Deep Focus

The Issue Of Perspective

Recently, as I scrolled through my Twitter feed, I saw screen grabs of homophobic tweets that had been made under the handle @Boity, who is a well-known South African actress, TV host, entrepreneur, and rap artist with 2.4 million followers. I concluded that these were mistakes, probably “fake news.” It wasn’t until I saw an apology tweet from Boity that I realized she had indeed sent those tweets nine years ago, criticizing gay and lesbian storylines in popular soap operas.

In her short and direct apology, Boity states that she was a teenager at the time and that her opinion on the topic has since changed: “A decade ago, I was naive, homophobic, young, and didn’t know better; I was 19 and my views on sexuality were warped. We grow, our views change, and we do better. It’s gut wrenching and embarrassing to see them now; however, I am not the same person I was 10 years ago.” Members of the public have been adding their voices; some followers have welcomed her response while others believe there are double standards in the public backlash, stating she would have received harsher criticism had she been caught with racist tweets.

In South African news media, there is little room for me to freely report from my Black lesbian perspective

As a person who identifies as a Black lesbian, digesting the original tweets and the recent retraction from a fellow Black woman leaves me in an awkward position. During the period of Boity’s offensive tweets, hate crimes in South Africa perpetuated against Black lesbians were making national news headlines. While many cases of hate crimes against the LGBT community don’t make it to the mainstream media (as is the case with the fatal stabbing of Motlhatlhedi “Gustav” Modise, a trans woman from North West province, whose body was discovered on September 2, 2018), the 2006 murder case of Zoliswa Nkonyana (age 19), the 2007 double murder of Salome Masooa (age 23) and Sizakele Sigasa (age 34), as well as the killing of the former national women’s soccer team player, Eudy Simelane (age 31), which received both national and international coverage, had garnered enough attention for a media figure like Boity to know about the risks facing Black lesbians, if not the LGBTI community as a whole. It raises the question of our personal responsibility when we contribute to debates and dialogues that involve these sensitive topics. One of the country’s Sunday papers dated September 2, 2018, had the front-page headline, “My Hubby Loves Men. Fed-up Woman Spills Beans.” Looking at the full-page article, one realizes that the focus of the story is on other issues; the headline is used to sensationally catch the reader’s eye, but at what cost?

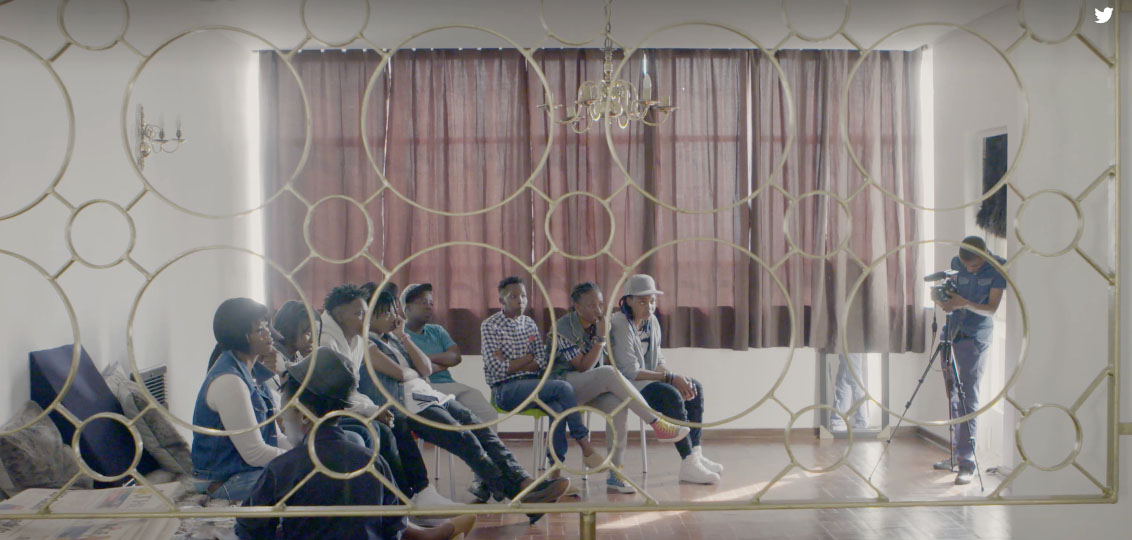

Lerato Dumse with camera on far right, from the “Johannesburg” Episode in Season 9 of Art in the 21st Century.

Consuming South African news media requires turning a blind eye to a lot of subjective opinions when it comes to reporting on race, politics, and sexuality. It is no secret that media ownership in South Africa has not diversified enough, especially concerning Black female ownership and specifically Black lesbian–owned and –operated media. For lack of a better description, it is interesting to read articles and listen to media reports connected to the highly publicized “state capture inquiry” that is looking at corruption and alleged looting of public funds in South Africa. There is no longer mention of the corruption allegations against Mcebisi Jonas, the former deputy finance minister and a media darling. These days, we are constantly reminded of his noble act of turning down a 600 million rand bribe, which was offered to him by a man whose name he failed to know. (I was gobsmacked that a military-trained cadre would not succeed with introductions!)

White South Africans are still influenced by the propaganda spread by the racist apartheid government

For those of us young writers who have enjoyed media- and creative freedom, coming to the realization that the real world doesn’t have time for our perspectives can be a frustrating reality check. In pitching stories, I find myself trying to sound correct to the advertisers; they keep the company financially afloat, after all. This is the state of affairs that many young journalism graduates enter.

In South African news media, there is little room for me to freely report from my Black lesbian perspective. When I worked for a newspaper on the community that I had spent my whole life in, I was expected to pitch stories to be understood by a White editor who had never been there. What the editor understood was how she imagined things to be, which is not how things actually are. Unlike in the United States, where gentrification has become cool, White South Africans are still influenced by the propaganda spread by the racist apartheid government, ensuring that people live separate lives and that White people don’t venture into townships.

One of the ways to survive in journalism is by being overly critical of the ruling party. I have found that the level of anger that is expected from a journalist reporting on the ruling party far surpasses the level of anger such a journalist is allowed to have against the injustices and murders that Black South Africans were subjected to under apartheid.

Writing for organizations that support diversity of gender and sexuality allows us to express ourselves in times of joy and sorrow.

This brings us to question the issue of agency. I often wonder who controls our anger, as South African citizens and as people tasked with the responsibility of reporting about the current, historical, and future affairs of our country. It seems as if the mainstream media outlets hold the button or remote of forgiveness, leisurely flipping through the channels and pages and deciding who and what will be forgiven. These outlets make no attempt to hide their biases and continue to erase what does not attract advertisers. But by now, the question should be: Who are these advertisers?

As a thirty-year-old Black lesbian from the township, the probability of me making the headlines as a hate-crime victim is high. My existence in any other context does not sell newspapers and is therefore of no interest to the advertisers, meaning my story will not live beyond that diary meeting. Writing for organizations that support diversity of gender and sexuality allows us to express ourselves in times of joy and sorrow.