Amy Jackson joined Art21 Educators in 2021. She has been teaching art for 25 years in public and independent middle and upper schools. Since 2004, North Cross School, an independent college preparatory school in Roanoke, Virginia, has been her school home in various teaching and administrative capacities, but the art studio is her happy place. She is passionate about exploring, noticing, connecting, and reflecting as core components of making (and life!). As a perpetual learner who still wonders what she will be when she grows up, she gratefully credits Art21, and especially Art21Educators, with fostering her ongoing search.

Teaching with Contemporary Art

There is no finish line for creativity…

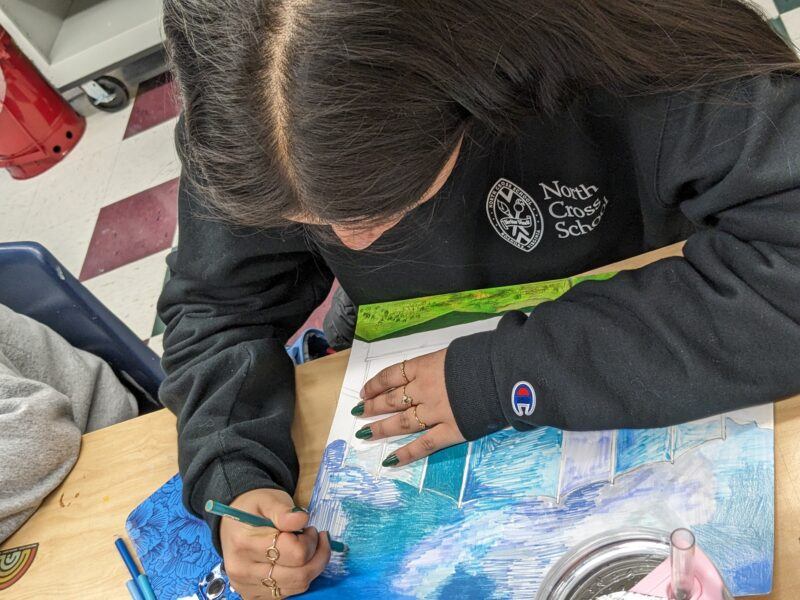

Courtesy of Amy Jackson.

“When will we stop working in this class?!” This was a repeated question by a spirited and talented but reluctant artist I taught a couple of years ago. He was just as incredulous, bordering on indignant, when my repeated response was, “On the last day of school.”

While we made a good-natured joke out of the ongoing exchange, it stuck with me that he—and many other students—saw our time together as finite boxes to check. If they could just get done with “the current class thing,” they could move on to “their things,” which they rarely saw as more art.

Courtesy of Amy Jackson.

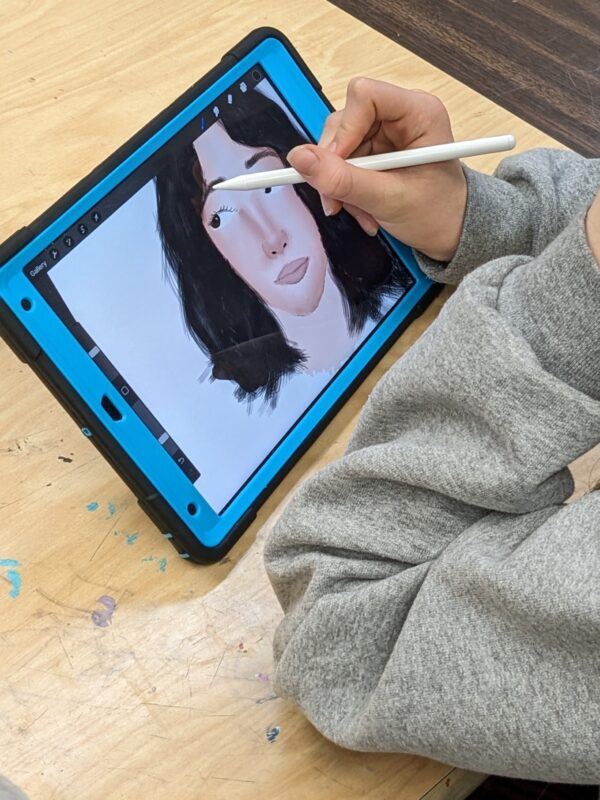

I desperately wanted to change that dynamic. While I tried to convey that every minute of our studio time together was precious, many were not buying it. I had already been moving toward a studio model for classroom operation to capitalize more on student voice and choice. After learning more about Teaching for Artistic Behavior (TAB) through some Art21 Educators, I was convinced that TAB’s guiding principles defining that “students are the artists,” “the classroom is the students’ studio,” and “students work like artists” were the next way I wanted to encourage my students’ ideas about making art. To push this further, I more specifically declared, “Students work like contemporary artists.” What better way to teach students how to be artists than by becoming familiar with artists working today and their current practices of making? I even have students repeat out loud in unison on one of the first days of school, “I am a contemporary artist.” The articulation becomes some combination of silly, contrived, and empowering, but the students seem to get it even if they are not all quite ready to own it. Pedagogically, these seemingly simple statements have marked one of the biggest shifts in my teaching career.

Courtesy of Amy Jackson.

Around the same time that year, a colleague shared a presentation that included an image of one of Nike’s iconic posters with the tagline, “There is no finish line.” Everything clicked into place for me with that image and sentence. The sports analogy turned what felt like my frustrating inability to convey the continuous and generative nature of creativity into a transferable connection. I was able to use the interests of students—from getting a personal record in swimming or track to a team nearly winning a championship to a student’s avid reading to one finally perfecting a song on the guitar—as a way to pose the questions, “Do you stop running after the PR, quit the team after the win or loss, give up reading or playing music after a particular finish?” Of course, students answered no, which begged the next question, “What do you do next?” To this question, the responses ranged from trying to best the PR, moving on to the next game, defending the championship, reading another book, and adding another song. Exactly. Art operates in the same way. I could see “a-ha’s” and grins on the faces looking back at me.

Courtesy of Amy Jackson.

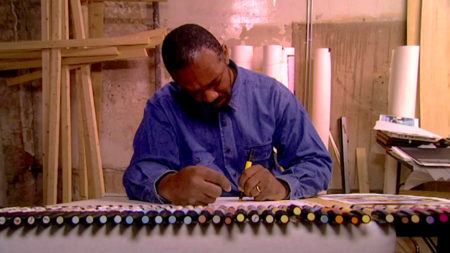

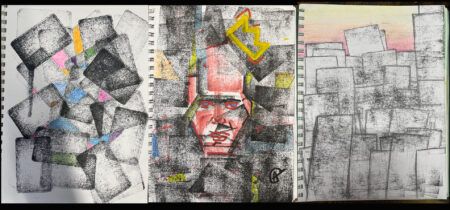

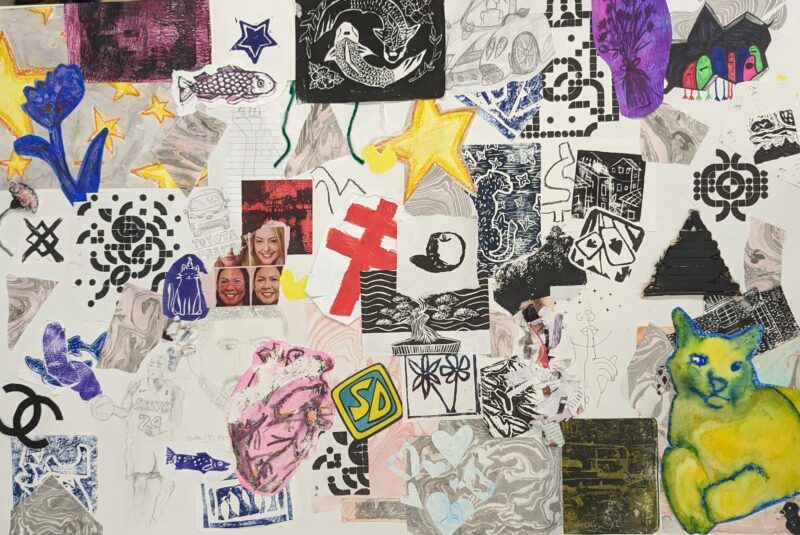

One artist we looked to for inspiration was Trenton Doyle Hancock, specifically a 2013 Extended Play film, “The Former and the Ladder or Ascension and a Cinchin.’” In the film, Hancock takes viewers through his studio and describes his artistic practice, specifically how he saves and uses detritus from previous projects in subsequent pieces that may form years later in new contexts. I wondered about all the student work that gets left behind or discarded. I set up a “collage station” and asked students to add a piece of their work they did not plan to keep to a large paper, considering the acting and reacting that would happen when people work on something collectively. I was not quite sure where the project would go; some students were more invested in “acting and reacting” than others. We could have continued to add layers, but on a whim, we cut the big piece into 6” x6” squares. Just cutting into smaller designs somehow transformed them into bits of beauty, but the pieces and the process still felt incomplete. I let each student pick a square to turn into something new again. The individual became a collective and then became individual again, but each square holds stories that shift from one to many and between random and purposeful. Through Hancock’s way of working and our varied experiments with process, students experienced an evolution of making.

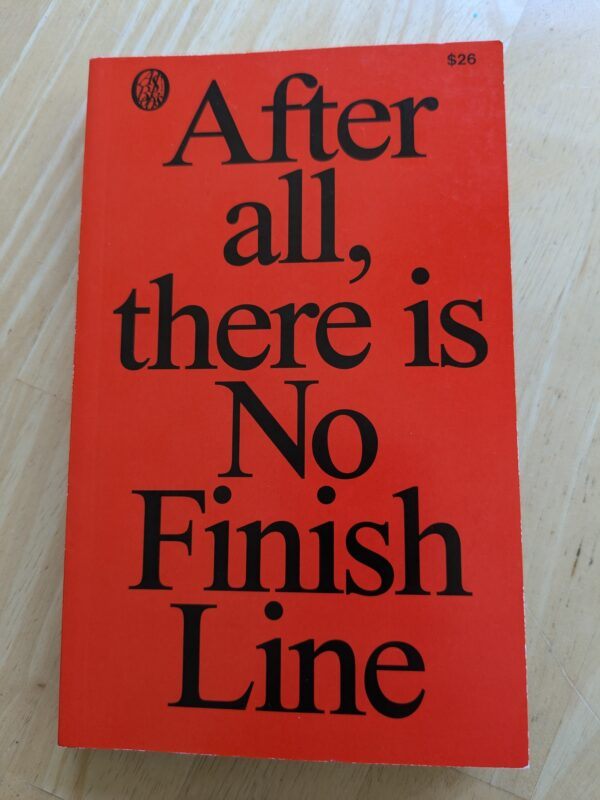

Grawe, Sam, et al. No Finish Line This Book Was Published in Nike’s 50th Year Editors: Sam Grawe, Jay Paavonpera, and Nick Schonberger ; Essays: Sam Grawe. Actual Source Books, 2022. Courtesy of Amy Jackson.

This intersection of contemporary art and Nike also must include Brian Jungen, who deconstructs and reconstructs Air Jordans. He describes “connections between the commodification of those shoes and the same thing that’s happened to Native Art.” Another resource in our studio is No Finish Line, a design manifesto of sorts published in Nike’s 50th year. It is filled with expanded parallels that can be drawn between the world of athletic shoe design, the grit of an athlete, and contemporary art. In the forward, John Hoke III, Nike’s Chief Design Officer, writes, “When we say, ‘There is no finish line,’ it’s not a lazy reference to an unending grind or destination-less journey, but rather an expression of our belief in the limitless potential of sport—and design.” These ideas from disparate sources began to form the studio I envisioned.

Courtesy of Amy Jackson.

The shared awareness of artistic practice, collaborative space, and perpetual creativity gave my students and me a pivotal understanding to fall back on. Our collective environment fundamentally changed with the studio (versus classroom) structure and the concept of “no finish line.” In the purest TAB studio, students choose ideas and materials based on their interests, which means everyone is doing something different at different times. On any given day, it looks like magic or chaos or magical chaos. It is often hard for students, especially those attuned to waiting on the teacher to give the instructions for when to start, what to do, how to do it, and when to stop. It can be hard for the teacher, too, trying to shepherd so many varying paths. Overall, though, the expectations in our studio are different, and you can sense it when you walk in the room. Students understand that when they complete one project, they start something else; when they have an idea, it begets another idea; when they have a question, more questions evolve; when they are creative, more creativity awaits them. They turn to each other and seek their own resources for assistance as often as they reach out to me. Overall, this simple sports-based slogan—“no finish line”—coached the artists in our shared studio to be more independent, persistent, resourceful, and resilient, and I hope this great creative adventure goes on for a long, long time.