Sarah Ceurvorst (she/her) is an artist, educator, and activist based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. She believes that art can be a catalyst for positive social change and works to create that change within her communities. She has been a member of The Ellis School’s Visual Arts Department since 2015 and the Program Director for LEAP (Leadership, Excellence, Access Persistence) at Carnegie Mellon University since 2021. She previously worked with Contemporary Craft, Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, the Pittsburgh Office of Public Art, and Carnegie Mellon University’s SocialChange101 initiative. She also taught English language and visual art classes in Thailand as a Fulbright Scholar. She served as the board secretary of the Greater Pittsburgh Area Fulbright Association, a volunteer with the Son-Rise Program, a steering committee member of the Greater Pittsburgh Arts Council’s Pittsburgh Emerging Arts Leaders and a member of the University of Pittsburgh’s PRIDE Teacher Cohort. She is a member of Art21 Educators, where she works with a global network of educators and artists using contemporary art to address contemporary issues.

Teaching with Contemporary Art

Redefining Success

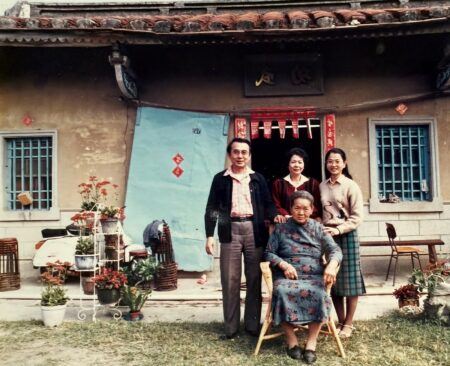

IMAGE: Photo courtesy of Sarah Ceurvorst.

How many of us feel stifled by the pressure to be seen as “successful”? This burden does not begin only when we enter adulthood. From a young age, schools teach children to strive for a narrow definition of success — get A’s on their report cards, sit still at their desks, and don’t make noise outside of recess. These restrictions on behavior, combined with limited conceptions of achievement, can lead even our youngest learners to sleepless nights, tearful moments in school hallways, and a constant hum of anxiety. In my first few years as an elementary art teacher, I saw kindergarteners break down over imperfect crayon drawings, first graders hit themselves because they didn’t immediately create realistic self-portraits, and fourth graders hyperventilate over “ruining” class projects with a few stray dabs of paint. Seeing my students beat themselves up this way broke my heart, not only because I cared about their emotional wellbeing but also because striving for perfection was not serving them as learners. Our education system’s pressure to be “successful” was not teaching students how to become curious thinkers or creative makers — it was training them to become docile, anxious workers with a fixed, scarcity mindset. My students’ struggles with perfectionism over process was keeping them from growing and developing an authentic love of learning.

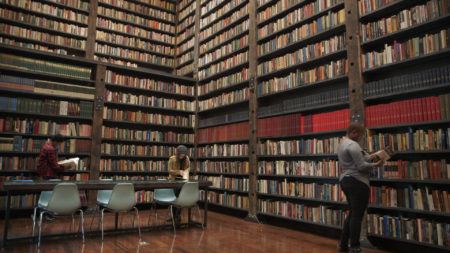

IMAGE: Photo courtesy of Sarah Ceurvorst.

I sought ways to relieve the constraints of “success” from my classroom. One of the techniques that helped alleviate pressure from my students was showing Art21 videos in class. By centering contemporary artists in their studios, students got to see examples of people who were redefining what success and achievement looked like for them. It provided powerful illustrations of how to accomplish your goals while disrupting cultural ideas of perfection.

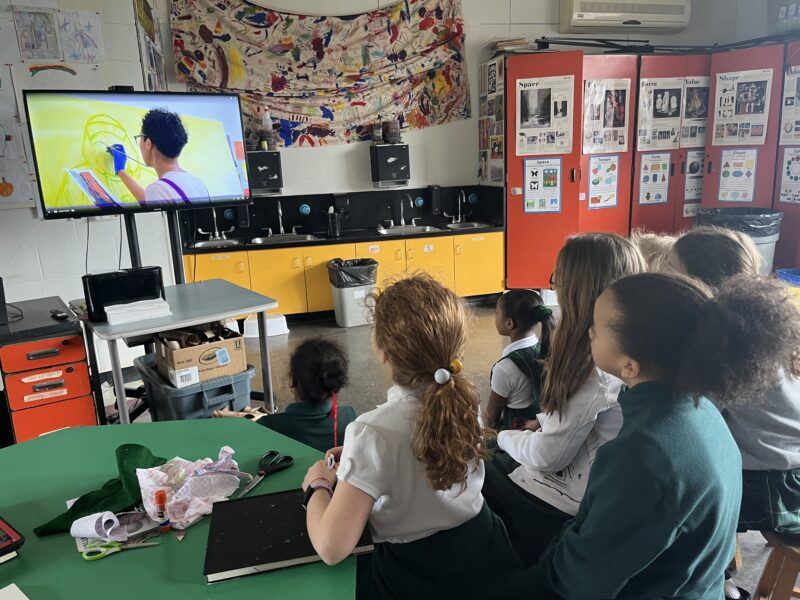

IMAGE: Photo courtesy of Sarah Ceurvorst.

In the beginning of my career, I only showed slideshows of completed works of art in my classroom. While I meant to inspire students with these images, the pristine walls of the gallery and the sleekness of finished products often came off as intimidating rather than approachable or relatable. When I started to show Art21 videos, students got to witness artists grappling with messy, complex challenges that arise in their studios. This reflected the challenges that my students faced in their own creative process. Through Art21 videos, they saw artists fumbling and making mistakes. We saw artists like Abigail Deville make work that’s messy and complicated, rather than pristine and exact. We saw Jaimie Warren and Matt Roche create their beautifully imperfect variety show, “Whoop Dee Do,” rather than a slick Broadway production. My students saw Alex Da Corte slipping and falling flat on his butt. Rather than be embarrassed, he celebrated the slip and made it a joyful moment. These artists experimented, failed, iterated, and talked about obstacles. This allowed me to drive home the message to my students that mistakes are part of learning and creating. Experimentation and failure aren’t the enemy of success — they are a vital part of it.

IMAGE: Photo courtesy of Sarah Ceurvorst.

Consistently sharing this message gave me the space to reevaluate and determine alongside my students what “success” looks like in my classroom. For us, a successful art class isn’t about having a classroom full of quiet students drawing realistic still lifes. For us, a successful art class can be messy, process-based, slow, emotional, vulnerable, chaotic, loud, joyful, and full of beautiful mistakes.