Teaching with Contemporary Art

The Process is the Product

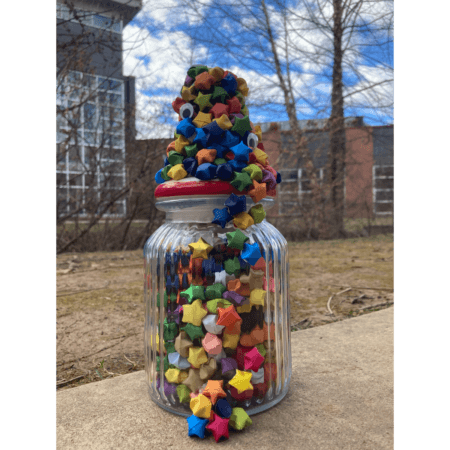

Photo by Andrea Mancuso.

The camera in its simplest and most complex form operates like an eye. Light enters the pupil or the lens aperture and is projected upside down and backwards onto the retina, or the picture plane. The brain makes sense of these images by filling in gaps, focusing on selective areas, adjusting the color, and presenting the world right side up and forwards.

In the first days of classes, students make a pinhole camera. They start by repurposing a discarded box—usually a shoe box, maybe one that was once home to their new school shoes. They build a camera out of that box, gaffer’s tape, black spray paint, and aluminum, recycled from used soda cans. The boxes are completed when any light leaks are taped up, and the only opening left has been covered with a perfectly round pinhole aperture, made by poking a pin through the aluminum. The cameras are loaded with a sheet of photo paper and the aperture covered by a shutter made from black electrical tape. The box cameras are placed outside and when the electrical tape is removed light is projected through the pinhole opening. After an exposure of 1–3 minutes, the tape is returned. The box cameras are gathered and brought into the school darkroom where latent images hidden on the gelatin-silver photo paper wait to be revealed through a chemical process.

Photo by Andrea Mancuso.

As the photo paper is bathed in the developing solution, images emerge on the page, as though by magic. As a class, we consider the fact that the image was already there (latent) even before we could see it in the developing bath. The students refine their cameras and exposure times, they problem solve and slowly each one has some success; the process takes 1-2 class periods and lots of trial and error.

Photo by Andrea Mancuso.

Together the class learns how the camera helps us see. Building a camera from scratch connects the camera to the physiology of our eyes and emphasizes the way in which vision–artistic vision–can drive an understanding of photography and the way we see and picture the world. Making photographs from a camera built literally from garbage presents an opportunity to repurpose material and build new pathways to train our brain to see more. Students learn to believe in the pinhole camera only after they capture an image, because the physics of light illustrated by the pinhole camera seems too simple to be true. The latent image is alive on the photo paper even when we can’t see it. The students learn to believe in complex visual understanding and to develop patience and craftsmanship in managing light leaks that mark their images. Light doesn’t discriminate between a fancy camera or a carefully taped box. The process is the same.

Our work with pinhole cameras makes the class curious. It only seems right to push this curiosity, transferring what they have learned from the hand held object, the camera, into the space we occupy, the room. The photographer’s studio space is the world; building a camera obscura transforms a room into a camera. Art makes the obvious extraordinary.

Photo by Andrea Mancuso.

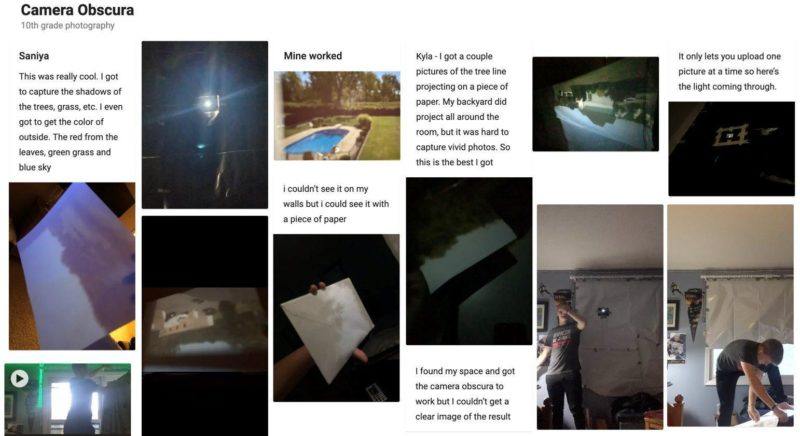

The pinhole camera exercise challenges students to rethink the boundaries of their artistic spaces. If the classroom can become a camera, can they bring that knowledge home? Can they begin to see art everywhere? For inspiration, we can look at the artist Do Ho Suh, and the way he transformed his apartment into a large drawing; Andrea Zittel, and how she transforms the idea of a home into an artwork in some of the most inhospitable locations; Zoe Leonard’s conversion of a giant gallery at the Whitney Museum into a camera obscura. ; or Abelardo Morell, who made camera obscuras in his hotel room and traveling tent. The home and the room become places of transformation, marvel, and ingenuity. In a group discussion, we can explore the process further by reverse engineering the images in a slide show, asking each other “What do you see? What do you know? How do you know it?”

Photo by Andrea Mancuso.

The process is deceptively simple. Pick a room at home with a window, block out all the light, and place a small aperture (a hole-punched hole in a small piece of aluminum) in the window so that the light from outside can pass through. Wait and watch as the world outside is projected through the hole into the room onto the opposite wall and ceiling, floor and furniture. The process is the product. Students drive their own discovery as their eyes adjust to the darkness and they slowly see the images from outside appear in the room.

Challenging students to document their camera obscura constructions brings them into confrontation with the limits of different media. Students may try to photograph the image on the wall and fail—the room is too dark for the image to register on their camera phones. Some students discover that they can hold a piece of paper close to the aperture to get a brighter image. Some photograph the black plastic. Others make a time-lapse video of the work they did building the camera. The irony of this project is that the image from the camera obscura is rarely recorded in a way that matches their experience of being in the transformed room. Students return to class with stories of their process and describe the image, often without photographic proof. This is OK; in fact, it reminds us of what we learned in the darkroom. The latent image is there even if we don’t see it. Students hold images in their minds even if they are not adequately recorded. The camera obscuras filled the room with an image even if the student does not have the image to prove it. Experimenting with this technology teaches us about photography as an art form that is an extension of our physiology. Photography enables us to see the way we perceive and the image exists even where it is not revealed.