Deep Focus

“The Visible Hand”

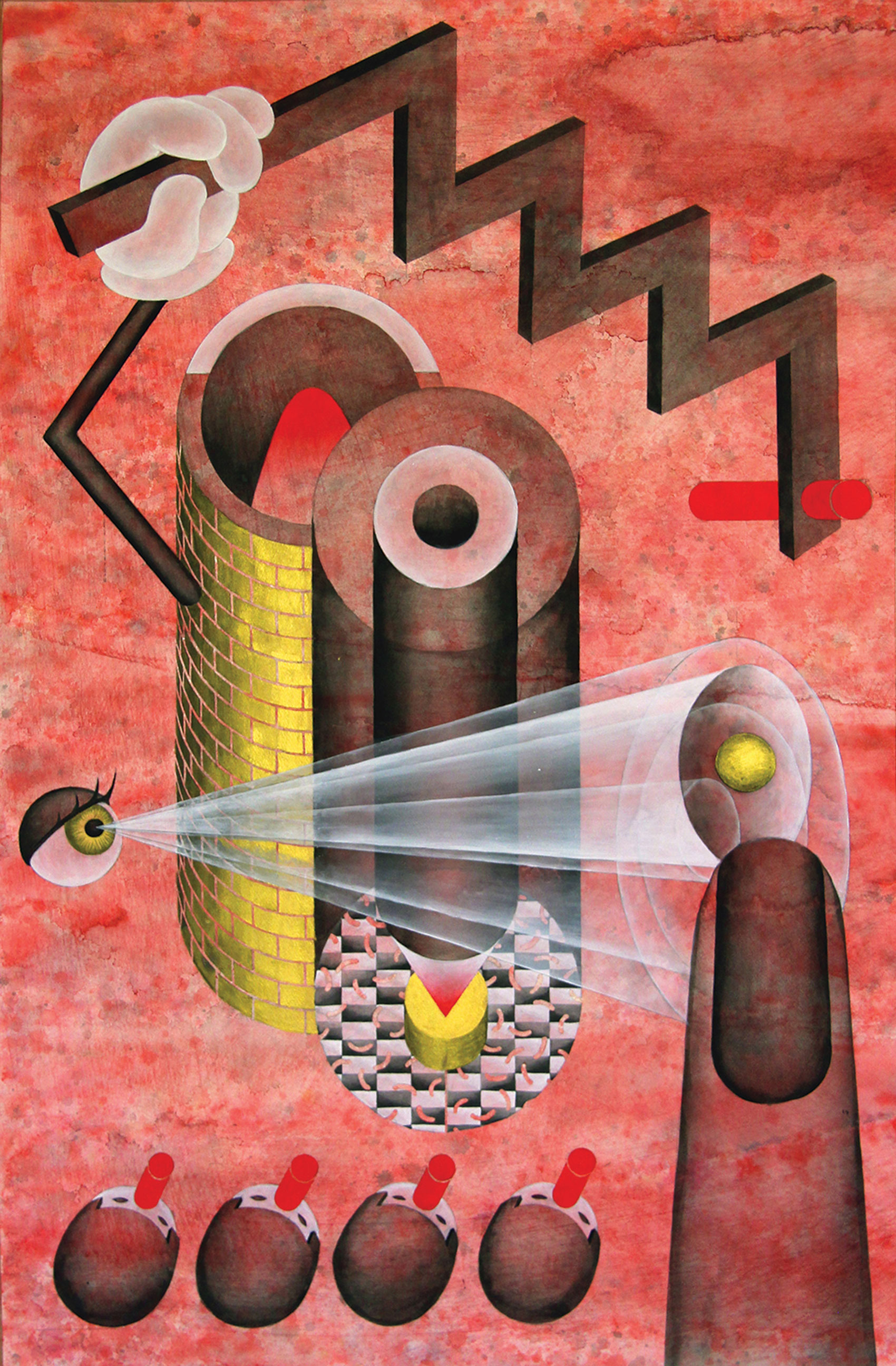

Jen Liu. The Pink Detachment: Principle of Secure Infrastructure, 2016. Acrylic ink, acrylic gouache, gold watercolor, and gesso on paper; 51.125 × 33.125 in. Courtesy of the artist and Upstream Gallery.

“Managers in dead offices devise control systems

that free the workers’ minds so they can focus on work.

Managers in living offices encourage individuals

to pursue self-actualizing goals.”

—Mónica de la Torre1

Let’s begin by dismissing the notion that a purely agonistic relationship between the artist and the institution still holds. Such a strict opposition, if it ever applied, has eroded, revealing the increasing degree to which the notion of an outside—an alternative sphere of production and circulation, safe from the reaches of institutional and corporate strongholds—also must fall. Artists today operate as administrators and consultants, grant writers and promoters, developers, coders, and graphic designers; they ride the wave launched in the sixties and accelerated in the nineties of the diversification of the labor force within the arts, a diversification that ceaselessly draws art practices closer to non-art professions.

This diversification initially enabled greater autonomy: the sixties and seventies saw the rise of artist-run spaces and institutions, as well as growing art and labor movements, like the Art Workers’ Coalition (AWC), born during periods of political turmoil and social upheaval. By the mid-nineties, figures like Andrea Fraser and Helmut Draxler helped to reframe the conversation about artistic labor within institutions in terms of services for artistic projects. These proposals would not only reframe the relationships between artists and institutions but also better define the nature of artistic labor, proposing a model for dealing with practical and material realities and ultimately, as Fraser writes, offering “a professional model of collective self-regulation.”2

Maureen Connor. Personnel 3, Portable Storage, 2002. Nylon, vinyl, steel, storage items. Dimensions variable.

The Visible Hand, curated by David Borgonjon at the CUE Art Foundation, New York, operates within this lineage, featuring five artists who fashion themselves as workers performing a range of functions, within and alongside institutions. They specifically address the turn toward the managerial. Yet, rather than attempt to form purely independent counter-economic or supposedly autonomous practices, they offer models of direct engagement, adopt executive strategies, and intervene within the quickly shifting set of relations between the artist and forms of management. In so doing, they open up opportunities for positions in consultancy, advocacy, and management that artists might occupy as skilled laborers.

In the late seventies, Michel Foucault had already developed a theory of the entrepreneur of the self, in which the neo-liberal subject becomes her own producer and thus becomes human capital. The entrepreneur of the self is mobile, flexible, innovative, and constantly growing. Here, the economic model of supply and demand extends to social relations and maps onto the individual’s relationship to herself as well. Today, the enterprising self is also becoming the managerial self, as innovation meets complex logistics and the demand for ever-more transparency and efficient workflow.

For Alfred Chandler, who coined the term “visible hand,” the so-called “invisible hand” of market forces described by Adam Smith in his eighteenth-century book, The Wealth of Nations, was replaced by the modern managerial enterprise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Thus the invisible hand—an imperceptible force balancing supply and demand of goods in a free market and resulting in incidental social benefits experienced by individuals—was supplanted by the visible hand of management at all levels of the supply chain, turning quality into a matter of logistics, bureaucracy, and administration. This too led to increasing hierarchies within management, a rise of professionalism within the corporate structure, and greater specialization of tasks.

Devin Kenny. Prix Fixe, 2012. Digital audio files, plastic, inkjet prints, network. Special thanks to Kevin Chen.

At the same time, small and big businesses alike have, since the fifties, assimilated and adopted a model of creativity and innovation at the core of their values and strategies; we have only to think of the upsurge in research and development (R&D) departments and the proliferation of think tanks.3 If the late nineties saw the rise of a discursive paradigm of self-organization—with its emphasis on emancipatory social relations, productive contestation, and unfixed or deregulated collective identity in the eyes of representative art-world institutions4—the emergence of start-up culture dealt these presumed independent artistic formations yet another blow. Social relations and reflexive practices, along with the vocabulary and methods of collective work and co-creation, could easily be repurposed for businesses churning out an increasingly innovating, multiskilled, and flexible workforce, to expand the reach of the so-called creative industries.

It is within this context—quickly and by no means comprehensively sketched here—that the artists in The Visible Hand are situated. As Borgonjon specifies, the five artists in the show “reflect in their work on the entire process of artistic production.” The exhibition thus traces an arc that reveals the many possible roles of the artist today while understanding artistic practice as intricately complicating the artist’s relationship to administration and management, corporate structures, the art market, education, and more intimate, affective relations.

In her conceptual practice, Chloë Bass weaves through situations like a choreographer or director, turning everyday occurrences, interactions, and encounters into subtle experiments in socialization. Testing different types of communication in predetermined and improvised contexts, Bass continuously reworks the contours and dynamics of collaboration, co-creation, and intimacy. In her multiphase work, The Book of the Everyday Instruction, she stages a number of interpersonal situations, including movement exercises, workshops, and studio-based procedures. Chapter Six of the project takes the kitchen as an experimental laboratory: recipes are drawn up to generate emotional states while the structures of production and consumption that govern the kitchen become terrain for conceptual exercises focused on conviviality and play. In this way, Bass assesses proximity and intimacy by casting their everyday vocabularies within the museum.

Chloë Bass. Gather the house around the table (House of Ceramic, Glass & Metal), 2016. Installation detail.

Maureen Connor’s ongoing project Personnel, begun in 2000, looks specifically at the artist’s embedded role within the art institution. In her interventions, she provides responses to staff members’ avowed or perceived needs and desires; creates solutions for storage, space occupancy, and exhibition design; offers methods for conflict resolution; and improves staff morale, amenities, and engagement with local communities. She takes on the role of a multifaceted human-resources mediator or consultant in devising direct strategies that are presented and enacted in the museum over the course of an exhibition. While staff members are called upon to carry out the scripts and procedures she develops, they also perform new roles within the workplace or perform their prescribed roles according to a new repertoire of gestures and attitudes. Here, the notion of a choreography or orchestration operates at an institutional scale to propose concrete, playful, and potentially transformational measures within the workplace.

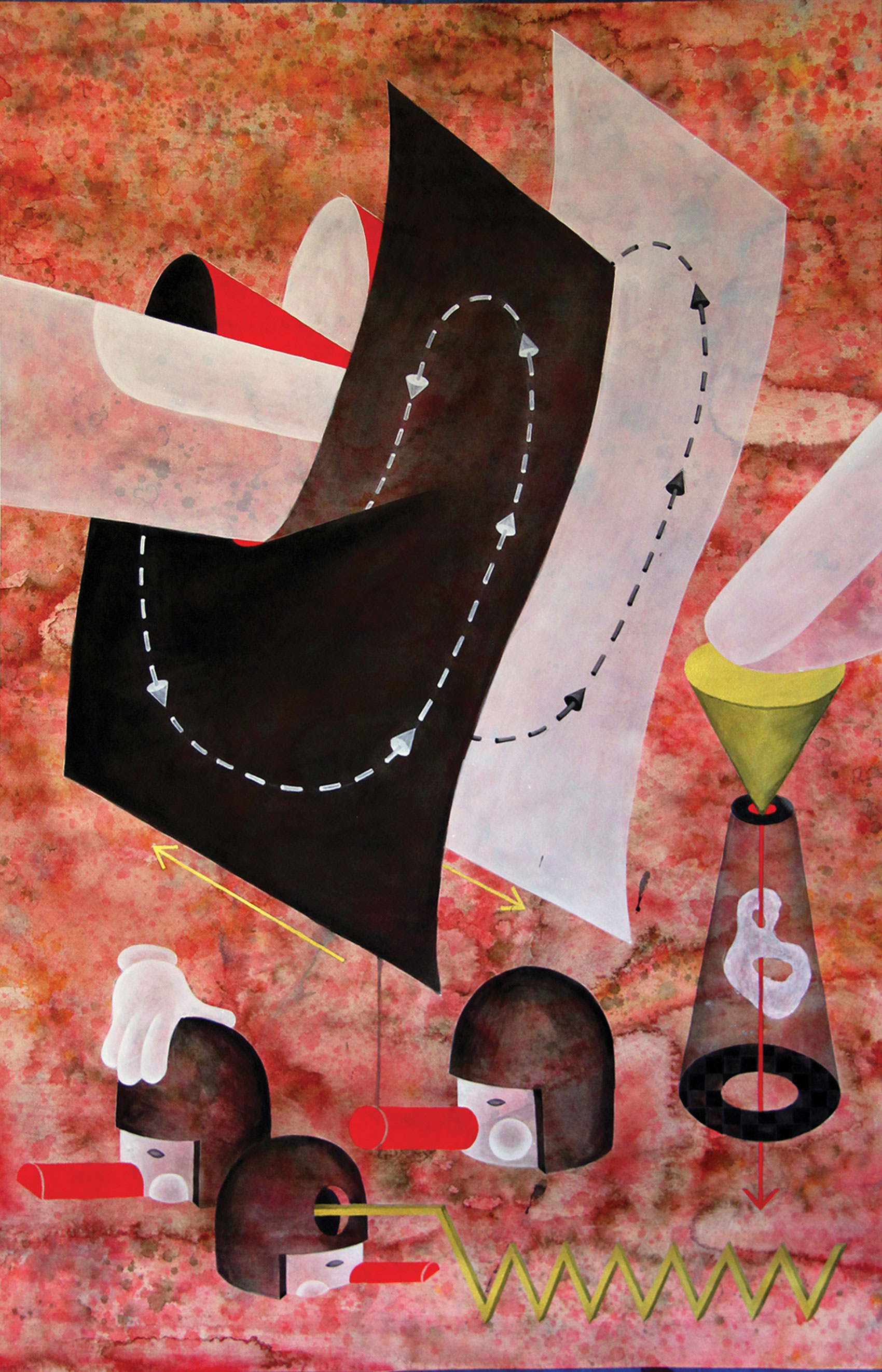

Jen Liu addresses questions of labor and gender within broader socio-economic and political contexts. If, like Connor, she works within a register of projection or speculation, hers takes the form of fictional narratives that privilege what she calls the “thin materiality of propaganda images, power sloganeering, and sci-fi speculation.” In her series of watercolor paintings, The Pink Detachment (2016), Liu considers the aesthetics of factory lines operated by a female workforce in southern China—a gendered choreography of labor that adopts both the coldness of serial, mechanized gestures and the liveliness of modeled, embodied forms. For Liu, visualizing female manufacturing leads to the image of a utopia of production, unmediated by outsourced labor.

Jen Liu. The Pink Detachment: Principle of Perpetual Catastrophe, 2016. Acrylic ink, acrylic gouache, gold watercolor, and gesso on paper; 51.125 × 33.125 in. Courtesy of the artist and Upstream Gallery.

Devin Kenny’s work echoes Liu’s suggested appropriation of the means of production and distribution. He circumvents the art market by internalizing its language and demands. His Subscription-based Art (2016) is a prototypical interface that gives patrons agency in determining certain criteria that will affect the works they commission. While market trends are under increasing scrutiny, with every peak and lull tracked, Kenny banks on a confirmed audience and does away with the unreliability of market demand. In this way, he both operates under the assurance of compensation for artistic labor and renders more intimate the scale of his collector base, taking the reins on monitoring, interacting with, and producing works for known quantities.

Also speaking to these specific economic pressures is the collective BFAMFAPhD (a name made of the acronyms for art-school degrees at the undergraduate, graduate, and doctoral levels). Ten Leaps: A Lexicon for Art Education (2015–ongoing) is a multi-platform work composed of a set of cards, an informative website, a number of workshops, and freely circulating syllabi. Through this project, the collective provides exemplars for conceiving of diverse economies in the arts. With a focus on generating economies of solidarity and networks of support, mutual aid, social justice, and democracy, Ten Leaps: A Lexicon for Art Education effects a rigorous mapping of all the stages of artistic labor and practice along the supply chain, covering everything from sourcing materials to transferring goods to representing one’s project. As a group that advocates for cultural equity and reform in arts education, BFAMFAPhD is prescient in its work, which attempts to answer urgent questions such as, “What is a work of art in the age of $120,000 art degrees?” What alternative economies of production can be put in place to support artists and producers as they work their way through the existing economy and the burdens precarious living and heavy loans?

Emilio Martinez Poppe and Susan Jahoda. Ten Leaps: The Card Game, 2016. Part of Ten Leaps: A Lexicon for Art Education, 2015-ongoing. Cards, website, book, syllabi. BFAMFAPhD Contributors Susan Jahoda, Emilio Martinez Poppe, Caroline Woolard.

Accompanied by a series of public programs, including workshops on artists’ administration of institutions and a symposium on art as service focused on the model of the artist as consultant, The Visible Hand expands the notion of the managerial to a range of practices that are not merely art analogues but also have implications for broader discussions of labor, political economy, and institutions today. As art economies and forms of artistic labor face increased insecurity and duress under the new Trump administration, The Visible Hand boldly proposes that a reconsideration of the role of the artist in social and economic relations could be beneficial to the generalized reconfiguration of social, economic, and political life that is required today.

1. Mónica de la Torre, The Happy End/All Welcome (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2017).

2. Andrea Fraser, “How to Provide an Artistic Service” (lecture, The Depot, Vienna, October 1994).

3. For more on the postwar context, see Lucy Hunter’s recent talk at The James Gallery, CUNY Graduate Center, “Creative Destruction: Bell Labs in the 1960s” (September 2016), part of her ongoing dissertation research, Last accessed November 17, 2016.

4. See Stephan Dillemuth, Anthony Davies, and Jackob Jakobsen’s “There is no alternative: THE FUTURE IS SELF-ORGANISED,” accessed November 17, 2016.

Editor’s note: This essay was written by the Art21/CUE Writer-in-Residence in conjunction with the exhibition The Visible Hand, on view at CUE Art Foundation, January 7–February 15, 2017. This text is included in the free exhibition catalogue available at CUE and online.

The Art21/CUE Writing Fellowship provides each writer with a mentor, an established art critic appointed by the International Association of Art Critics USA Mentoring Committee. Rachel Valinsky worked with the art historian, curator, and editor, Charmaine Picard.