Teaching with Contemporary Art

Taking the Implicit and Making it Explicit

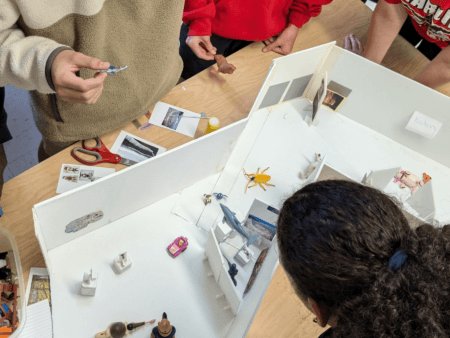

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Josephine Halvorson Gets the Conversation Going.” © Art21, Inc. 2014.

Name one instructional strategy you use to connect with students. In other words, how do you build relationships with your students?

This question was posed to my professional learning community with the Connected Arts Network through the National Art Education Association, and our answers were things such as: greeting students at the door, attending students’ extracurricular events, using students’ interests in projects, focusing on duty as time to connect with students, and getting involved in the community; the list could go on indefinitely. How many of those strategies would you write into your lesson plans? My guess is that not many of those relationship-building strategies would be written into lesson plans because, as art educators, we do them naturally. They are an intuitive part of artmaking and our teaching practice, so we don’t always recognize or name those intuitive moves we make as instructional strategies. But they are!

Our classroom instruction is also often intuitive and becomes a creative expression of ourselves. Because of the intuitive nature, there can be a few challenges. First, it can be challenging for us to explain the specific teacher moves we make to someone outside of the arts. Second, for someone with a general education lens, our classroom and creative instruction can be challenging to understand through observation. I recognize and acknowledge the incredibly unique lens I have as a general education-trained instructional coach with a visual arts teaching background. I’m not an administrator, coordinator, nor am I a classroom teacher. I’m a strange hybrid educator of sorts, and in my daily work I have the honor to work with all fine arts areas, including visual arts and performing arts. I share from this lens my personal reflection and experience.

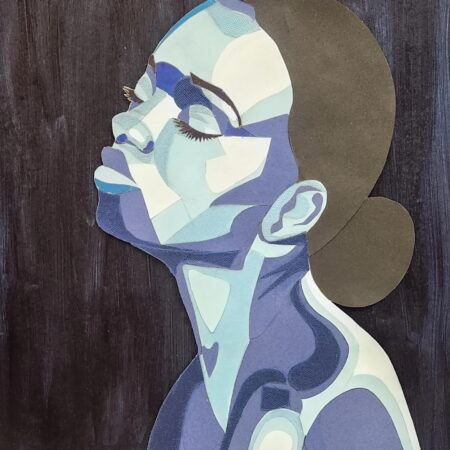

Production still from the Art in the Twenty-First Century Season 1 episode, “Identity.” © Art21, Inc. 2001.

Within arts education, we are constantly advocating for our fields and what we do. The intuitive approach to our creative instruction seems to span the fine arts disciplines; therefore, taking the implicit and making it explicit becomes a form of advocacy. By naming our intuitive moves using general education language and structures, we can provide entry points into our creative instruction. These entry points can help other educators connect with and recognize the instruction naturally happening in our classrooms.

However, entry points may land differently depending on the context. When collaborating with art educators, we can lean into intuition. But when speaking with other educators or administrators, leverage general education language and instructional resources to name what we’re doing in the art classroom. For example, instead of “creative process” or “artistic process,” which are more abstract terms and include lots of nuanced levels or steps, we might name the specific actions and skills learned within that larger process: ideation, discussion, rough drafts, editing and refining, or peer assessment.

Production still from the New York Close Up film, “Josephine Halvorson Gets the Conversation Going.” © Art21, Inc. 2014.

The idea of naming the intuitive actions is helpful when planning, too. Whether you start with the standards or an idea for the finished project, you’re starting with the student outcome. Working backwards from the outcome and listing the observable student and teacher actions can help name entry points. Here’s a sample with just a few actions listed for a landscape project.

- Outcome: Create a landscape painting. When sharing with other artists and leaning into intuition, we can understand all the teacher and student actions needed with the word “landscape.” We know there are multiple standards intertwined into every stage of a “landscape” project. However, someone outside of the arts might not have that natural understanding, so naming the teacher and student actions when lesson planning can provide natural entry points.

- Student Actions: Compare and contrast a variety of landscapes; learn and practice spatial drawing skills, learn and practice color theory and mixing paint, use and care for materials properly, spend time working on the project. These are a few examples of observable student actions. While it may seem unnecessary to list these out, if we do, it helps us to take the implicit and make it explicit.

- Teacher Actions: Curate examples of landscapes; facilitate a class discussion; demonstrate mixing paint; monitor student progress; provide feedback based on observation. Once the student actions are named, our teacher actions become clear. If students are going to discuss a variety of landscapes, then we will need to curate a collection of examples from a variety of artists and be prepared to facilitate the discussion.

With our actions named within our instructional planning, entry points into our creative instruction are also named. By naming the specific actions and skills, not only are we using language that a non-art educator might connect with, but we’re also breaking our process down into its specific steps, making the intuitive, implicit parts of our teaching more explicit and helping others to connect with what we do.