Deep Focus

The Digital Museum: A Conversation between Loic Tallon and Julia Kaganskiy (Part II)

The New Museum. Photo: Marc Teer.

For the second half of “The Digital Museum,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s chief digital officer Loic Tallon and NEW INC director Julia Kaganskiy continue their discussion on the recent developments in the digital role of museums and the future of their digital presence and influence.

As leaders in the digital museum space, both Tallon and Kaganskiy have been at the forefront of some of the field’s most exciting projects: In 2014, the New Museum founded NEW INC, the first museum-led cultural incubator, led by Kaganskiy. And in February of this year, Tallon’s team at the Met launched an Open Access policy, which made all images of public-domain works in the museum’s collection accessible under Creative Commons Zero (CC0) licensing. (Read Part I of the interview here.)

Loic Tallon—How [do the goals of the Met digital team] resonate with people working in the New Museum?

Julia Kaganskiy—Because the New Museum doesn’t have a permanent collection, we tend to be more open-ended with goals for the museum; things could be as simple as new forms in exhibition design. There’s one person at the NEW INC who’s working on a tool to streamline the exhibition-design process and make checklists that can be updated in real time.

That’s a really valuable position to take. What’s your advice to people who are doing projects that relate to museums, to make them successful?

Have a Plan B! [laughs] Cultural institutions are often challenging to work with: they don’t have huge budgets; they are resistant to change. How does one bring change to organizations that are conditioned to be skeptical of trends and fads? They’re built to resist and cut through the bullshit, and so they take their time deciding whether they are going to pursue something or whether they’re going to engage and how. They’re thoughtful, studious, and meticulous, and the idea of prototyping is anathema to how they work. To put something out that is not a finished product—that has not been through a rigorous quality-control process—is unthinkable to them.

It subverts decades of how museums work. If you were to ask a curator about how to create an exhibition, she would probably talk about the research on which the exhibition is based and the work steps needed to design a perfect exhibition for the opening day. Creating a website is different; we acknowledge that it’s not going to look perfect on launch day, but we launch it anyway and then listen to how our users are using the website in order to inform how to develop it in a way that is meaningful to them. It’s a very different way for museums to work. It is not even a technology challenge; it’s a human challenge.

But what you just said assumes that the curator is able to reach perfection with her exhibition, and I don’t know that is necessarily true. I don’t know if we can reach perfection with a website. What we have is data about how people are interacting with it, which will quickly demonstrate to us where there are problems and gaps. And we can collect similar data about how people are navigating an exhibition and make adjustments to it in real time, based on what’s working and not.

I agree, but that is a change of practice. Imagine: an exhibition in which the museum surveys visitors every day and makes one incremental change each night to hone the exhibition design. The exhibition would be “more perfect” on closing day than opening day. Of course, that’s not the current exhibition practice, but maybe in ten years, it will be; we’re learning from the digital space, where more people are getting into user analytics, and it doesn’t seem too farfetched to imagine that thinking being applied to a physical space. I agree with your point about perfection: how we get there is important, and can we get there?

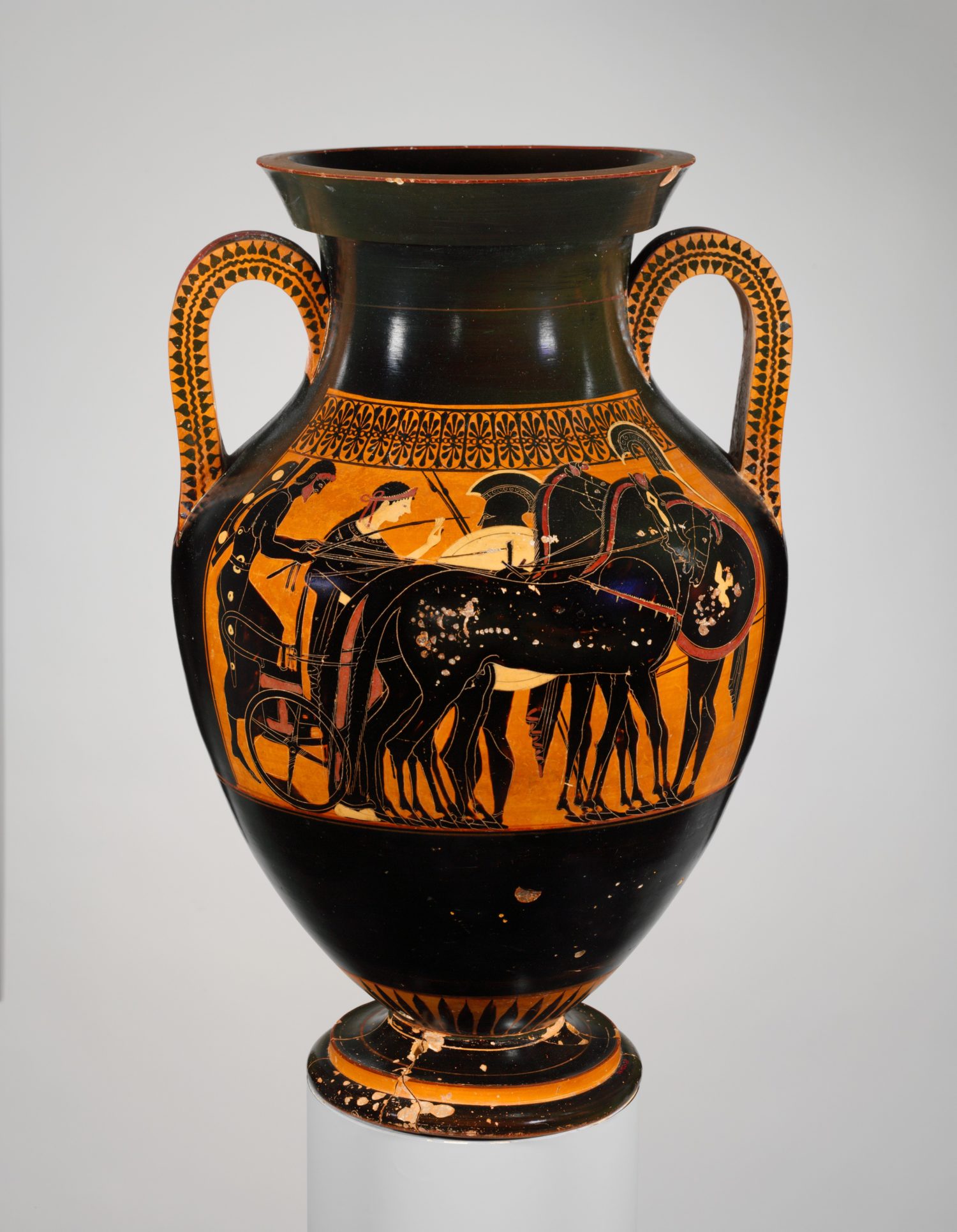

Greek/Attic Terracotta amphora (jar), c. 510 B.C. Terracotta; 20 1/8 inches. An image in the public domain, accessible via the Met’s Open Access initiative.

I guess it depends on whether curators see themselves as authors or public servants. Many curators nowadays take on an authorship position, where they don’t care about the data or audience feedback because their work is not about pandering to the public.

I’m not sure I agree. I think curators are taking artworks and telling stories with those artworks based on research. I think that’s an important practice. They are looking for truths in these artworks to help us better understand our identities. We live now in an age when the view of an expert seems to be quickly replaced by the view of a crowd. But I feel comfortable promoting the view of the expert. And many curators already are engaging with visitor feedback on a daily basis, on social media. When Keith Christiansen, one of the top scholars in the world on European paintings, posts on Instagram, he’s entering into discussions with people who might ask questions about the object. It’s a simple interaction that didn’t exist before social media. Even three years ago, having access to him would be a challenge.

Very recently, our head of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts, Luke Syson, had an Instagram conversation [with Christiansen], inspired by a particular artwork. It was spontaneous and accessible, and people responded to the conversation. I think there is a place for the expert voice. I would love to get users to feel more proactive in conversations. I believe most of the curatorial team would like to do the same; it’s just about finding the right structure for it. Social media has provided us with a strong start in that area. There’s still room to improve, but people are experimenting and finding their comfort level.

I was referring to an unwillingness to open the floodgates, and maybe that will go away. But in this age, when expertise is under attack, it is important to celebrate scholarship and to create a dialogue between that deep knowledge and a more popular knowledge. When the two are in dialogue, meanings can arise that are probably more effective and engaging than any single interpretation.

And more relevant. Going back to the 3.7 billion internet-connected people: they’re only going to care about a collection if it’s relevant to them—if it tells a story that intrigues them, or reminds them of something special in their past for example. Our work is aimed at creating those moments of relevance and helping to connect an incredible body of scholarship to an audience that probably wouldn’t ever want that bulk of content; they’re looking for one or two facts that inspire them and make the object relevant to them. There’s a huge potential, but it’s a challenge to make the right facts available to the right people at the right time. There are so many barriers and different ways of making meaning around the world that we have to respond to.

A space like [NEW INC] has a group of people who don’t see the barriers, who can create from the outside without restrictions and without boundaries. At the Met we need to work in a way that brings the museum with us. We want to make the Met comfortable in the digital space, to the degree that eventually everyone will be working with digital, when there is no longer a digital department. If I was the last chief digital officer at the Met—that, to me, would be success.

Nigerian (Court of Benin) Warrior and Attendants Plaque, 16th–17th century. Brass; 18 3/4 inches. An image in the public domain, accessible via the Met’s Open Access initiative.

I wonder what new forms of knowledge-making, for lack of a better term, will look like. You’re talking about taking data and combining it in different ways or linking it to contextual records, as in the case of Wikimedia. I’m curious about how we create the next YouTube or Netflix—some hub where knowledge exchange, learning, and engagement with these objects occurs in a new way. Like fan fiction—what does fanfic for museums look like?

Fan fiction for museums is an awesome idea. How do you build something for and with a community? It’s got to be relevant to people—who would build it? How do we encourage fanfic for museums?

Should it come out of a museum?

Perhaps in the future, if we decide that’s where the greatest value is. What would be the best way of creating a fanfic way of interacting with the collection? An incubator space would feel more suitable than a museum.

Companies like Microsoft and Google are no longer hot technology startups; they are now the incumbent players, the entrenched, dominant forces. Yet they have departments that are tasked with researching technologies ten, fifteen, twenty years into the future, all for the purposes of getting there first, patenting it so no one else can get at it, and helping the organization anticipate what’s coming and hopefully prepare for it. Often they’re too early; like, they’ll invent social-media networking or Skype before people are ready. But they get to the idea. They get to the thinking, and it informs the organization’s idea of what is possible. And I think that is vital, in terms of opening the spectrum of possible realities. We have nothing like that in cultural institutions.

You do have NEW INC. But it’s different for the Met; we have an iconic physical presence, a building. The success metric most frequently promoted is the number of people who come to the building; the Art Newspaper cites attendance figures. To look at serving the museum’s mission as bringing people not just to the building and the websites but even further requires a change in thinking. What will be next? Do we invest in an in-house incubator; can nonprofits do that? I don’t see many models for it. MIT Beta is a great example of a space that is trying to define future forms. There are some interesting lab models of integration with museums: we’re looking at the Carnegie Museum of Art, in Pittsburgh, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

There is still a need to figure out how we work with the tech community in a way that’s integrated with the mission, in which the change takes root within the institution, as opposed to an external force that people find unsettling. My goal is the digital transformation of the museum: for the digital department to change the museum’s practices from within and digital to become part of everything in the museum.

Vasily Kandinsky. Kleine Welten II (Small Worlds II), 1922. Lithograph printed in black, red, blue, yellow; 10 × 8 5/16 inches. An image in the public domain, accessible via the Met’s Open Access initiative.

Although NEW INC is trying to create more integration with the New Museum, which is next door, we are actually not focused on disrupting it. We are working with eight companies that are specifically addressing museum technology, focused on audience engagement, but that’s new for us. Our focus has been guided by the New Museum’s mission statement: new art, new ideas. NEW INC is the new ideas portion. There’s some new art in here too, but I’m really interested in what disruption means—for society and culture at large, for the creative industries, for cultural institutions, and for arts education. What does it mean for artists who are working with new tools and ways of disseminating and presenting their work and connecting with audiences? And for artists making work that does not fit inside a gallery or into the art market?

Art that doesn’t fit inside a crate.

Exactly. What are the new ways of working, the new economic and business models, that are going to support that [kind of artwork], be they nonprofit, social enterprise, or for-profit? They’re often decentralized, networked, collaborative, and interdisciplinary. What are the new technologies that are going to change the way that we communicate, navigate space, and understand our reality? Those are some of the questions that drive NEW INC. Part of the reason that it’s structured so expansively is because I’m interested in building capacity and developing skills, knowledge, and resources in the creative industries more broadly. I’m also more interested in the ecosystem—of which museums are but one major and important player—that is deeply intertwined and interdependent.

I like that you aren’t putting boundaries around the practice.

And we socialize people across disciplines. We have architects, CGI artists, and fashion designers. The hypothesis is that—through the collision of different disciplines, skill sets, and ways of thinking and working—new ideas emerge. The shared space facilitates the combining and applying of frameworks from one environment to another. And this approach is not new.

You’re right: it’s not new. We’re doing the same thing in our Met community (but without CGI artists or information architects). But we need to encourage that collision and that dialogue between the curatorial teams, collections information team, content team and products team, who are trying to re-envision how to create a compelling engagement with an artwork, how to tell a story through a thirty-second video for example. Because that’s what people want to see on Instagram. And sometimes, [the process] may involve a collision but ultimately that’s probably a good thing: it forces us to think differently about a problem.

And we in the museum industry need to get out of our comfort zones. The boundaries within a space like NEW INC are very [elastic]. It is part of what makes it challenging, but it also feels like a productive friction. It drives me and my team crazy (and some of the community, I’m sure). But it produces amazing collaborations, and I would wager that it will have an impact on people’s work for years after they leave here, even if they may not immediately recognize it as valuable. That’s what I hope people take away.

I would say the same about the Met team and helping to connect people around the world to the arts by giving them access. It feels like we’re doing the same thing, but the level of disruption and conversation one can currently have inside a museum compared to that which one can have outside it is different by an order of magnitude.