Teaching with Contemporary Art

Reciprocal Caretaking

Photo courtesy Tracie Dunn

Several years ago, my son was inspired by a beekeeper’s visit to his second-grade classroom and asked me if we could try this intricate hobby at home. I said yes and, several months later, following a surreal and fortuitous chain of events, our new agricultural endeavor qualified us to become caretakers for an old farmhouse, Wheeler-Harrington House in West Concord, Massachusetts. Estimated to have been built in 1742, this house had 276 years of experience before we were appointed to be its live-in caretakers and humbly stepped across its threshold. The house was erected before the American Revolution and was built entirely by hand for a young couple ready to farm the surrounding one hundred acres of land. When we moved in, I was prepared to put in the hours of work and patience necessary to preserve the structure and improve the premises. I did not, however, anticipate how quickly and deeply the experience would shape me.

Photo courtesy Tracie Dunn

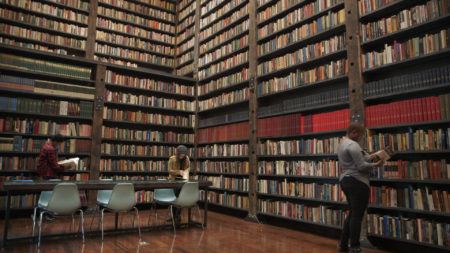

I first learned that hard work is the primary marker of a true caretaker. As an artist and educator, I naturally gravitate toward situations that require a great deal of energy and effort. I welcome opportunities that call upon thoughtful, resourceful, and imaginative problem-solving skills to bring about positive transformation, and this is how I approach my role as our home’s caretaker. I use my creative sensibilities to collaborate with the community that is responsible for the farmhouse, which is currently owned by the town and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Making decisions about the house requires documentation, communication, meetings, and coordination with town officials in order to determine how best to preserve it. While big projects such as fixing the roof may be outsourced, my partner and I are the ones who sweep the wide plank floors, keep an eye out for leaks, check the integrity of the foundation, and replace the old misshapen storm windows so the house can breathe. In the gardens, it is our hands that get pricked by the thorns of the antique roses and our fingers that pull rusty unidentifiable artifacts out of the dirt. We work long days (and take needed breaks) as the sun moves across the sky, listening to the birds and watching midday dragonflies turn into nightfall fireflies. We are part and parcel of this place. We brush up against its past generations while maintaining it for future ones. Being a caretaker has allowed me to experience a reciprocal relationship with a particular place. Our work benefits the house, and in return it nurtures us.

Caretaker life also demands having a new relationship to time. I imagine the home’s original inhabitants depended on ledgers, logs, journals, books, and communal knowledge to guide their efforts. In contrast, we do a quick Google search when we want to learn how to prune our peach trees or thin a raspberry patch, or we use Google to diagnose a chicken’s impacted crop and YouTube to treat it with a “crop massaging” tutorial (and she recovered within days!). Yet, we are still beholden to some of the same limitations shared by our predecessors. We are bound by the amount of work our bodies can accomplish in an hour, restricted to the length of a day, and accountable to the changing seasons. The frenetic speed of digital life is relinquished when caring for an old home and its surroundings, a fact I have learned to respect and value. This place insists that I temporarily suspend my busy life and commit to whichever task is at hand, assured that once it is complete, the next one awaits. My hands, often busy in the soil, quiet my chattering mind so that a deeper connection to slower rhythms becomes the foreground of my experience. I let the methodical and timeless labor restore me and bring a sense of connection and satisfaction. Patient care and work may be what are best for the house and, as it turns out, what are very good for me. Slowing down has helped me to foster a more peaceful relationship to passing time and brought me closer to this special place and its inherent cadence.

Photo courtesy Tracie Dunn

Routine work connects me to my environment and integrates me within a longer timescale. This sense of belonging was especially helpful this past spring, when the threat of COVID-19 forced us all to shelter in place. Families, mine included, were suddenly adapting to virtual spaces for work and school. It took a while for our household to create accommodations, and there were many times I cried from frustration. We were all feeling the stress arising from changing timelines and demands, unknowns, uncertainty, broken Zoom links, and glitchy Wi-Fi connections. We were grieving the loss of smiles and handshakes with acquaintances, of sharing time and hugs with loved ones. Whenever possible, we channeled that stress and anxiety into outdoor work; for me, it was the only way to stay mentally healthy. We spent long days clearing brush, repairing outbuildings, and generally taking care of the property, with a degree of energy and attention that would not typically be available to us if we were spending our days at work and in school. We reflected on how fortuitous it was to care for a historically significant property while major chapters in human history were being written. Taking care of Wheeler-Harrington House gave us a sense of purpose and safety during a time when we felt our world was weary and dangerous. With each effort we put into caring for the house, the house was also taking care of us.

Photo courtesy Tracie Dunn

There is no end to the work at Wheeler-Harrington House; as its caring custodian, I am immersed in a wellspring of tasks. Similar to when I enter the studio or classroom to get lost in a creative process, I feel at home in this place, where continuous work leads to surprising rewards and possibilities. Whether caring for a work of art, a student, a home, a loved one, or a stranger, my approach is the same. In the best situations, these experiences prove to be reciprocal. As a caretaker, I provide care to the best of my ability and, in turn, I grow and feel restored by the object of my care.

Photo courtesy Tracie Dunn