Interview

Art Beyond Appearance

David Brooks in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Production still from the New York Close Up film, "David Brooks Hits the Pavement." © Art21, Inc. 2017.

Artist David Brooks describes how his experience with artifacts from Papua New Guinea inspired a newfound understanding of art objects existing beyond an aesthetic experience, with the potential to connect to functional, real-world elements. Brooks first encountered these artifacts in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art when he came to New York from Indiana in the 1995 to attend college at the Cooper Union.

ART21: How do you see Oceanic artworks differing from what’s traditionally valued by museums?

DAVID BROOKS: There was the life around the artwork while it was being made, there was the life around the artwork in how it functioned in the society that created it, and there was a life around the artwork in terms of how it got to the United States and inside the building of the Metropolitan Museum. These lives were so potent, and arguably more potent than just the way the artwork looked. And so that was a big moment of enlightenment for me—an epiphany—where what something looks like is not necessarily what it is, and not necessarily the most powerful or charged aspect of it. It’s the life behind it and the truth content within it, that is actually really quite extraordinary and goes far beyond just the way something appears. And so that was what became quite interesting.

ART21: Before that point, you just saw art as art objects?

BROOKS: I think like a lot of people that would’ve been at my age and time, there’s a certain way that art history is taught, in that it follows a certain idea of a canon. And for me that canon—the Western canon—hadn’t necessarily become interwoven with actual living. It was representing certain notions of life, and maybe it would have a certain impact the way that propaganda might have an impact, but the idea of living with something and it affecting daily life and affecting social dynamics was something I didn’t even have the capability of comprehending yet. I was just conditioned to think in terms of representational work that existed—like art existed only at the museum. So I better make sure I’m there when it opens so I can get my art experience, because when I leave I no longer get to have an art experience. That was just how I was kind of conditioned.

David Brooks, freshman year at the Cooper Union, 1995.

But to think about an art object as being so completely intertwined with a certain cosmos of thinking—about something that existed outside of one’s own lifespan—was enlightening. So to think of say, the ancestral totems that are at the Met in the Rockefeller Collection there, each one of those faces is an actual person. That’s the countenance of a real living human being, or one that was living, and through the representation of them, and then through the kinds of actions that were taken with the totems, that ancestor remains in living form in some sense. And so they are still performing a kind of function in society. They were not meant to just be looked at, but are representing an actual social dynamic in the moment.

Same with the canoes that were there, where you could read them as a sequence of not only spirits but real individual people. And you could read them almost like a family tree. So what might appear to my eyes, a Western set of eyes, like just a generic set of faces carved out of wood, in fact, are extraordinarily specific faces of individuals. And so that aspect of it being not just a portrait, but really embodying people, and then therefore the people that use those things being embodied viewers, was such an Earth-shattering moment of thinking about what the potential of an artwork can be.

ART21: So there’s the social history, and then the history of the object itself—that someone actually went out in the world and brought it back.

BROOKS: Yeah so there’s of course the original life of those objects, the one for which they were made within the Asmat culture. And then there’s the intervention, which is Michael Rockefeller at the remarkable age of 23, going to this region in New Guinea, and actually commissioning these people to produce some of these works for him. Which is a strange idea already, to commission works that have a function inside their society.

But I think to Michael Rockefeller’s credit, he understood these objects not as “primitive” and not as just something that looks interesting or peculiar in a collection—the way they might’ve been experienced beforehand, in what was then called the Museum of Primitive Art , which later became the collection that’s now at the Met. But he actually saw them as performing in society.

Detail of a totem sculpture from Papua New Guinea in the Arts of Africa, Oceania, and the Americas wing at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Production still from the New York Close Up digital series episode, “David Brooks Hits the Pavement.”

ART21: Can you connect that with some of your early projects, this idea that the artwork represents something more than what you’re looking at?

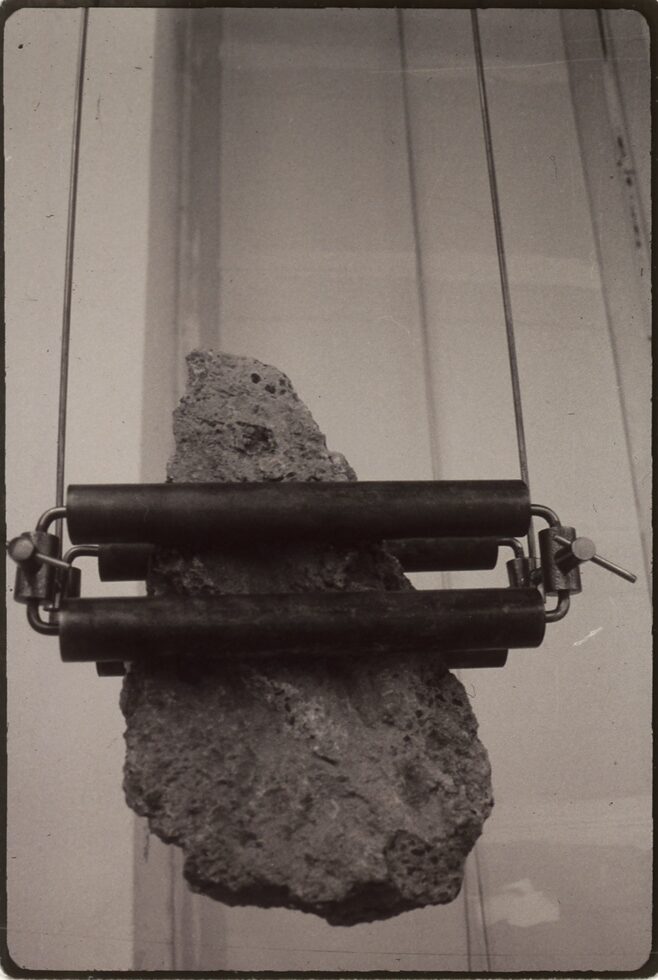

BROOKS: Yeah so there were various ways that I began to rethink how to make artwork, or just reevaluated what the making of work even meant for me. There was a project quite early on in my undergrad period where I had gone around New York City construction sites and actually gathered hulking pieces of asphalt that were jackhammered up out of the street. So I had a section of Third Avenue, Madison Avenue, the West Side Highway, Lexington, and St. Mark’s. And I had hung these slabs of concrete in these contraptions that I had machined, that were these kind of roller devices.

So a piece could slip out with gravity, but there was compression binding them together, so there’s that brutalist reality that brings back the objectness of them, and the qualities that those objects have, but mixed with this other life. And so the fact that one might glance at these and understand that they are Third Avenue, Lexington Avenue and so forth, is of course absurd. But it’s also a different way to think about the urban environment, and a different way to think about a bunch of gritty concrete hanging in front of your eyes, because they actually have this historical kind of truth content to them.

David Brooks. Five Suspended Pieces of Street (Hudson Street, detail), 1995. Asphalt, concrete, steel; 9 × 4 × 4 feet. Courtesy of the artist.

David Brooks. Five Suspended Pieces of Street (Madison Ave., 3rd Ave., Greenwich Ave., West St., Hudson St.), 1995. Asphalt, concrete, steel; 9 × 4 × 4 feet. Courtesy of the artist.

ART21: Does it also turn them into artifacts of our own time?

BROOKS: Yeah, they could be seen as evidence or artifacts of our culture, for sure, especially given the materiality of them. Because we are constantly repaving roads. The identity of what Third Avenue might mean will of course change over time, and so will the materiality of it. And so the idea that this is gonna represent Third Avenue or Lexington Avenue at one point in time, is very telling in a sense.

ART21: You also spent a ton of your life on concrete on a skateboard.

BROOKS: Yeah [LAUGHS] you could say I got to know concrete pretty well. It’s not a stretch to say there was an affinity between my own body and self, and concrete, and especially after years of skating and hitting the concrete—rethinking what a concrete shape can do in a performative way, but also often hitting that exact same thing when I would fall. Concrete took on a different relationship. I would call it an affection of sorts, or a deeper understanding of what it is, and the potential of it, and then what it becomes.

David Brooks frontside ollie in a full-pipe, Miami 2003. Production still from the New York Close Up digital series episode, “David Brooks Hits the Pavement.”

David Brooks skateboarding in front of the Metropolitan Museum. Production still from the New York Close Up digital series episode, “David Brooks Hits the Pavement.”

ART21: You were gonna tell me about another project?

BROOKS: A more recent project, the Repositioned Core that I did in 2014, which was a yearlong endeavor at the University of Texas at Austin. I was invited there to be an artist-in-residence, to come there and utilize the resources that are at UT at Austin, because it’s one of the country’s great research universities. And so typically, like a Northerner, when I think of Texas I think of oil, and so I wanted to find a different way to think about oil. So again, taking something that’s commonplace, or that we know or have preconceived ideas of, and trying to find a different way to understand it and think about it.

And in touring through the Jackson School of Geosciences at UT, I came across all these sculptural apparatuses, where people were making water flumes for studying how sedimentation would work—but water flumes the size of Olympic swimming pools. Or wind tunnels to study how sand dunes are formed on Mars. Really it’s kind of this sculptor’s playground, in a sense. But what was most breathtaking for me was when I went to the Austin Core Research Center, where they house 2.2 million rock cores—the largest repository of its kind in the world. These rock cores span the entire heyday of oil exploration , all the way up to today. The rock core is simply a section extracted from the earth, in order to study potential well sites. And these can range in size from two feet to 1,500 feet in length, and can be extracted from depths anywhere between 500 feet and 32,000 feet underground. The numbers and scales of this are so inhuman. And yet when you look at a rock core, it’s a very beautiful object, especially having a predilection for concrete and other types of rock forms. I have another kind of appreciation for what they are, but these have a whole history behind them. And in fact, the rock core I was able to work with, was from an area in Midland, Texas, which would be from the Precambrian area.

Archive within an Archive within an Archive (artist David Brooks walking the aisles of the Austin Core Research Center), 2014. Artist Project, Cabinet magazine. Photo: Gracelee Lawrence.

So these cores are considered extremely rare and priceless objects, because where these cores were extracted from, say in the 70s or 80s, there’s now entire housing communities and schools and hospitals, over these areas of the land. You can never go back and extract another core, because it would be illegal and dangerous. But you can frack it from five miles away if you know that there’s hydrocarbons in there. So these cores have a new kind of value now with new technology, if you find hydrocarbons that indicate there’s petroleum or natural gas.

To convince the Austin Core Research Center to let me use a core was next to impossible. But I did notice when looking through the many tens of thousands—no, millions of boxes—there’s a lot of them that had handwritten notations, like where the core came from and what depth they were taken from. So I figured there’s bound to be human error in there somewhere. I diplomatically persuaded them to search their database for conflicting numbers, and sure enough we found two rock cores that had conflicting coordinates. And because the data was inaccurate, they were worthless, scientifically, so I was able to have them.

Archive within an Archive within an Archive (drawer of rock cuttings extracted from a well in Midland, Texas in 1940, with a newspaper chronicling the early years of WWII being used as packing material), 2014. Artist Project, Cabinet magazine. Photo: Lily Brooks and James Scheuren.

Now one of these rock cores was in beautiful condition and very intact (they naturally break in sections) and was from exactly 5,285 feet down in the ground. It’s about 80 feet long, and would represent almost ten million years of evolutionary and rock sedimentary time. These rock cores can also cost nearly four million dollars to extract if they’re of exceptional lengths from really deep down in the ground. So these are scales of time, money and space that far exceed a human being’s understanding of conventional time and space and economics. And so knowing that—that this object is so charged with this backstory—but positioned in a particular kind of way in the gallery space, was a big part of it.

It was a simple presentation in a way, positioned on custom-made scaffolding that ran about 25 feet up into the ceiling, because it was a two story-high exhibition space, and came down at an angle—kind of like a transect through space. It would just nick the overhang of the architectural mezzanine, and then go down and pierce through the glass wall that led into the courtyard area of the museum, before returning back into the ground.

It was this idea of a line being very dynamic and active in a space, and actually interrupting the flow of people moving through it. It was a piece that had an activity to it—it was doing stuff in space, it was interacting with and interrupting the architecture, it was being returned back to the ground, it was piercing through the window. And it was moving between a microscopic perspective—where you can see the granular breakage and cracking, and even some of the shells and foraminifera fossils in it—and a macroscopic view at one glance, like up into the ceiling where you could barely make out what it is.

David Brooks. Repositioned Core, 2014. Rock core extracted from 5285 feet, metal scaffolding, modified architecture; 28 × 92 × 18 feet. Commissioned by the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

All of that, with the viewer knowing that this thing was 280 million years old and from exactly 5,285 feet down in the ground—trying to perceive this object from two different modes of your brain. This kind of factual didactic aspect, which is truth albeit a very inhuman reality of where it came from, and this other side which is very experiential and intervening on a very human world. It was the juxtaposition of these two ways of looking at the same thing, that for me was important for it, that it had this other life outside of just the way it appears.

David Brooks. Repositioned Core (detail illustrating view from mezzanine), 2014. Rock core extracted from 5285 feet, metal scaffolding, modified architecture; 28 × 92 × 18 feet. Commissioned by the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

David Brooks. Repositioned Core (detail showing fossilized foraminifera and other mineral veins), 2014. Rock core extracted from 5285 feet, metal scaffolding, modified architecture; 28 × 92 × 18 feet. Commissioned by the Visual Arts Center at the University of Texas at Austin.

ART21: How does this connect to your understanding of the Oceanic works at the Met?

BROOKS: Looking at this rock core, and thinking about it being 5,285 feet down in the ground or thinking about it being 280 million years old, which is very difficult to comprehend, not to mention the fact that it also came from an area that used to be a rainforest, and is now a desert. So knowing that, and using one’s imagination in combination with the hard reality of this tactile object that’s in front of you, was not too dissimilar from imagining the functioning of the objects I saw at the Met, where these objects from Papua New Guinea had a function in their society.

That’s not too dissimilar from how I was explaining the perception of these objects that had a whole life beyond what they appeared to be—in fact quite a depth of life that was extraordinary. You do have to use your imagination to see that, which is a form of projection of course, but you’re imagining while experiencing the thing itself. And so that combination of imagination with the experience of the thing itself, all sparked by a sense of reality, a verifiable kind of reality, is an amazing recipe for the relationship of things.

For more, see documentation of David Brooks’ Repositioned Core installation at the University of Texas at Austin, as well as see Archive within an Archive within an Archive, an essay by the artist and project featured in Cabinet magazine.