Deep Focus

The 1913 Armory Show: America’s First Art War

William-Adolphe Bouguereau. The Wave, 1896. Oil on canvas; 47.64 × 63.19 inches (121 × 160.5 cm). Private collection.

America has been an epicenter of avant-garde art for a long time, but this was not always the case. The reasons for the rise of the American art world are plural and complex. In part, this rise resulted from a mix of post-World War II affluence, which created collectors, and Cold War politics, which weaponized American modernism and deployed it as proof of cultural superiority. But the United States art world’s claim to center stage also rested on America adopting and modifying European avant-garde styles. If, as Serge Guilbaut put it, New York “stole the idea of modern art,”1 it had to first know about modern art. Perhaps no single event marked as epochal a moment in America’s avant-garde awakening as the International Exhibition of Modern Art held at New York’s 69th Regiment Armory in 1913. Tellingly, the Armory Show (as it is popularly known) did not just jolt young American artists into a new dialogue with experimental forms; it also polarized the American public and started what would be a long and loud battle, between people who claimed to be championing the most excellent and advanced artistic ideas, and others who thought those people were obviously, painfully, full of it.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, artists were trained at academies, in which idealistic realism reigned supreme. Academic art tended to promote softened, perfected forms and to render the artist’s hand invisible. Many European artists of the mid-1800s rebelled against academic art, but in America at the turn of the century, academic styles and modes of exhibition were still strong. So, in 1911, four young artists who were fed up with the academy—Jerome Myers, Elmer MacRae, Walt Kuhn, and Henry Fitch Taylor—began meeting at the Madison Gallery in New York to discuss new strategies for exhibiting art in the United States.

That group eventually gave birth to the Association of American Painters and Sculptors (AAPS), composed of young anti-academy artists. In 1913, AAPS organized the Armory Show. By this time, the purview of AAPS had expanded to include bringing the newest European art to American audiences. The president of AAPS opened the show with these words:

The members of this association have shown you that American artists—young American artists, that is—do not dread, and have no need to dread, the ideas or culture of Europe. They believe that in the domain of art only the best should rule. This exhibition will be epoch making in the history of American art. Tonight will be the red-letter night in the history of not only of American but of all modern art.2

The members of the association felt that it was time the American people had an opportunity to see and judge for themselves concerning the work of the Europeans who are creating a new art.

So, what would Americans make of this new art, when given the opportunity to “judge for themselves”?

Paul Cezanne. An Old Woman with a Rosary, 1895–96. Oil on canvas; 31.7 × 25.8 inches (80.6 × 65.5 cm). Courtesy of the National Gallery, London.

On display at the Armory Show were more than twelve hundred works of art by more than three hundred artists from the United States and abroad. There were newly minted Old Masters: Cézanne, Van Gogh, and Gauguin were well represented. But the work that captured people’s imagination—and, in some cases, enraged them—was of a more recent vintage. Contemporary avant-garde movements got the most attention, and it was the disorienting intensity and spatial decomposition found in Cubism that was the talk of the town. One painting, in particular, became almost synonymous with the succès de scandale of the Armory Show: Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (1912), a painting by French artist Marcel Duchamp, who, in later years, would develop quite a reputation for attracting adversarial attention to himself.

Marcel Duchamp. Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. Oil on canvas; 57 7/8 × 35 1/8 inches (147 × 89.2 cm). © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris / Estate of Marcel Duchamp.

Why did Nude stand out from the show and from other Cubist work there? First, its pictorial fragmentation was more violent and jagged than other similar paintings; its lines were closely knitted and overlapping, resembling sketch-work as much as traditional brushstrokes. While other Cubist works of the period stressed the multiplicity of a single moment—which is to say, an artist might render a subject from multiple angles—Nude combined this strategy with a Futurist-inflected temporality, simultaneously representing multiple moments in time. So, it played with at least two different kinds of psychic torsion. In other words, the painting appears to portray a woman at many, various stages of walking down a set of stairs and does so from many, various angles. This way of dealing with time aligns the painting with Eadweard Muybridge‘s (and others’) early photographic motion studies and, by extension, with cinema. But Duchamp combined this almost diagrammatic linearity with strategies of visual obstruction, placing the work uncomfortably between legibility and illegibility: now you see it, now you don’t. In a way, Nude angered people because they understood it too well, but also not enough: what is really frustrating to a viewer is a false start, not a foregone conclusion. The bottom half of the painting contains at least six triangular shapes that can easily be seen as bent legs; the middle section has five ovals that call to mind hip bones. But while you might be able to make out a face in the upper right-hand corner, the angular chaos in the upper left section of the painting cannot be easily synthesized. By rhyming this mindful disorientation with photography and cinema, Duchamp seemed to be saying something about modern life: maybe perception and cognition were changing at the rate of technology. Or the speed of light.

The most famous condemnation of Nude drew on a peculiarly modern metaphor to make its point. Julian Street called Nude “an explosion in a shingle factory.”3 This was by no means the only creative put-down hurled at Duchamp; Nude was variously described as “a lot of disguised golf clubs and bags,” “an assortment of half-made leather saddles,” an “elevated railroad stairway in ruins after an earthquake,” a “dynamic suit of Japanese armor,” a “pack of brown cards in a nightmare,” an “orderly heap of broken violins,” and an “academic painting of an artichoke.”4 Of all these, it was “explosion in a shingle factory”—linking together two particularly modern things, explosions and factories—that stuck and is often used to refer to Duchamp’s painting even today.

While it was the work that got the single most attention, Nude was not alone in drawing heat. The New York Times opened its review of the Armory Show with a few obviously rhetorical questions:

What does the work of the Cubists and Futurists mean? Have these “progressives” really outstripped all the rest of us, glimpsed the future, and used a form of artistic expression that is simply esoteric to the great laggard public? Is their work a conspicuous milestone in the progress of art? Or is it junk?5

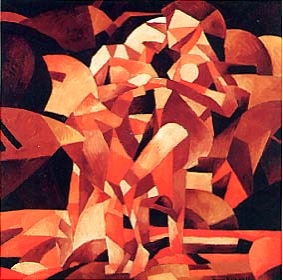

Francis Picabia. Dances at the Spring, 1912. Oil on canvas; 47 7/16 × 47 1/2 inches (120.5 × 120.6 cm) © Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Readers wrote to local and city papers, calling the art “nonsense” and declaiming its “amorphous conceits.”6 Gertrude Stein, as a champion of some of the most reviled art, came in for a drubbing many times. One writer complained that Stein’s criticism sounded like a drunk “who is suddenly called upon to make an after-dinner speech.”7 The Chicago Tribune published this poem:

I called the canvas Cow with cud

And hung it on the line,

Altho’ to me ’twas vague as mud

‘Twas clear to Gertrude Stein8

Theodore Roosevelt, then President of the United States, attempted to be evenhanded, writing in Outlook magazine, “The exhibitors are quite right as to the need of showing to our people in this manner the art forces which of late have been at work in Europe, forces which cannot be ignored.”9 After this brief nod of approval, he went on, “This does not mean that I in the least accept the view that these men take of the European extremists whose pictures are here exhibited.”10 In other words, Americans should keep track of the European avant-gardes, but by no means approve of them.

During the month Nude was on view, hardly a day went by without a story about the Armory Show appearing in the press. As a result, attendance swelled. Numerous writers could not help but compare the show—and whatever you think of the art, you cannot deny a certain aptness in the comparison—to productions by P. T. Barnum. The Armory Show became a circus.

On March 29, 1913, two weeks after the show closed, The Literary Digest published a collection of letters to editors around the country under the title, “The Mob as Art Critic.” [PDF] Some of the letters are astounding, if only in terms of the amount of energy people were willing to put into them. One man, claiming to be a scientist, worked his prose into brilliant contortions, fuming about the scientific language used by artists and critics favoring Cubism. He wrote:

These “sensations” we hear about “reproducing” are impossible of reproduction—even in the mind, still more on canvas—for when they are gone they are gone forever. What takes their place is not a sensation at all but a memory, and a memory is not a sensation. The sensation experienced upon being outside of a good dinner is gone, and it can not be reproduced by remembering it (nor painting its portrait), luckily for cooks. And just as a memory of the sensation—or “thrill”—of a dinner presents none of the satisfactions of the sensation itself, neither do the memories of any other sort of thrills.11

Georges Braque. Violin: “Mozart/Kubelick,” 1912. Oil on canvas; 18.1 × 24 inches (46 × 61 cm). Private collection.

The supreme irony of the passage is that, with its incoherent insistence and repetition and recoding of familiar nouns, it ends up sounding a lot like a poem by Gertrude Stein. The phrase, “What takes their place is not a sensation at all but a memory, and a memory is not a sensation,” could well have come straight from any of Stein’s most impenetrable texts (for example: “You are extraordinary within your limits, but your limits are extraordinarily there”12).

One concerned citizen was kinder to the scientific language being used to describe this modern art. In fact, she thought the art should be renamed “sensationalism . . . not in the popular sense, but in the scientific application of the term.”13 She went on:

For these artists are endeavoring to give a pictorial representation of the physical reaction to sense stimuli, the cellular and nervous reactions which carry the messages of sense perception to the brain. They attempt to diagram the shiver which indicates to you that you are cold; the nerve shock and accelerated heart action which mean fear.14

While she granted there was skill involved, she ultimately thought the art should be “more appropriately placed in the lecture-room of a professor of psychology than in an art-gallery”; her ultimate complaint, in the form of a question, was, “But is it beautiful?”15 She thought not. That question would be echoed eighty years later, in 1993, when CBS ran an infamous j’accuse against the contemporary art establishment in a 60 Minutes segment called, “Yes . . . But Is It Art?” The title of segment not only played on widespread public suspicion of the arts (most people would answer, “No, it is not”), but also recalled the ontological vertigo that had overtaken the art world around the time of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), an industrially produced urinal he re-christened as an art object.

Coming at a time when the National Endowment for the Arts was gearing up to battle Congress for its very life, that episode of 60 Minutes touched a nerve both in the art world and outside it. America was fed up with contemporary art, and contemporary artists, for their part, were fed up with America. People had drawn the battle lines back in 1913, with the reaction to the Armory Show.

But the story is more complicated than that.

Something interesting happened in the art world during the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s. The Surrealist concern with the articulation of psychologically repressed desires—such as violent sexuality and sexualized violence—developed into a widespread concern with the articulation of systematically repressed identities: queer, black, Chicano, bisexual, transgendered, diasporic, postcolonial, and so on. The reaction to this art—art that embraced what came to be called “identity politics”—was of a different nature than the reaction provoked by the Armory Show. Many critics during the culture wars actually used formal incomprehension to mask a greater understanding of a work’s real meaning. Critics of, say, queer art did not fundamentally puzzle over what they were looking at. And this is where we are today.

The virulent homophobia unleashed on the National Portrait Gallery’s Hide/Seek exhibit by the Cybercast News Service last November is an illustration of how much the debate about art has changed in the past hundred years. In some ways less insular, contemporary art is also less insulated from the day’s most divisive issues. It feels almost quaint to look back on a time when what angered people about art was that it violated the rules of perspective and of the unity of time and place, or that it unbound color from object. If these battles weren’t always pretty—for they were frequently fueled by class resentment—they still seem, relative to contemporary circumstances, somewhat bloodless.

1. Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985).

2. Milton W. Brown, The Story of the Armory Show (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988), 43.

3. Brown, 137.

4. All quoted ibid.

5. Kenyon Cox, “Cubists and Futurists Are Making Insanity Pay,” New York Times, March 16, 1913, VI, 1.

6. “The Mob as Art Critic,” Literary Digest 46, no. 13 (March 29, 1913): 708.

7. Robert Tuttle Morris, Microbes and Men (New York: Doubleday, Page, & Co., 1915), 261.

8. All quoted in Brown, 138.

9. Theodore Roosevelt, “A Layman’s Point of View,” The Outlook, March 29, 1913, 718.

10. Ibid.

11. “The Mob as Art Critic,” 708.

12. Gertrude Stein, Everybody’s Autobiography (1937; reprint Boston: Exact Change, 2004), 38.

13. “The Mob as Art Critic,” 708.

14. Ibid.

15. “The Mob as Art Critic,” 709.

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published on Art21.org in November 2011.