Teaching with Contemporary Art

Seven Strategies for the Studio Art Class

Many high schools offer introductory art classes, with names like “Studio Art,” “Art 101,” “Introduction to Studio Art,” or something similar. These courses often serve as the only art classes students take in their high-school career and, while some dismiss it as simply a step on the way to graduation, I think the studio art class can be both a place to get students more excited about taking advanced courses in subsequent years and a period of time that reinvents their understanding of the way artists think and work.1 As we move into a new school year, filled with big questions, political controversy, and a fair share of anxiety, here are seven strategies that help students to think and work less like compliant recipients, going through the motions, and more like artists.

1. Shift the Landscape

Allowing the classroom to become predictable works against art educators. Art is not a boring routine, so an art classroom should not be one either. Move around the furniture from time to time. Change seating arrangements. Create different groupings of students for activities and discussions. Make adaptability and working together in different ways the norm in the classroom.

2. Define Quality Together

Rather than provide students with the exact criteria for excellent scores, high grades, mastery, and so forth, build rubrics with the students in order to develop a shared definition of what constitutes high-quality work. Teachers should not abandon their criteria but rather should include students’ voices and give them a chance to “own” the criteria.

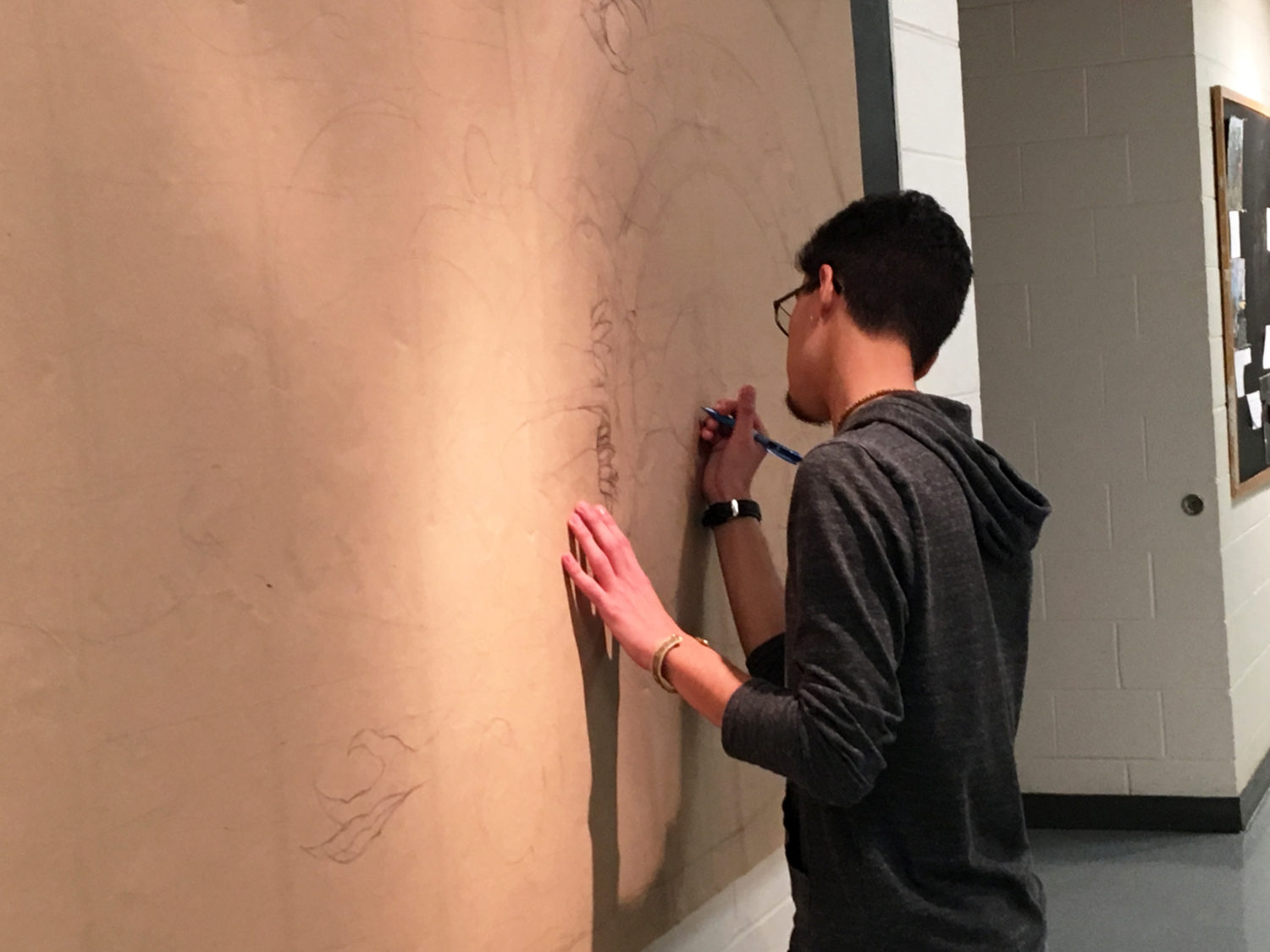

3. Make Process Visible

While sketching, planning, and brainstorming usually play large roles in studio art classes, often all of this work stays hidden. Find ways to make the planning visible: Share sketchbook samples. Post ideas and sketches for feedback. Create bulletin boards that track the process and are updated regularly. Conduct in-progress critiques of ideas rather than just critiques of finished products.

4. Do Two Things At Once

Most of us, if we have a studio or art-making practice, are usually working on multiple projects at the same time. Mirror this in the classroom by giving students multiple assignments, to be completed over longer periods.

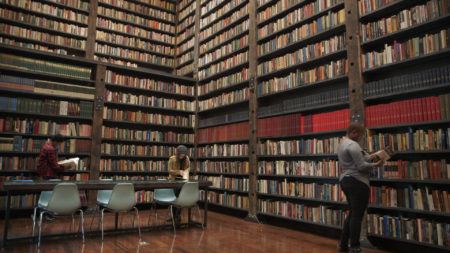

5. Provide Pathways for Research

When asking students to research a question, idea, or topic, provide pathways to find information that aren’t simply Google searches. As starting points, ask students to look at specific websites, artists, exhibitions, and collectives. Share your expertise and introduce artists and exhibitions that relate to the theme, idea, or question.

6. Ask Difficult Questions

One of the hardest strategies is probably the most rewarding. Asking difficult questions can provoke verbal and visual responses to important issues. When students are challenged to speak up and give voice to the ideas and issues they find critical and controversial, beautiful things can happen, even if they are not conventionally pretty. Think about the topics that are the elephants in the room in your school or community: how can this course provide a way to cast light on these issues and open discussions about them?

7. Revisit the Big Question

All good units of study are driven by a big question that students reinterpret throughout the lessons. But this question needs to be revisited along the way, and developing a collective response is important. Integrating the question that drives a unit of study in practical ways can often contribute meaningfully to students’ understanding .

1. Many states do not require an art class for graduation (see: Education Commission of the States, “Standard High-School Graduation Requirements (50-state).”