Interview conducted for Art21 in January of 2024 by Jurrell Lewis. Original photography for Art21 by Timothy O’Connell. All other photography courtesy the artist, James Cohan, New York, Anat Ebgi, Los Angeles, and The Third Line, Dubai.

Big Question

How did you arrive at being an artist?

Jordan Nassar shares his path to becoming an artist.

Interview by Jurrell Lewis

I was living in Berlin and working at a small gallery, which began my engagement with the art world. It was my education about contemporary art as well as art history. I would go to different openings and learn about artists and their references. I would read press texts and take the time to look stuff up to figure out what they were talking about and learn a bit of art history that way. That was my art school in a sense. Having worked with so many artists in those years, seeing their studios, seeing their practices, and being the one who’s supposed to translate their ideas into a press text. I learned how an artist starts with an idea and ends up with an artwork. After six years of that, I started making work.

My work being Palestinian embroidery is connected to the fact that when I started making work, I was dating someone Israeli who is now my husband, and I started to go to Israel with him. I had been to Palestine when I was a teenager but hadn’t gone back as an adult. The entire topic was very stressful for me growing up in a Palestinian-American household in New York, where my surroundings were pro-Israel, but my dad was pro-Palestine. We’re Palestinian, and my dad was a doctor who had worked in Palestine. As a kid, I thought his perspective was very extreme but as an adult, I realized that he saw a lot with his own eyes and was trying to help people, but the way that he spoke about it sounded extreme when you’re inundated by pro-Israel views.

When I started dating my husband, I went to Israel with him and that was the first time that I spent time there as an adult and started to understand what it’s like there. I also visited the West Bank and saw friends and distant family who still live there and experienced what that was like. Engaging with Palestinian craft was a way for me to start thinking about how it is that I’m Palestinian, what that means to me, to my identity, and to my experience being a Palestinian member of the diaspora in America, not having been raised there. I was learning about craft traditions, the history of Palestine, all the different patterns in Palestinian embroidery, and the geolocations of the patterns. Connecting with this craft tradition opened all of that for me.

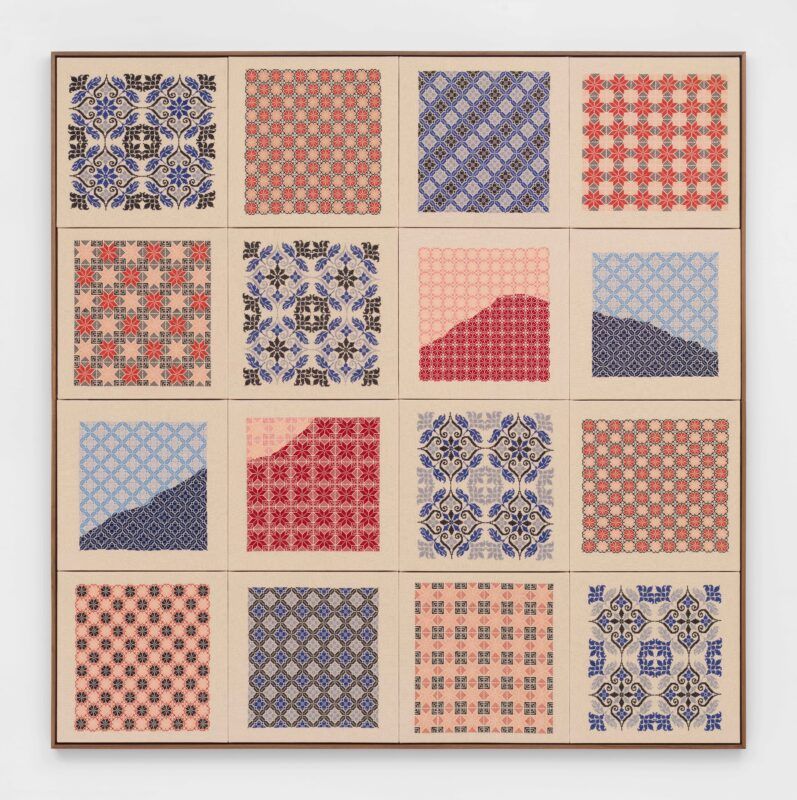

When I started working with Palestinian embroidery, I was very focused on the fact that each symbol has a history in a specific place. By looking at a woman’s dress, you could know which village she’s from. I was focusing on the language encapsulated in these traditional patterns and was fixated on the fact that I was not from there. I had moved back to New York where I am from, so in the first works I made, I started inventing a vocabulary of patterns that would be for a Palestinian from New York to use. All the patterns used in Palestine are based on different flora and fauna and geographical features from Palestine. I looked around my Upper West Side neighborhood and made symbols that were based on my surroundings. I was making compositions that mirrored Palestinian embroidery compositions but using my own symbols for New York.

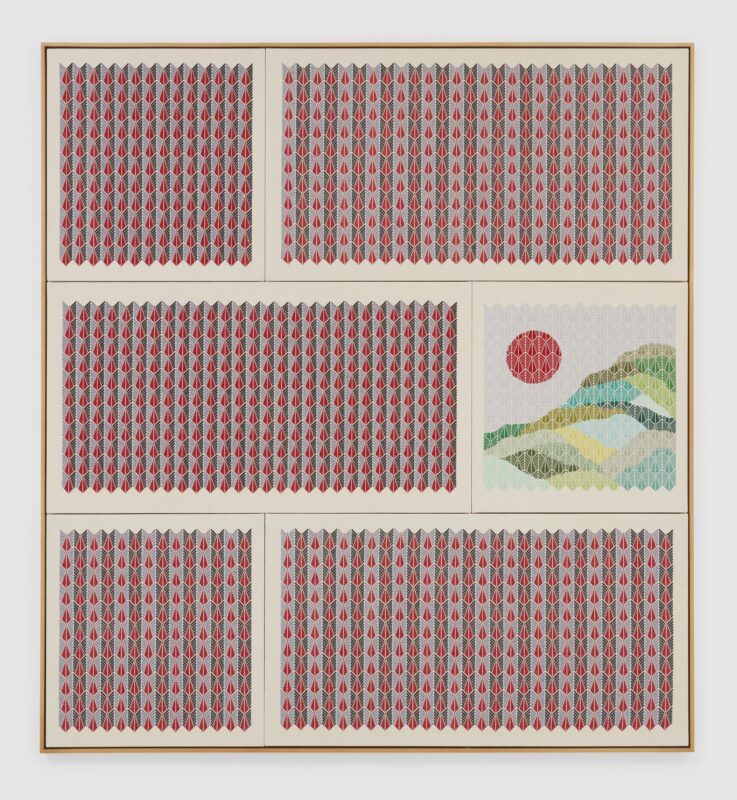

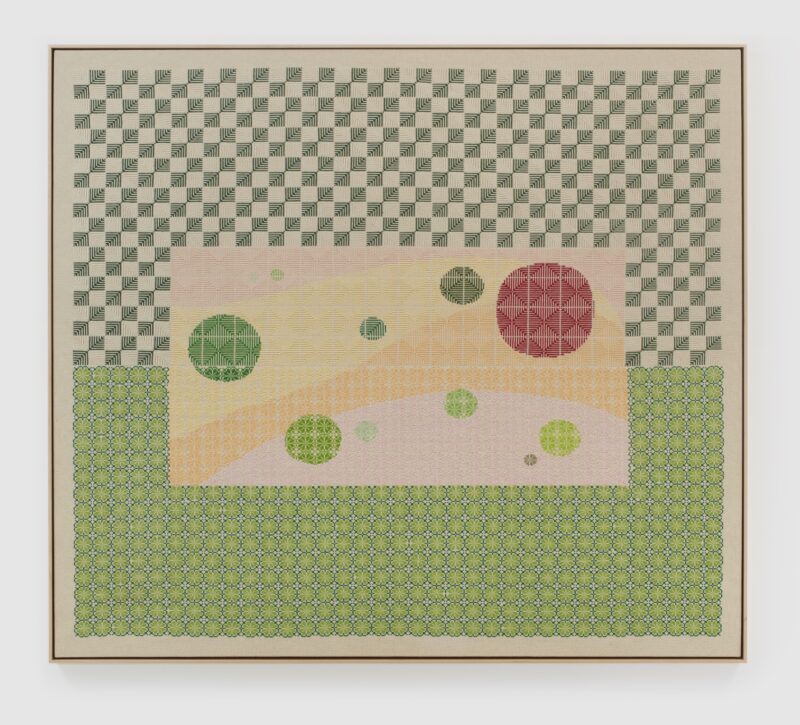

Over time, I came across Etel Adnan’s paintings, but it was her writing and the way that her writing paired with her landscapes, the poetic transfer, that got me to start making landscapes. Her paintings became so much more impactful for me knowing where she’s coming from through her writing. The first embroidered landscape I ever made was the only time I’ve copied a composition. I had the idea, “What if I could make a landscape through embroidery?” and at that moment, I needed just any landscape to try. I grabbed an image of this painting of Adnan’s and sketched it over a pattern I had and tried to see if I could do it. After making that piece, I told myself that I would not look at her paintings anymore because I knew I wanted to develop my own visual style. I didn’t want to just do embroidered versions of her paintings, so no more looking at Adnan for a few years.

I was starting to play with shapes and compositions, and like many artists, I was making work in the nights and on weekends. One day, a gallerist saw something I made and wanted to know more about it, and I ended up being included in a group show and showing my work more regularly. Then, I had a solo exhibition, and things started snowballing. I didn’t wake up one day and think, I’m going to be an artist as my job. You can go to art school or not, you can have your master’s or not, you can be making great work, and you can be really dedicated to doing it. All these things are variables, but at some point, you need to be in the right place at the right time and have someone want to give you that opportunity to try it. I don’t want to discredit all the work people do, being an artist takes a lot of hard work, but you need a break too. And when someone gives you the opportunity to do a show, you need to put on a great show.

When I had my first exhibition, the colors ended up being quite fantastical: purple skies, pink mountains, green moons. There was this idea of Palestinians in the diaspora fantasizing about this place that could look like anything. That became a larger idea for me. It’s not just my experience, but it’s a common experience. The way that my work engages with craft is through my personal lens. It’s Palestinian craft because I’m Palestinian. What I talk about is universal: this longing for a homeland or this longing for these connections to these places. These images hopefully communicate that longing for the place and this fantasy, which can apply to anyone from whatever background you are.

What has been happening in Palestine for over 110 days bears mentioning. I’m horrified by Israel’s relentless bombardment of Gaza. The impact on the millions of innocent people there, including my own friends and loved ones, who are without food, water, electricity, shelter, medicine, and other basic needs, is unfathomable. I hope every day for a ceasefire, an end to the occupation, and for freedom and safety for all Palestinians and Israelis.