Interview

Underwater & Upside Down

Alejandro Almanza Pereda setting up a camera in his Hunter College studio (Manhattan, 12.21.15). Production still from the series Art21 New York Close Up. © Art21, Inc. 2015. Cinematography by Andrew Whitlatch.

Alejandro Almanza Pereda discusses the creation of “Everything but the kitchen sank,” his series of still lifes shot upside down and underwater in a DIY plywood aquarium.

ART21: Big picture—why are you doing this now?

PEREDA: I had an idea of this project back in 2007. I was in Mexico City at the time. I got a grant for making underwater sculpture from the National Fund for the Arts in Mexico. My idea was to just to kinda experiment with materials and objects underwater and to see how they behave and create these kind of structures. Like my older work, counterbalancing [objects], but in a different environment.

I don’t know why, but I’ve always [been] fascinated with those bubbles, that trap inside of spaces underwater. When you see a cup, you say, “Oh it’s an empty cup,” but it’s not empty—it has air, no? So when underwater, that air becomes content in a way. It’s interesting. So I bought a big tank and I just started putting stuff in it. Things behave so much differently underwater.

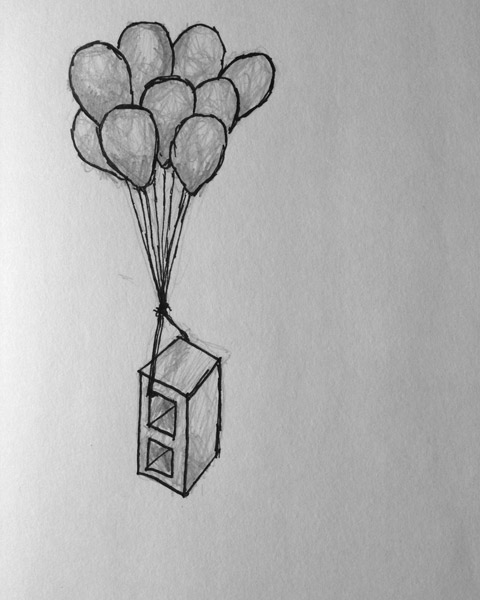

I started thinking about ideas for crazy pieces, you know, like two balloons tied to cinder blocks and those two balloons will then take the cinderblock up. I was [imagining] these crazy relationships with objects and situations. And I’d say, ok, I need to do it. I need to get in a pool, shoot it, or make a big tank and do it Damien Hirst-style with a sculpture inside. And I ended up going crazy about it.

I had not the slightest idea what I was doing. I just thought it was going to be easy but I spent all my money buying equipment that didn’t work: on scuba diving classes, on renting houses with pools that were not well maintained. They were not working or just [had] green water. And then, when finally I got into the pool trying to figure out things, it got really crazy. It’s really difficult to control things underwater. And it’s kind of tiring. It was such a catastrophe. I had a deadline to show my results. My computer got stolen, the camera got wet. I spent so much money and it’s funny, I only had like two or three pictures of that project.

Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

ART21: So how did it evolve into something usable?

PEREDA: I kept [the photographs] in the drawer. My friend Julio Morales [a curator at the Arizona State University Art Museum] came to my studio and looked at them. He’s like, “Hey show me your old stuff, your crazy stuff.” I just showed him the crazy funny picture of me underwater with a of pyramid of cups. It’s pretty strange, eerie. And he said, “What the hell is this?” I explained and he couldn’t understand [the objects were] upside down. He told me, “This is great, this is insane, you should do it.” So he invited me to go to Phoenix, with the help of the ASU Museum. So I went to Phoenix this summer, two times, because we had access to pools.

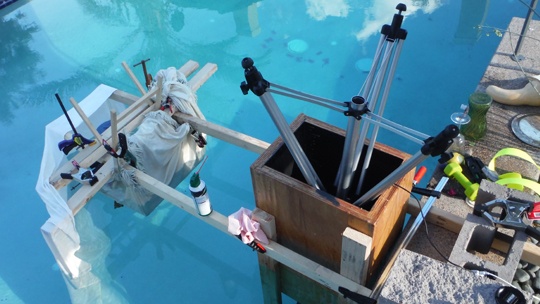

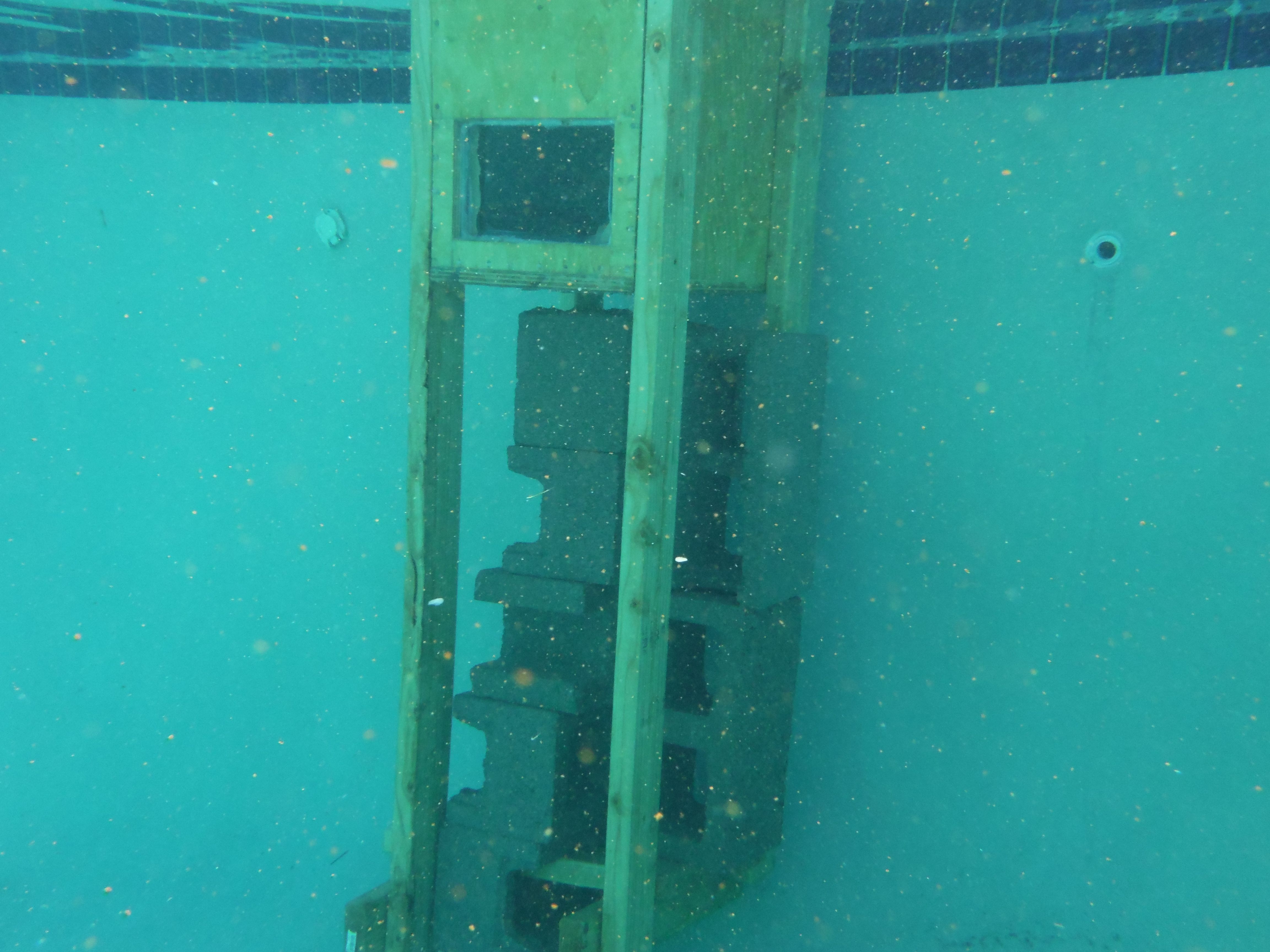

So I thought about all the problems I had before. [For the earlier project in Mexico] I had bought a housing for the camera. It was so difficult to be underwater and shooting. I didn’t have an air tank, so you need to go up and down. So this time it’s like no, I don’t need that. What I need is an empty space, a dry space in the pool. Instead of putting a housing on the camera, I built a empty space around the camera, so you can just have direct access to the camera. So you need to create this kind of submarine with a window. It’s a plywood box with resin around it, and the inside is black so you won’t have any reflections. You put it down with counterweights.

Drawing courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

ART21: What are some of the funny things you discovered?

PEREDA: So I had to get a lot of people to help me to drag it down, some people inside of the pool, some people on the surface. We had to buy like maybe fifteen cinder blocks to drag it down. [I put the camera in the box and] I bought this thing that connects to the camera and sends a signal to my iPad. So I can use my iPad to have full access to the camera controls, and I can see what’s going on. And in front, I put a table upside down. That’s the steady platform. But it’s upside down, so it’s like having a ceiling on the pool. If you put objects in the water, some float. And if they float and hit a solid surface, it will stay.

I have to say I’m not so crazy about being in the water. That’s the only problem. I don’t know why I wanted to be a marine biologist [when I was young]. Yeah I know how to swim. But it was always against my will, going to swimming classes, competitions. Just terrible, horrible experiences. Big amounts of water are kinda terrifying. It’s something you cannot control, you know. It’s nice to be grounded.

So Julio was there. He was thrilled to be in the pool. My friend Maira Monroy was there too. So those guys were in the pool having fun, and me I was having great fun [outside the pool.] I was with my cigar, my Hawaiian shirt, and just having beers. I was with my iPad. I was telling them, “OK now you put this here, no, again, action, no, again.” Such an amazing thing to be a director.

Alejandro Almanza Pereda. Better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all, video still, 2014. Courtesy of the artist.

Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

ART21: Why a still life underwater and not something else?

PEREDA: Well my first idea [was to] create this big sculpture, like my sculpture was a balancing act with furniture and things like that. But I needed a lot of equipment and help and infrastructure to do that kind of stuff. So I had to think about something that kind of resembles a sculpture in a way, and I had always been fascinated with the still life—that it’s just this arrangement of objects and materials that symbolizes a lot of things like passing time. And with this I can have more control, I can do it. With my first idea, to put the desk and and chairs and whatever underwater, that was going to be crazy. That’s going to be difficult. So let’s just start with [something] smaller, and so that’s my approach right now.

Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

ART21: There’s something really delicate and intimate about all of it.

PEREDA: I have to say it’s really nice to go back to a smaller scale. And make just a photo. It’s refreshing not to make a humongous thing.

My idea was to make really long shots of a vanitas or a still life. I learned apples float and pears don’t. It’s amazing. It’s like “whoa, the pear is just going down!” Grapes don’t float. And I understood that if I put in a fruit case made of metal and I put some fruits on that, [the fruits] will hold it. But I know that the fruit is gonna start kinda moving around and then suddenly, less fruit, less fruit, and that case is gonna flip. I was really interested in that. Heavy objects, they move really quick. Lighter objects, they’re super slow moving.

Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

ART21: What connection do you see between the still lifes and time?

PEREDA: It feels like there’s something going on, a narrative that you don’t get, but you feel kind of a little bit sad. How things go, disappear, or float. It’s dreamy, you know. It’s emotional and maybe it feels like memories. Memories are dreamy and are so different from the real thing that happened. Memories are always kinda cloudy. They are not so precise.

ASU Art Museum curator Julio Morales. Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

Photograph courtesy Alejandro Almanza Pereda.

ART21: Is it easier to take photos than to make sculptures?

PEREDA: Taking pictures is not easy. First I’m not a photographer and if a photographer’s sees my work [I’m sure] they would just immediately bash it, like smash it and think this is crap. I would love to learn more about technique, but I’m not so concerned about that because I kinda like the immediacy in a way. I don’t like ultra polished things. So I think I’m going to get better at it, but it’s not my intention. My intention is to make things, to document them.

Alejandro Almanza Pereda. Napa Uva, 2014. Ink jet on cotton paper print. Courtesy of the artist.