Deep Focus

The Role of Online Archives in Contemporary Art and Activism

A member of the press interviews a protester near the Ferguson Police Department, August 11, 2014. Dale D. Gebhardt, “Interview,” Documenting Ferguson, accessed January 12, 2017.

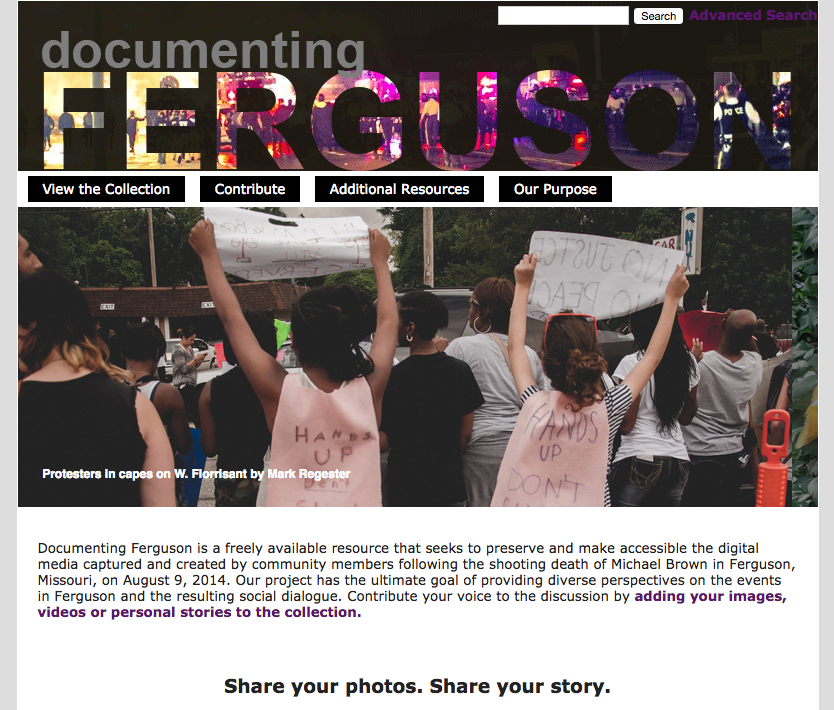

Recent years have seen an increased presence of the archive within contemporary art. Scholars and curators have pointed out the myriad ways that the form, function, and concept of the archive are appropriated by artists, underscoring their historical weight and capacity to engage us. Along with practitioners in the art world, journalists and activists are increasingly looking to the archive as a form of display, particularly as mediated through the Internet. At the outbreak of Syria’s civil war in 2011, for example, the New York Times created “Watching Syria’s War,” an online project that presents in-depth news coverage accompanied by amateur videos sourced from YouTube. In September 2014, Washington University in St. Louis created a website to document the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, inviting individuals to upload photos, videos, newspaper clippings, and other content related to the protests. Using the tagline, “Don’t let these images be lost to history,” Documenting Ferguson became a crowd-sourced archive that is at once educational and evidential.

The strategic practices of creating and maintaining an archive—the collecting, organizing, storing, and presenting of documents—are appealing to artists as methods to make sense of today’s constant bombardment of information and images. Whereas trained archivists typically led the production of archives, increasing numbers of artists are assuming this responsibility, particularly within the context of social-documentary photography.

Documenting Ferguson (Homepage, Documenting Ferguson, Accessed January 16, 2017).

A critical example is Susan Meiselas’s documentary work in Kurdistan. The project began in the late 1980s, when Meiselas accompanied a forensic anthropologist to document the mass graves in the region. Feeling that she needed more historical context to understand what was happening there, Meiselas turned to archives for guidance in her research and traveled to private homes to find photos in personal collections. In her resulting 1991 book, Meiselas embeds her own and historical photographs within a timeline of Kurdish history, creating a selected photographic archive of the region.

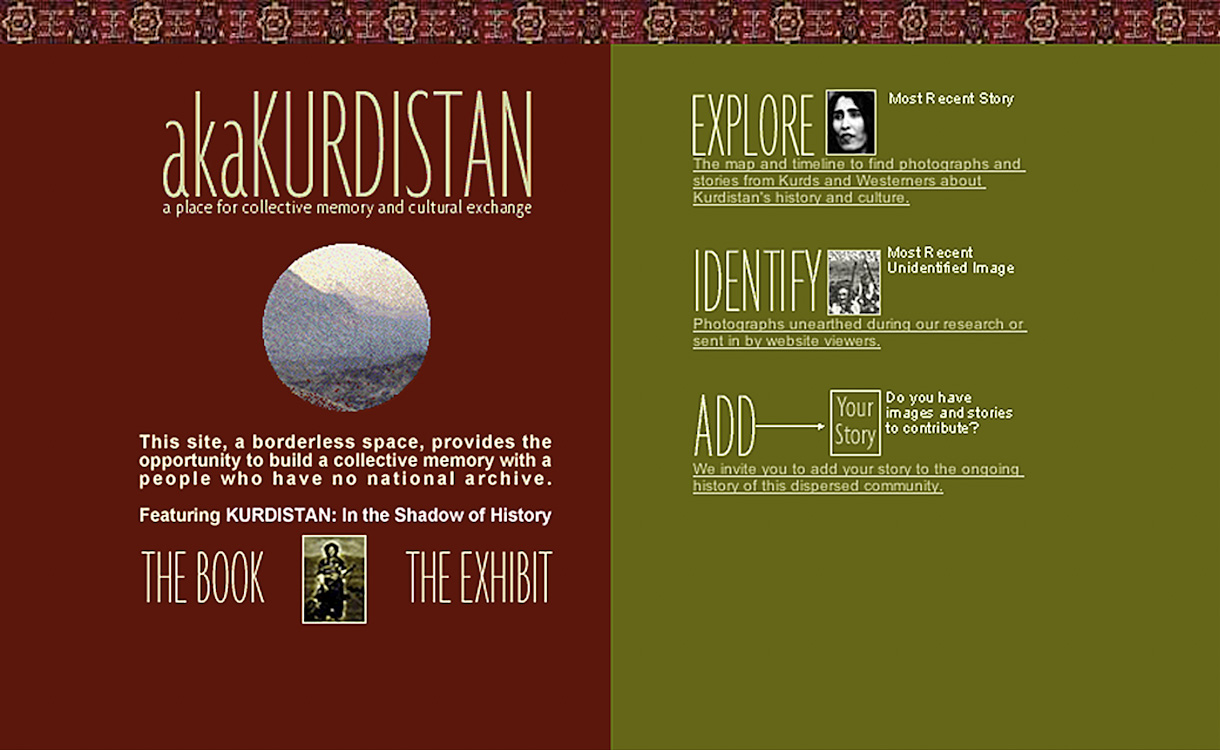

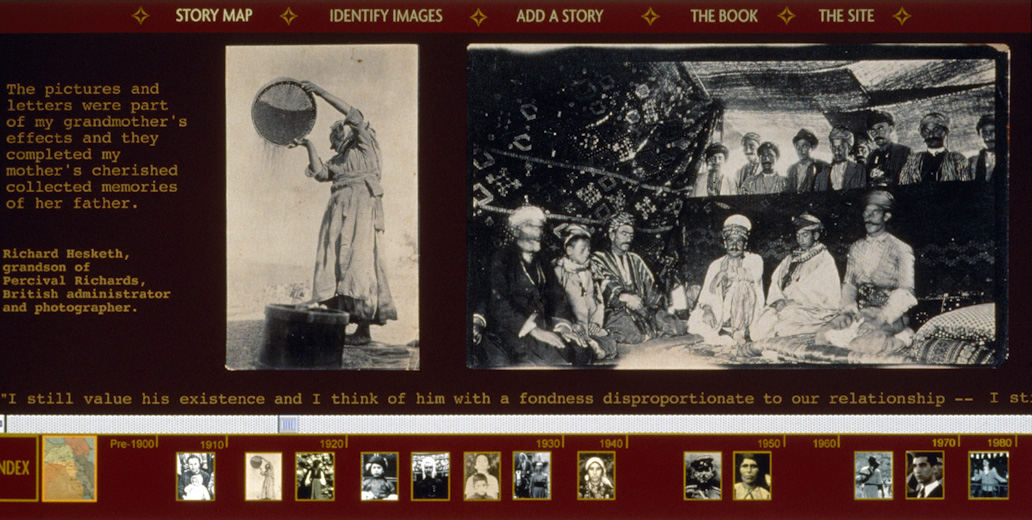

With the advent of the Internet, Meiselas saw a new strategy for engagement. In 1997, she launched the website aka Kurdistan, where viewers could explore the history of the region through photographs and text, add context to rare or personal images related to Kurdish history, and contribute their photographs and stories. Thus, Meiselas’ book became a digital, crowd-sourced archive of photographs, texts, videos, and documents dedicated to Kurdish history. The decision to create the archive was rooted in its flexible and inclusive form, as well as its ability to engage a greater audience. The archive enabled a space for historical reconstruction that was rooted in evidentiary truths and aspirations for political recognition. What began as a document in time was transformed into a platform in which to trace time—past, present, and future.

aka Kurdistan. (Accessed January 16, 2017.)

As projects like aka Kurdistan or Documenting Ferguson show, the role of the citizen, particularly as a producer of content, is increasingly critical. The online archive is a way of weeding the thousands of images taken on camera phones every day; it offers greater accessibility of and context for the images and videos and lets the public engage with information embedded within photographic narratives. Indeed, as images both current and historical continue to proliferate, the role of many photographers and artists has shifted from documenter to collector.

Furthermore, recent projects—like Akram Zaatari’s extraordinary Arab Image Foundation, or even Rhizome’s institutional initiative to preserve digital art—emphasize the importance of collection. Reimagining and re-presenting content rather than exclusively creating it, Meiselas, Zaatari, and others show and contextualize what we need to see.

Screenshots of the akaKurdistan website. Susan Meiselas, akaKurdistan, 1997-Present. Source.

The online archive is not without downsides. Encompassing large quantities of content, the interface must balance user-friendliness with aesthetic considerations. Creating a visual vocabulary that communicates to a wide audience is imperative not only for the archival project’s functionality and appeal but also for its accessibility.

Many archival projects come out of communities that are attempting to define their history or are looking to create spaces in which that history may be communicated. While online archives have flaws, they more importantly have capabilities. And when an archive is constructed through the eyes of an artist, it has the potential to reveal, engage, and educate differently.