Deep Focus

Polyculturalist Visions, New Frameworks of Representation: Multiculturalism and the American Culture Wars

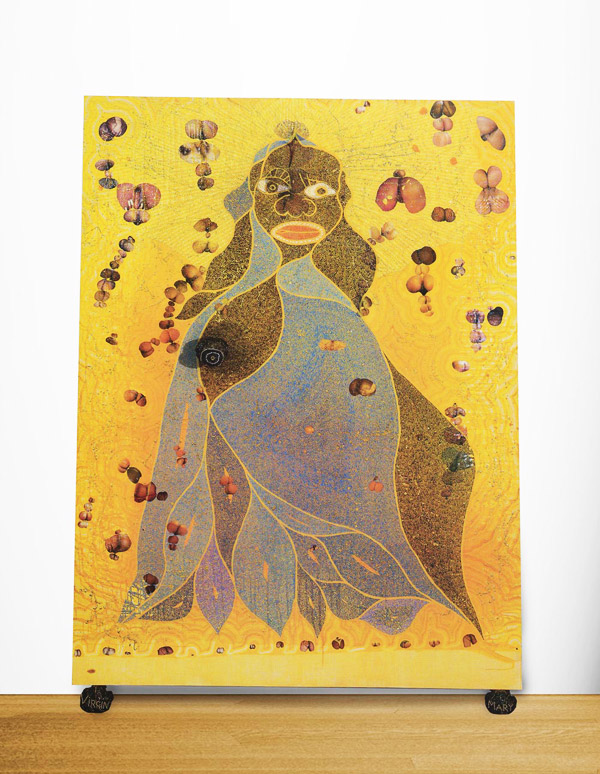

Chris Ofili. The Holy Virgin Mary, 1996. Courtesy of The Saatchi Collection.

Culture wars are intellectual, political, religious, and/or social conflicts over cultural pluralism in Western societies. Culture wars have polarized Americans over social issues such as race and representation, education, and, most importantly for this essay, multiculturalism. In the United States, multiculturalism can be traced historically to the civil rights movement in the 1950s and ’60s. Following several decades of migration and immigration, multiculturalism then intersects with the culture wars of the 1980s and ’90s. Jeff Chang argues that the “aesthetics of multiculturalism transformed American and global popular culture,” continuing to say that the battles waged in the art world and beyond were “less celebrated, but the victories of the multiculturalism movement here were far more decisive.”1 The notion of multiculturalism, as an issue inflaming the culture wars, has taken several turns over the years. This essay highlights several high-profile art exhibitions as sites of controversy, thereby examining the ongoing crisis of representation in cultural institutions.

Multiculturalism offered a distinct culture war fought over issues of exclusion and identity politics. The conservative climate in the United States government during the 1980s and 1990s set the stage for a series of battles concerning the position of underrepresented minorities in the arts. In the 1980s, emerging artists of color were trying to define a new aesthetics of representation. Chang describes this time as one of “creative ferment taking place in the avant-garde and in communities of color, where underground networks of galleries, theaters, nightclubs, and performance venues were fostering art defined by racial pride and militancy.”2 In tandem with these creative acts, artists and activists also protested in galleries and on college campuses across the country. Cornel West argued that multiculturalism amounted to nothing less than a “new cultural politics of difference” in which the impulse was to “trash the monolithic and homogenous in the name of diversity, multiplicity, and heterogeneity.”3 In other words, West was anticipating a society composed of diverse representations, realities, and points of view.

Fast forward to 2010, when Robin Pogrebin’s article, “Brooklyn Museum’s Populism Hasn’t Lured Crowds,” criticized museums for lowering their standards to create more diversity. For me, this editorial called the underrepresentation of minorities in the arts into question, asking: How can and should we address cultural issues in institutions? I am opposed to multiculturalism, not for the reasons given by cultural conservatives, who want to preserve a certain institutional standard, but because I am not certain that it achieves the racial harmony to which it aspires. Multiculturalism has been problematic in its divisiveness; after all, it does not necessarily reflect the way cultures influence each other. In fact, a number of cultural institutions are actively reconsidering the stakes of the term since it was first articulated decades ago. In what follows, I present a chronology that reflects the continual evolution of the movement, particularly through artists’ advancements in technology.

On September 23, 1999, New York City Mayor Rudolph Giuliani issued his first critique of the Sensation exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. Featuring work from British millionaire Charles Saatchi’s personal art collection, the exhibition sparked controversy over Christopher Ofili’s work, The Holy Virgin Mary (1996), a painting of the Virgin Mary made in part out of elephant dung. Giuliani declared the work to be “insulting to Catholics,” adding that there “is nothing in the First Amendment that supports horrible and disgusting projects,” and that “if you’re going to use taxpayers’ dollars, you have to be sensitive to the feelings of the public.”4 Norman Siegel of the New York Civil Liberties Union came forth with a warning: “Once the government, using public funds, punishes artists to suppress unpopular views, we are heading down a dangerous First Amendment road.”5 Meanwhile, Hillary Rodham Clinton and the City’s Cultural Institutions Group sided with the museum. Six days later, the U.S. House of Representatives proposed prohibiting funds from being used for the Brooklyn Museum unless the Museum immediately canceled the exhibition, which contained pornographic images and other examples of religious blasphemy, in addition to Ofili’s painting. Eventually, a judge ordered that the City restore the funding denied to the Museum and stated that, “The City has now admitted the obvious; it has acknowledged that its purpose is directly related, not just to the content of the exhibit, but to particular viewpoints expressed.”6 Sensation came to a close at the Brooklyn Museum during the first week of January 2000. However, its impact is still felt more than a decade later.

Well-known battles such as Giuliani vs. Brooklyn Museum mask an even more pervasive, ongoing conflict concerning representation in cultural institutions. Twenty years prior, Artists Space, an alternative art gallery also in New York City, was the focus of political ire in the late 1970s. The gallery presented Donald Newman’s exhibition, The Nigger Drawings, which raised concerns over racism and public accountability in artistic production. Newman, a young white male artist, commented that he had been “niggerized” by being forced to show at a non-commercial gallery.7 Public outrage over the exhibition’s title and the artist’s comments helped spawn the Emergency Coalition, a group of minority and feminist artists. Their activities included a letter-writing campaign to the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA), which, along with the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and other financial sources, supported the gallery. The Emergency Coalition asserted that the exhibition’s title was a “blatant expression of the racism operating within the art world,”8 a factor that was generally apparent only if someone stepped back to notice the systematic exclusion of minority artists from exhibitions. The numbers spoke for themselves: between 1980 and 1987, of all exhibitions in New York City’s major cultural institutions, 87.75 percent featured white artists.9

As a result of the Newman exhibition, the NEA’s visual arts program director called a meeting of the Emergency Coalition. Sculptor Camille Billops, who was one of the Coalition’s thirty artist members, pointed to the need for the ongoing monitoring of arts policy and argued that, “Freedom [does] exist in the studio, but once you go into public space, it’s different. If you submit a painting to the Guggenheim that doesn’t agree with their policy, it doesn’t go on the wall.”10 A transcript of “Got Next: A Roundtable on Identity and Aesthetics after Multiculturalism” examines the aftermath of controversies such as Newman’s show at Artists Space and Giuliani vs. Brooklyn Museum. According to journalist Greg Tate, this same moment in the late ’80s and early ’90s was also “when dialogues around multiculturalism and diversity become very prominent [. . . and] when people are in reaction, in resistance to Reagan, and, in New York, to Giuliani.”11 Conflicts with multiculturalism intensified in the mid-’90s, along with the hope that the art of underrepresented minorities would emerge from the streets and alternative galleries to gain critical momentum. But other, more powerful forces were gathering at the same time to challenge this movement.

In the Fall 1989 issue of High Performance, performance artist Guillermo Gómez-Peña wrote:

“[Multicultural] is an ambiguous term. It can mean a cultural pluralism in which the various ethnic groups collaborate and dialog with one another without having to sacrifice their particular identities and this is extremely desirable. But it can also mean a kind of Esperantic Disney World, a tutti frutti cocktail of cultures, languages and art forms in which ‘everything becomes everything else.'”12

By the 1990s, multiculturalism had become an all-purpose word that evoked a range of meanings and implications. For some, it meant resources (such as curricula) and for others (like Gómez-Peña), it was a fad that never lived up to its promise as a political movement for underrepresented minorities and women. The trouble seemed to be that multiculturalism had been commodified, its potential as political force diluted. Multiculturalism became a bandwagon of opportunity aboard which everyone jumped, from education (broadly) to the art establishment to the conservative right, who utilized the movement to abolish affirmative action legislation (such as California’s Proposition 209 in 1996).13

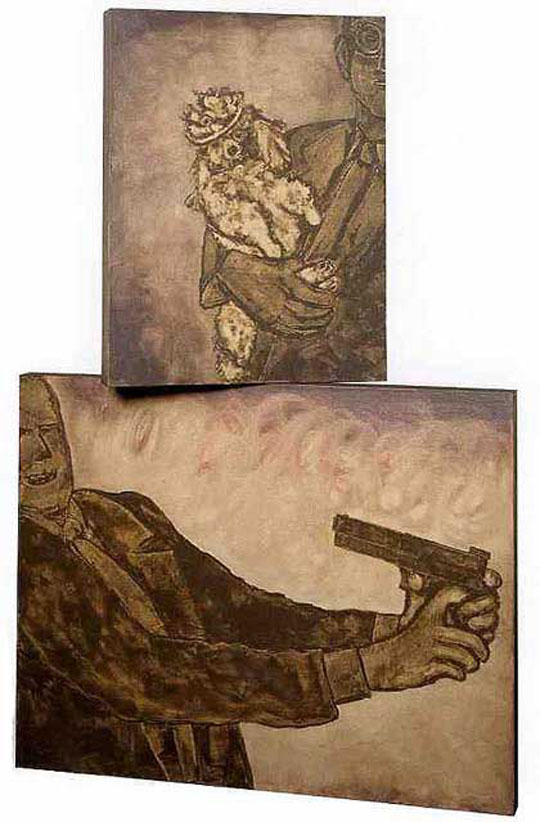

Ida Applebroog. Marginalia (dog with hat), 1994. Photo by Dennis Cowley. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

A version of Gómez-Peña’s treatise on multiculturalism was included in the official catalogue for The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s (1990), which focused on the decade’s identity politics. Featured works came primarily from emerging artists of color and feminist artists—including Martin Puryear, Nancy Spero, Ida Applebroog, and Alfredo Jaar—who were trying to define a new aesthetics of representation and to counter (white male) hegemony. By the mid-1990s, the multiculturalist movement had hit its peak; activists and artists decried white privilege while expanding marginalized peoples’ representations in cultural institutions. We can locate multiculturalism’s true apex in the 1993 Whitney Biennial, which one reviewer praised as an “explosive self-examination shaking American society” while another dismissed it as implying “cultural reparations.”14

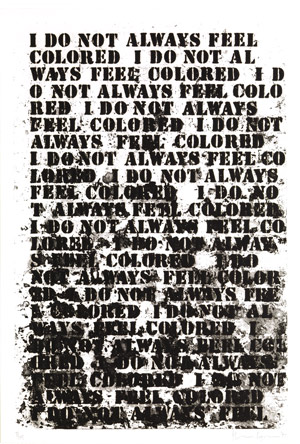

Glenn Ligon. I do not always feel colored, from Untitled series, 1992. Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of The Peter Norton Family Foundation.

Throughout the 1990s, multiculturalism was widespread in popular culture and education, in part through the contributions of artists of color. Highly charged texts, emotional conversations, and traumatic memories were prevalent themes in the work of artists of color during this time. Glenn Ligon historicized the language of self-description to draw out the trauma, but also the ironies, of modern black experience. For example, in his work, I do not always feel colored (1992), he repeats a quote from an autobiographical essay by Zora Neale Hurston [PDF] over and over until it verges, through the force of excess oil paint, on illegibility. Pepón Osorio‘s Badge of Honor (1995) becomes a site for a healing dialogue between an estranged father and son. Ligon, Osorio, and feminist artists such as Ida Applebroog were part of a multiculturalist explosion that brought issues of race, gender, and representation into the mainstream. As the ’90s came to a close, multiculturalism was considered on the whole to be a useless cliché. Meanwhile, there was a new wave already on the way, ready to challenge the status quo, achieve gains for underrepresented minority and feminist artists, and reconsider the meaning and scope of the movement.

Pepón Osorio. Badge of Honor, view of father’s cell, 1995. Photo by Sarah Welles. Courtesy of Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York.

The decline of the multiculturalist movement began in the late ’90s and continued into the first decade of the new millennium, alongside the rise in cultural conservatism. Then, with the election of Barack Obama came a general sentiment (as in ideas of “post-race” and progressive views) that it was the beginning of the end of the culture wars and of multiculturalism by association. However, the rhetoric of cultural warfare disguises the fact that American and Western societies are still deeply divided along lines of race, class, and gender. Rod Dreher opines that, “The culture war will never die, only wax and wane across multiple battlefields. When you live in a large, diverse, pluralistic democracy, it comes with the territory.”15 Multiculturalism, which celebrated cultural plurality, has arguably become less relevant as a movement, yet the social conditions that produced the movement persist. For example, Arizona governor Jan Brewer signed into law a resolution to ban ethnic studies in 2010.

Carrie Mae Weems. Looking Forward, Looking Back, from Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment, 2008. Courtesy of the artist.

Carrie Mae Weems‘s work, Constructing History: A Requiem to Mark the Moment (2008), enlisted students in a series of photographed scenes set on a theatrical stage. Weems notes that this project began and ended with Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton. In an interview with Art21, Weems explains: “In one moment, there was an enormous shift in the American imagination—African-Americans who had never considered this to be home, this to be a place that represented them—suddenly said ‘my country’ and ‘my president.'” Weems, having fought her own battle previously with the Harvard Archive over her appropriation of archival photos of slaves, signals the coming of a wave of artists who are addressing identity, race and representation, and their relationship with institutions on their own terms. Whether in a museum, gallery, or university-based site, artists of color are finding new ways to successfully navigate these structures, including on the Internet.

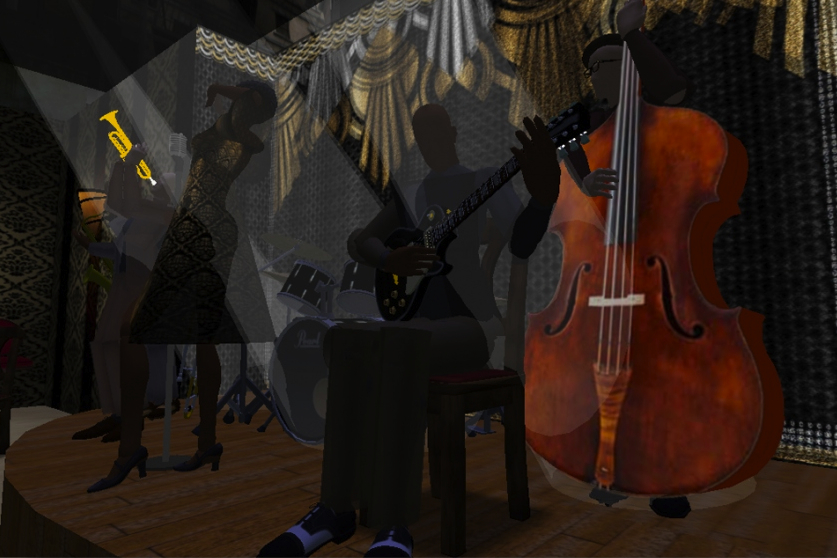

Philip Mallory Jones. The Paragon Show Lounge from Bronzeville Etudes & Riffs, 2011. Courtesy of the artist.

Philip Mallory Jones, whose video installations were included in The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s at the New Museum in 1990, is part of a growing number of artists who reflect a world that has extended beyond traditional borders and, through the advancement of the Internet, have reached broader audiences, moving from coalitions to exhibitions and events based on common affinities. Jones’s most recent work, Bronzeville Etudes & Riffs, is set in the virtual three-dimensional world of Second Life and is, in his words, “populated by character avatars (both live and scripted), interactive objects, and dramatic tableaux.”16 Chinese artist Cao Fei‘s RMB City Opera highlights a virtual three-dimensional cityscape that allows viewers to enter the simulation and experience interaction as actors on a stage and as avatars in a virtual world. Cao Fei describes RMB City as a virtual city that “is imaginative, with no nationalities or borders.”17 Fei is part of a younger generation that has “fully adopted digital media and embraced popular consumer culture and all things global, diverse, old, new, intellectual and non-intellectual.”18 The museum notes this generation’s prolific use of computers, cell phones, and social media “to challenge the political system by simulating it first.”19

Multiculturalism has been one of several battleground issues, so much so that recently there has been an institutional reconsideration of the term. The New Museum’s publication, Rethinking Contemporary Art and Multicultural Education, points to the problematic correlation between the art of the 1960s and ’70s and the multicultural work that then emerged in the late 1980s and ’90s. Cultural critic Vijay Prashad argues that multiculturalism is divisive and advocates for a “polyculturalism,” which views the world as “constituted by the interchange of cultural forms.”20 In a sense, this has liberated the work of artists of color, setting it free in multiple modes of discourse, such as globalism, transnationalism, and virtual three-dimensional environments where identities can easily be transcended or exchanged. In our age of accelerated technology, artists can move culture, capital, and ideas between worlds.

Race and representation remain critical issues for consideration, in part because of ongoing battles concerning the relationship between culture and institution. However, with the threats to net neutrality and huge federal budget cuts looming in 2011 for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, the NEA, and the Arts in Education program, we must realize that this evolving post-multiculturalist movement is not just about winning the battle but also about winning a war. Once again, we have state-level campaigns bankrolled by conservative foundations that now threaten public workers, especially teachers. Thirty-plus years of battling for inclusion in the arts and the adoption of new technologies have given us tools from which to turn back the conservative tide against the public sector for the betterment of America. Art is political in that it produces new knowledge that can serve as a basis for changing the world. In the spirit of multiculturalism and now polyculturalism, artists can present policymakers and influential institutions with new possibilities and modes of understanding art and culture for the inclusion of all.

1. Jeff Chang, “On Multiculturalism: Notes on the Ambitions and Legacies of a Movement,” GIA Reader 18, No. 3 (Fall 2007), https://www.giarts.org/article/multiculturalism.

2. Ibid.

3. Cornell West, “The New Cultural Politics of Difference” (1990), https://www.bobbybelote.com/!!teaching/Readings/WestDiffrnce.pdf.

4. “Sensation: Young British Artists from the Saatchi Collection” (July 20, 2000), https://www.artnotart.com/f-sensation.html.

5. Ibid.

6. Ibid.

7. Chang, “On Multiculturalism.”

8. Jacqueline Trescott, “Minorities and the Visual Arts: Controversy before the Endowment,” Washington Post, May 2, 1979, B7.

9. Leo Segedin, “Making It: Race, Gender and Ethnicity in the Artworld,” January 26, 1993, https://www.leopoldsegedin.com/essay_detail_making.cfm.

10. Trescott, “Minorities and the Visual Arts.”

11. Jeff Chang, Total Chaos: The Art and Aesthetics of Hip-hop (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 2007), 35.

12. Guillermo Gómez-Peña, “The Multicultural Paradigm: An Open Letter to the National Arts Community,” High Performance 12 (Fall 1989): 26.

13. Angela Davis and Neferti X. M. Tadiar, Beyond the Frame: Women of Color and Visual Representations (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 40.

14. Chang, “On Multiculturalism.”

15. Rod Dreher, “Obama Won’t End the Culture Wars,” Real Clear Politics, February 16, 2009, https://www.realclearpolitics.com/articles/2009/02/obama_wont_end_the_culture_war.html.

16. “Bronzeville Etudes & Riffs,” Philip Mallory Jones website, accessed April 20, 2011, https://philipmalloryjones.com/bronzeville-sketches.

17. “RMB City Opera by Cao Fei,” Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, accessed April 20, 2011, https://www.nelson-atkins.org/art/exhibitions/rmbcityopera.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Vijay Prashad, Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting: Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity (Boston: Beacon Press, 2002), 67.

Editor’s note: This essay was originally published on Art21.org in 2011 as part of “The Culture Wars Redux,” the inaugural installment of Ideas, a precursor to the Art21 Magazine‘s bimonthly thematic issues.