed me to achieve my goals for critiques. I am able to make them much less time consuming with more student engagement. I am able to focus student’s attention by giving specific tasks which makes the conversations more purposeful. Most importantly, I noticed a real change in students’ demeanor on critique days. Students show a new sense of confidence. They seem to be more willing to offer and seek advice. Their conversations often extend beyond the allotted time and they keep working together even after they were allowed to return to the studio. It is not uncommon for students to ask when the next critique is going to be because they desired the class’s feedback. I found that when I moved away from formal critiques and implemented multiple approaches to the critical process, my students reported a sense of trust and support, rather than experiencing the competition and the anxiety I felt as an art student. Probably the biggest indication of success was when I found out that my Advanced Drawing and AP students secretly set up an Instagram account so they could critique each other’s work without me. Apparently, they grew so accustomed to working with each other that they didn’t want to wait for the classroom critiques to get feedback! For them, critiques just became a natural process — an opportunity to grow as artists.