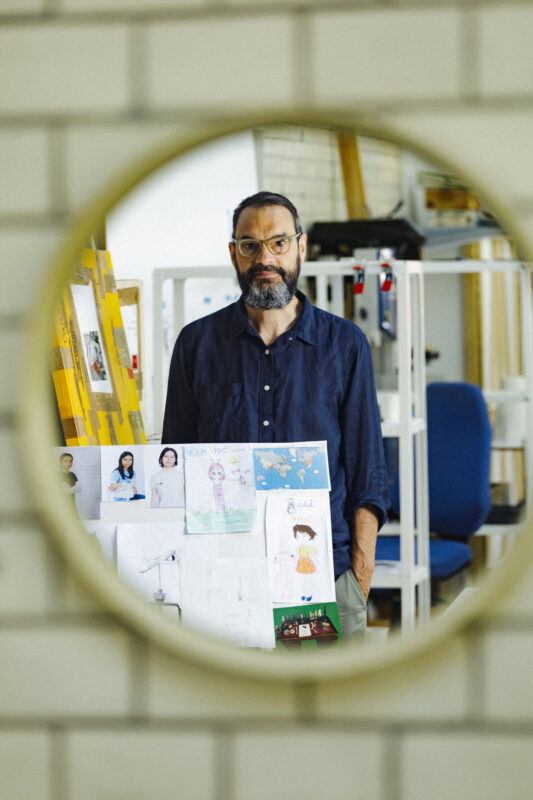

In the Studio

Sam Durant deals with traumatic histories while working to reduce harm

Jurrell Lewis – Your work engages with historical events, tactics of domestic control, and American imperialism. There are ways that you could approach these subjects outside of artistic practice, yet the pathway you’ve chosen to address or activate these ideas is art. What makes this the avenue through which these ideas feel best expressed or handled?

Sam Durant – This is a question I’ve been thinking about for a long time. Art is important in the struggle for a better world, because it gives us the dimension of feeling, of emotion, of pleasure, also pain, all of these things. What are we hoping for? Is it a different way of living with each other that’s more fair, that’s more just, that has less violence and subjugation? Well, we need art for that, all different kinds of art, because art is about becoming more fully human, reducing inhumanity. We need art for that. I think art is an important part of a struggle for a better world.

That said, I don’t think art is activism or doing politics. If you want to get change, political change, you’ve got to do politics, and politics is about power, it’s not symbolic. I believe that art and politics are separate worlds. I try to make a separation between the things I do politically, the struggles for things in the political realm, and what I do as an artist in the aesthetic realm, if that makes sense.

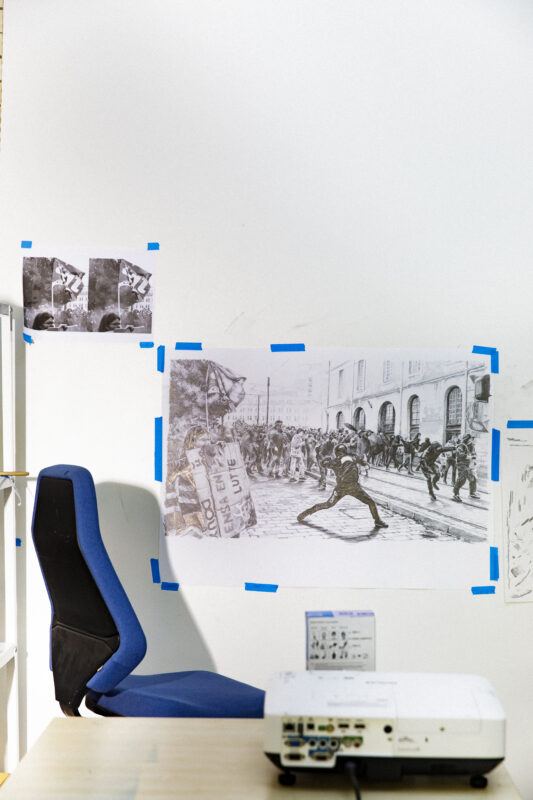

In Untitled (Drone) (2021), you installed a sculpture on the Highline that takes the form of an abstracted Predator drone and edited a zine about drone surveillance and warfare to accompany that public work. Could you talk about the different ways that sculpture produces or disseminates knowledge, both through a collection of research and interview-based information and a physical experience with the drone as an object?

You mention something really important, and that is the actual object, the presence of the object, this sculpture of a drone and how affecting that is. I do a lot of research, and yet all this information cannot be visible without the object, the sculpture. I developed a body of knowledge about drone warfare, the many innocent people killed, how many strikes are going wrong, how often it is terribly overseen and run, and the toll it takes not only on the innocent people that are killed, lives ruined, but also the soldiers that are flying these things–the incredible stress of that and the harm that it’s doing to everyone involved in the program. Many people know all these things, you can find out, but what struck me is most of society has no connection to that. It’s almost totally invisible in the United States.

That’s when I thought, “Oh, it would be amazing to just have this thing sitting there in the biggest city in America, in New York.” Of course, in some senses thinking about it symbolically to the rest of the world, New York represents the power and aggression of America, and so that seemed like the place where it would make the most sense to have this thing come back from everywhere else in the world. Let’s have it come back home and literally cast a shadow, a physical shadow. That was a way of making it real, and trying to make it really visible and physically present as a force, as an expression of American power and power in general. We see the war in Ukraine is increasingly being fought with unmanned drones, and this is clearly the future of warfare, unfortunately, this subject continues to be important.

Within the abstraction of the drone, there’s also what I interpret as a gesture of kindness or consideration in stripping it of the more overtly threatening accouterment, it’s cameras and weapons and such.

I mean, this is something that I really learned from Scaffold (2012). I had the sense that you can deal with these traumatic histories as long as you don’t represent suffering people. I thought that a symbol or an abstraction could not retraumatize, and I was wrong. In Minneapolis, that symbol of the Mankato gallows was recognizable. Untitled (Drone) was the first public work I did after Scaffold, so I tried to really learn from that. I realized that you can abstract much more and yet work to find a space of recognizability so there’s a provocation in the work, but hopefully without traumatizing people. Untitled (Drone) is meant to be in support of people who’ve been harmed by American power and I don’t want to harm them again, so that was a big part of thinking about it.

Often your work references historical trauma or evokes feelings of discomfort, referencing history and current events that are difficult or painful. How do you manage this confrontation, direct it or mitigate it, and avoid hostility while still making grievances or traumas present?

Each work, not only each work, but each context in which the work is seen requires a lot of care and really thinking through when you’re dealing with these confrontational things, these things that can be really traumatic for some people. I worked with Rick Lowe (artist and founder of Project Row Houses [1993-2018]) in New Orleans, for a number of years and I learned a lot from Rick. The main thing is, you have to talk to people, and you have to especially talk to the people that might disagree with you. That’s the most important thing you can do. Most people want to be seen and heard, and if you show them that respect and you show them that you care enough to listen and hear what they have to say even if they disagree with you, that goes a long way. And of course, you often get great input.

That’s what we did with The Meeting House (2016). I met with community leaders in the town of Concord, Massachusets, and some of them were really against this idea of looking at Concord’s racial past. They thought this was not a good idea, but I spent a lot of time talking to them, and in the end I said, “I respect and recognize that you don’t like this project, but I think it’s really important. I think it’s really important and we’re going to do it, and we’d like to have you be part of it, but we also understand if you don’t want to be.” That work beforehand allowed the project to be as good as it could be. That’s always the case. You need to talk to people, and that’s what didn’t happen with Scaffold. Unfortunately, we didn’t meet with Dakota community leaders, and I know for sure if we had done that, there would’ve been a very different outcome at the Walker Art Center.

Then of course, in that context then you always have people that you can’t meet, that you don’t know, that are coming to a work and maybe have some personal connection to the historical issue or the ongoing issue. I mean, with Untitled (Drone), what I imagine was a recent immigrant who has lost family members or who’d been traumatized in a drone strike, coming across Untitled (Drone) and being re-traumatized. We tried to meet with all of the aid groups that work with people coming from countries that have been affected and talk to them and see what they say, so we did all that work. Even so, you never know what’s going to happen, and that is the risk with this kind of art.

Have any of the conversations and collaborations that precede and go on during your works had a lasting impact on not just the project, but across your practice? That have made a lasting impact that changes how you approach a problem or project generally?

Certainly, I would say I learn things from every project that I do, especially if it’s either collaborative or in the public realm. With Scaffold it was really important in two ways, and the first one was when it was exhibited in documenta in 2012, I realized that it’s much easier for people to talk about other people’s history. U.S. history was very useful because it wasn’t German history, and so German and European people could use it as a way to talk about and think about their own history. That was really surprising and interesting to me, it made me realize that working with American historical issues in Europe works because people understand it, and in some ways, it’s more productive for generating discourse. Then of course, when the Scaffold came to Minneapolis, it was not about somebody else’s history, it was about this one particular thing. It became about this very local history, and that happened at a particular time and historical moment, and what happened, happened. So that really influenced me, particularly with thinking about Untitled (Drone) and how to work with symbols that could be potentially really hard for people and how to try and minimize harm while still opening up the subject matter for discourse.