Teaching with Contemporary Art

Teaching Through a Pandemic

Photo: Joe Fusaro

Looking back on almost a full year of teaching during this pandemic, I am beginning to recall what went well as much as what did not—or at least what was especially challenging. As I mentioned in my December 2020 article, the purposeful rethinking of our practice that continues as we navigate between forms of hybrid and all-remote instruction, has made us all new teachers again.

But when I take stock of what students have been doing, saying, and writing so far, there are some silver linings we can build on. Because the pandemic has forced teachers of all disciplines to reorganize and plan differently, it has affected the way we present ourselves as facilitators of the content and the way we engage students.

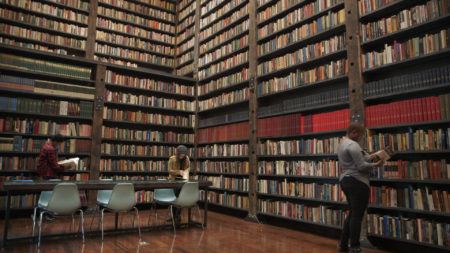

For example, the past year has seen a serious shakeup of the face that I present each day: what students literally see when they log in to our Zoom session. As often as possible, I try to make sure that the visual space I am in when teaching online not only serves the lesson but also gives the students a better sense of me as a person. Some days I will do a demo from our physical classroom, and some days I’ll be at home with easy access to books and resources that don’t always make the trip to school with me (and believe me, everything is not online). I’m even planning a lesson from my art studio, which students would normally not have the opportunity to see. This “face” extends to my online class webpages; now students engage much more often with this aspect of the course, so how I set up assignments and activities matters even more than it did before we were all teaching and learning online. Because I can’t be with students in their living rooms to explain my instructions, the content has to be clear and easy to manipulate, such as collaborative slideshows and discussion threads that are active for days or even weeks.

Photo: Joe Fusaro

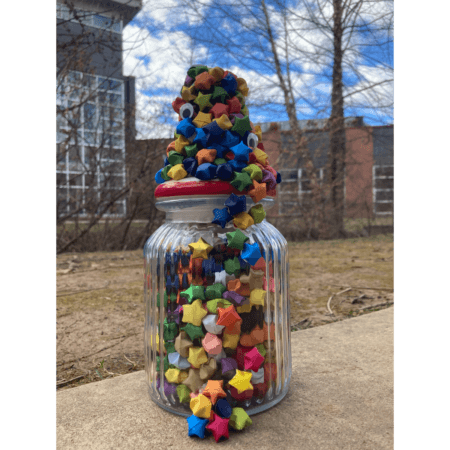

Another example I think about is the fact that students working online are sometimes digging deeper into the material than when we are together in the same physical space. Working on assignments at home, many students seem to be liberated from the pressure to perform in front of their peers, which they may feel when working in groups at large tables in the classroom. More often than I would have expected, students are developing insightful artworks that tell real stories about their lives; they are not simply completing assignments and utilizing stereotypical paths to the finish line. In some ways, this is a direct result of giving students more choices for participating in class. Some students are talkers, and some students are quiet writers who may express themselves in a paragraph, which may never make it to the shared physical space of a classroom with twenty of their peers. I continue to navigate a delicate balance of how students can take part in our evolving class community, noting that I’m learning more each day about the diverse ways that students can express themselves.

Looking back, I had two realizations that have become reminders:

Breakout rooms don’t have to be painful

If your school district allows breakout rooms, use them. All good teachers allow for small group discussions from time to time. It isn’t good for everyone to be in isolation during every class session. That’s crazy talk. Just like when we’re physically in school, the setup and expectations of what students will achieve in breakout discussions makes all the difference. For example, when I ask students to have a short discussion (10 minutes, usually) in breakout rooms, I make sure everyone understands that each person in the group should be prepared to share the major points of discussion. Students don’t get to choose their presenters, because we all know that, most of the time, the same students will be chosen to present. I choose different presenters each time or simply ask different students to post their notes, in order to build in more accountability.

Students need time to work together

In case we all need to be reminded: lecturing is still a bad thing. It’s better to mix up the way the class rolls out each day. For example, some days we talk, some days we write and reflect, and some days we make art and share our progress. Another thing I learned, with inspiration from my colleague Elcie, is that asking students to work while they’re online with me can be productive, as long as there are known expectations on the back end. When students are in a work session during my class, I try to make sure they have clear goals to shoot for. While they can work on an art project with their cameras off, all students must have their microphones on so that I can call on them, and all students must come back to the group at the end of class to reflect in some way on what was accomplished.

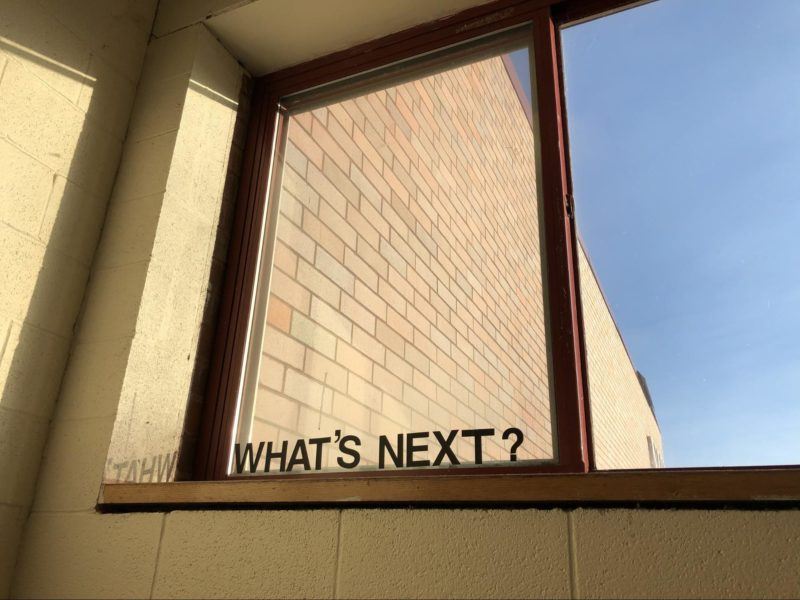

Photo: Joe Fusaro

As we continue to teach in a shifting and sometimes confusing landscape, it’s hard to find the bright spots, but they are there. And I wonder how our practice will change once we’re back in the classroom with our students again?