In the Studio

Tom Burr revisits, reflects, and thinks anew.

Robert Sandler – I thought we could start with where you are right now and how you’re spending your time.

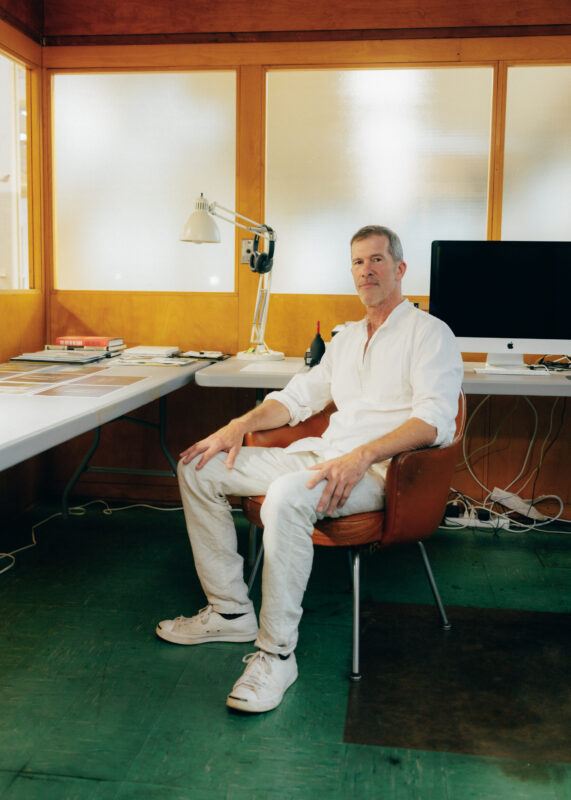

Tom Burr – At the moment I’m in Torrington, Connecticut, which is where I have a large space that I have termed The Torrington Project. Torrington is an old factory town that sprung up a bit later than some of the older colonial towns surrounding it in Litchfield County. The architecture is very warm that way, familiar in terms of its history—which is exactly why I didn’t want this kind of architecture. But then I realized that’s actually brilliant, how you often find yourself attracted to that thing that you were saying you couldn’t have.

Maybe it’s simply out of urgency that it came into being, but it’s, in some respects, a classical studio space where I can work and produce new work and think about my work. It’s also something of a living archive, a consideration of works that I have done from the ’90s to the recent past, where I can see certain works in proximity to one another, consider them again, think about them anew, and also take the reins with regard to what their fate might be.

What spans this living archive?

There’s a small group of works that I’ve always kept to myself. These are from 1988, 1990, early ’90s, during a period when I was showing in group shows primarily in New York. Those are some of the earliest things here.

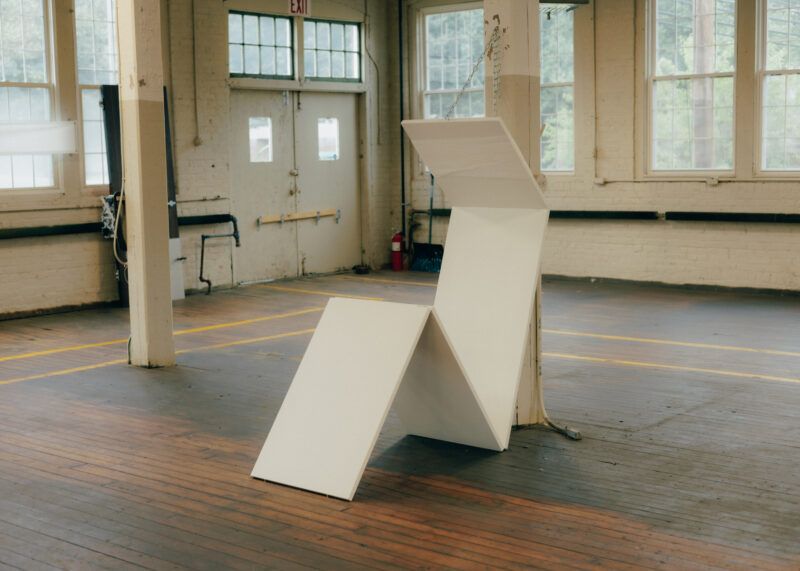

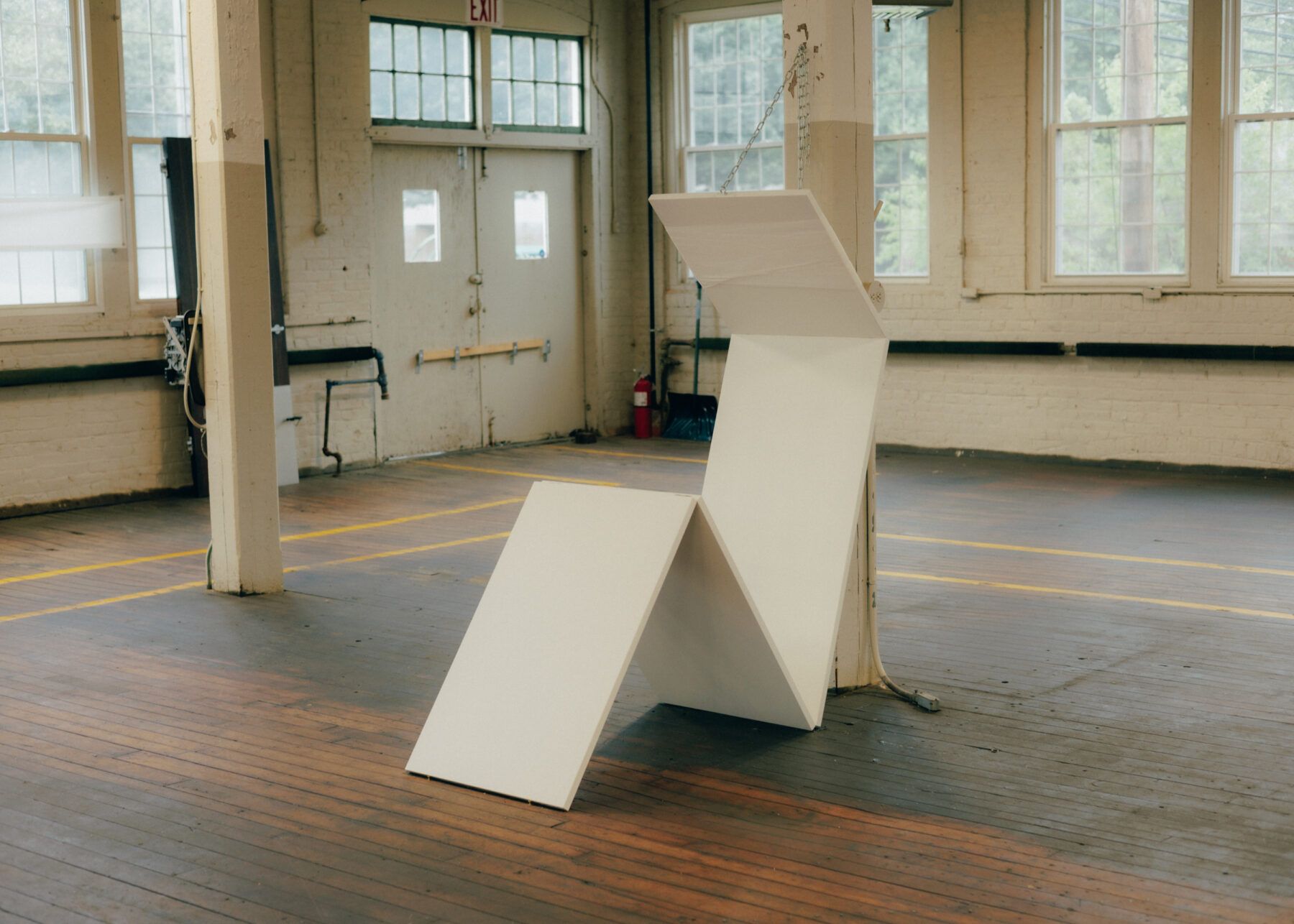

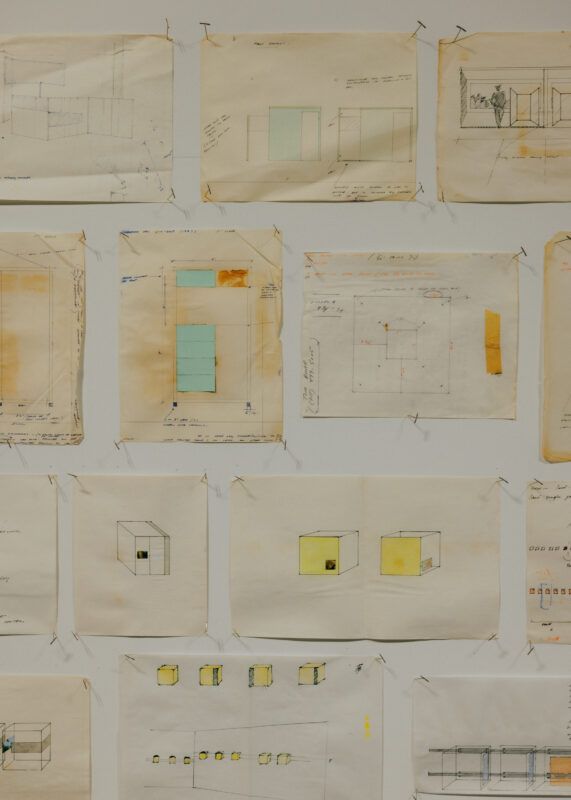

And then there are works such as Container 1, 2, 3 (2000-2001), which was made for an exhibition in Berlin. After the exhibition, the works were dismantled because it was too complicated to store them. So those works kind of slipped out of my consciousness to a certain degree. Other works from that same time period, Deep Purple (2000), went on to become very strong markers in the arc of what I’ve done and wanted to do. And this piece [Container 1, 2, 3] felt lost. It was something that I wanted to ground the space in. Whereas there might be other works that have the tendency to come and go, that’s one work that’s going to be here for the duration of the project and is to some degree part of the architecture—where I placed it determined the placement of other things.

What have you noticed in revisiting these works?

Everything that I was thinking about at that time, the erosion of public space, the erosion of different publics’ use of urban spaces, those issues have been largely resolved in terms of the privatization of, let’s just say Manhattan, which I think is indicative of any number of places. So there’s power in a certain way that the works have, of having been time markers—time capsules that detonate over time. And this is something that I thought about at that moment, though I certainly didn’t have any experience with it—but I always imagined that works would release certain elements, certain layers of their sedimental makeup.

Bringing them together here though, for me personally in a kind of subjective realm, here in the space—there’s all sorts of parallels to my own body and aging and time passing, so there’s this innocence that I see connected to certain earlier works that I find ravishing. And I see these early moments of positions that I took, quite consciously, as one does, particularly when you’re younger, trying to stake out certain kinds of territory. And I was doing that through actual territory and earth art and the history of landscape, painting as well.

What’s an example of the kind of innocence that you’re admiring?

I think there’s something, I don’t know … charming. I mean, I recognize that it’s me and I’m saying this, but it’s also me a long time ago—this incredible love affair that I had with certain artists and continue to have. Now, I frame it quite differently.

At the time, I was very enamored of this generation of figures from Robert Smithson to Eva Hesse to Adrian Piper, these larger-than-life figures to me. And my only way to engage with them was to reference them. I think that came out of the extraordinary tools that were given to me, largely through feminism as it intersected with a fraction of the art world, the idea of appropriation and sort of a naturalized position—where you would take up almost a kind of camouflage and/or drag. I think that started to become very resonant for me.

It seems that speaks to a tension that your work operates within, one between the formal and the personal.

When I was working with these works in the early ’90s, I was thinking about speaking from a particular subject position. I was thinking about my own coordinates, but I was doing so in a veiled way so that I could almost hold up a mirror to a situation and take up some of the tropes of a documentary position. I was also trying to create a very, very strong formal language at the same time. That was always important to me, that this content—these issues, these subject matters, these references, these bits of information and facts—would also get mixed up with a formal language that was similar to some elocution, when somebody speaks in a certain way and there’s an annunciation that takes that language a little bit above itself. Formalism and playing with form was a way to not accept any of the neutral tenets that I had come to learn regarding conceptual art, for instance, none of those assumed neutralities.

What it was like to make work that resists a kind of individual subjectivity at the height of the AIDS crisis?

With that crisis came a need, I think, to essentialize by the political movement to some degree. There wasn’t time to pick through the nuances, but I still wanted to do that. I felt that that had political import, that’s where my politics were lodged. At the time, to represent gay male subjectivity was simply to show the body more often than not, whether it was the ravaged body or it was the muscular, iconic body. And that largely eclipsed any other kind of imagery, certainly eclipsed any more gender-fluid bodies, any lesbian bodies. It was very dominant, this kind of notion. It was used throughout club culture, but also throughout AIDS politics to a certain degree. I wanted to try to not work against that at all but use that environment to dig deeper, to layer deeper. I was extremely conscious of trying to not work against, in the moment, any kind of politics that I needed for what I wanted to say. So my instinct was to make work that was as multifaceted as possible. And I think one of those facets was trying to question essentialism or essential subjectivity at all.

But then there was a shift. There were many shifts, but as I made work over time, people increasingly tried to find me in the work. There was a literalness that people assumed relative to issues I was speaking about, and I was interested in that, but I was also interested in decoys and where I could be there and where I couldn’t be there. I didn’t want my work to look in a predetermined way political, in a predetermined way conceptual, in a predetermined way known. I wanted to use some sort of concept of schizophrenia, of inner conflict, of dualities, of multiplicities of self, different voices.

In 2017, you created an exhibition, Body/Building, in Marcel Breuer’s Pirelli Building in New Haven, Connecticut—your hometown. As part of that project, you gave tours of the space, and these tours became something of a social event. How do you view the relationship between gossip and art?

I love and believe in the idea of gossip and tangential stories and anecdotes that hover around works. You don’t always have to have them present in the works. They filter through the life of the work over time. All the important works that I ever saw, I thought about when I was young, came through knowledge, came through texts, came through hearsay, came through other people telling me about them. Very few of our important aesthetic experiences early in our lives are one of a direct relationship with an artwork.

It seems that the Torrington Project shares something of this indirectness. It extends the art across different repetitions and relations.

It’s only now, and that’s why The Torrington Project is so resonant for me, that I have the luxury, if I can use that word, of being able to look at these different iterations as important moments. Which isn’t to say I had any kind of extraordinary foresight to be able to plot it out in any way, but I always had a strong desire to see things connected one to the other to the other to the other to the other—and to see accumulation, to see residue taken forward. In this final phase, I want to bring all those different relationships, including the institutional ones and curators and these people, a little bit tighter into the web before it’s then a final completed project that will be a book.

If my work deals with the interwoven and increasingly porous and disappearing boundaries between public and private realms, this is my response to that in my own life in some ways. And to what degree do I perform within this? And what degree do I want to be, for lack of a better phrase, alone? How much can I keep it up? How much can I perform? How much do I need to retreat? But all of it is in the recipe of what’s going on here.

Robert Sandler is an artist based in New York City. He makes work about humor, theater, and pleasure. He is currently represented by Kai Matsumiya Fine Arts Gallery.