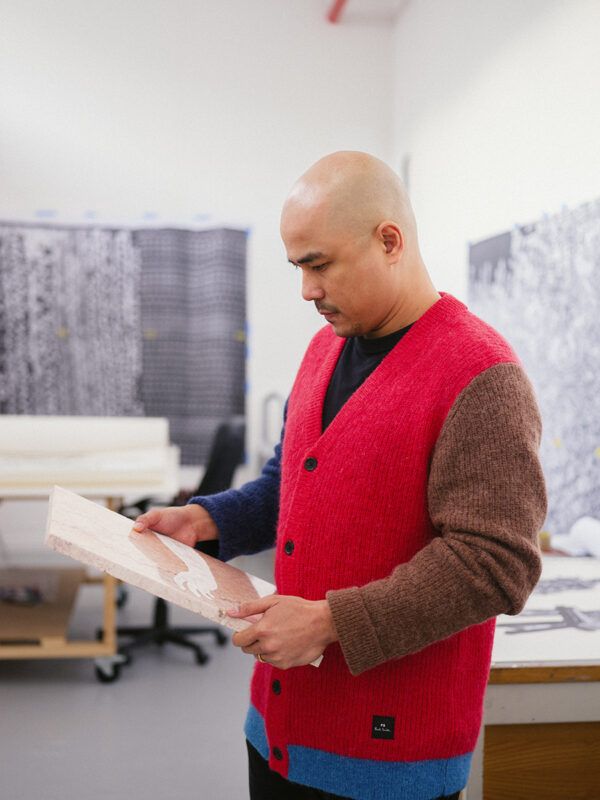

H. Daly Arnett—Can you speak a little bit about the process of receiving the invitation and what you felt like the expectations were for the Ashmolean Now series?

Pio Abad—I was invited in 2021, just after the UK was coming off its third lockdown. Lena Fritsch, their Curator for Contemporary Art, invited me into a space called “Gallery 8,” which used to contain the cabinet of curiosities that served as the foundation of the Ashmolean Collection. Through a series of refurbishments, this cabinet of curiosities—which is the Founding Collection—was moved to a much larger gallery adjacent to its prior location. Gallery 8 then became a project space for the museum. When Lena invited me to think of doing a show in conversation with the collection of the museum, it became clear to me during the first site visit that it was going to be a conversation with the whole idea of cabinets of curiosities, which obviously is intertwined with the age of discovery, which ultimately is intertwined with the age of extraction, which then goes back to nation, goes back to empire.

While the initial scope was just to engage with the Ashmolean Collection, I was able to expand into other sites throughout Oxford because I wanted to delve into the complexities of Oxford as one of the oldest sites of knowledge in the world–a place that has necessarily shaped how we understand categories and taxonomies.

My approach to the exhibition quickly became less like a treasure hunt and more like a process of connecting dots. Sometimes those dots existed outside Oxford, and other times they were really, really local. One of the first objects that I came across that became a starting point of the entire project was an etching from 1692 that was at St. John’s College. The etching is referred to as the “Portrait of Prince Giolo,” but it’s actually an advertisement for the exhibition of a Filipino man described as ‘The Painted Prince’ who was taken by a British pirate from the south of the Philippines and displayed (initially in London) as a curiosity because he was covered from neck to toe in tribal tattoos.

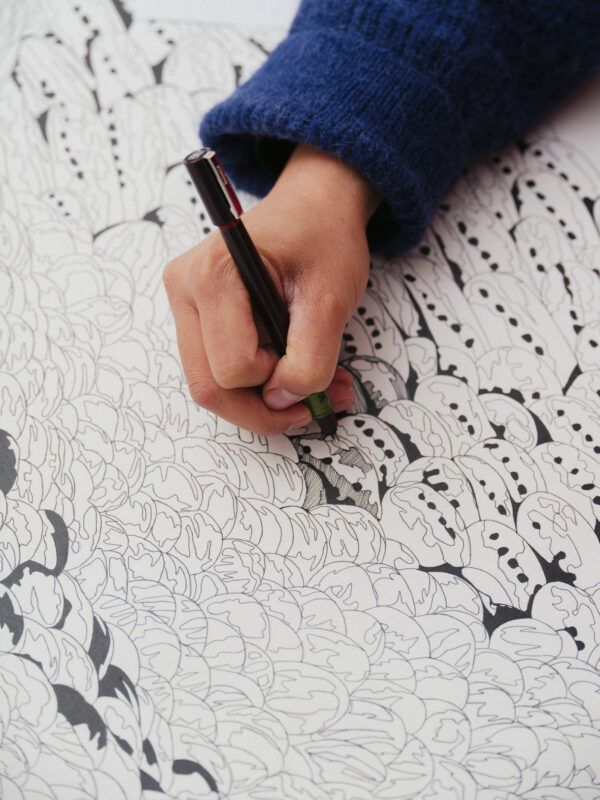

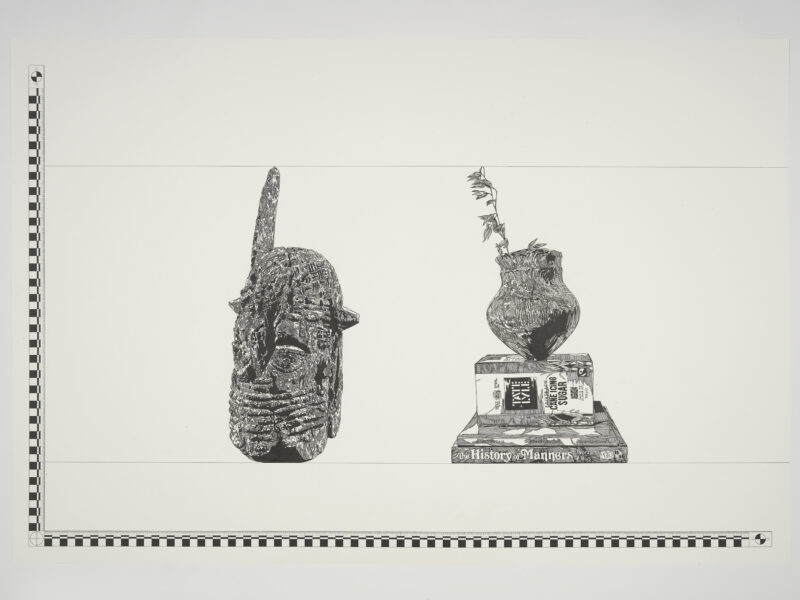

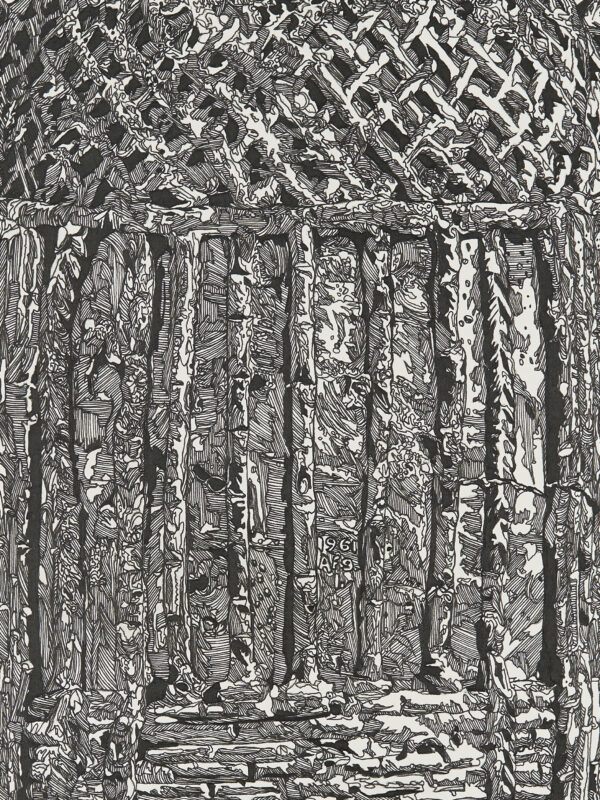

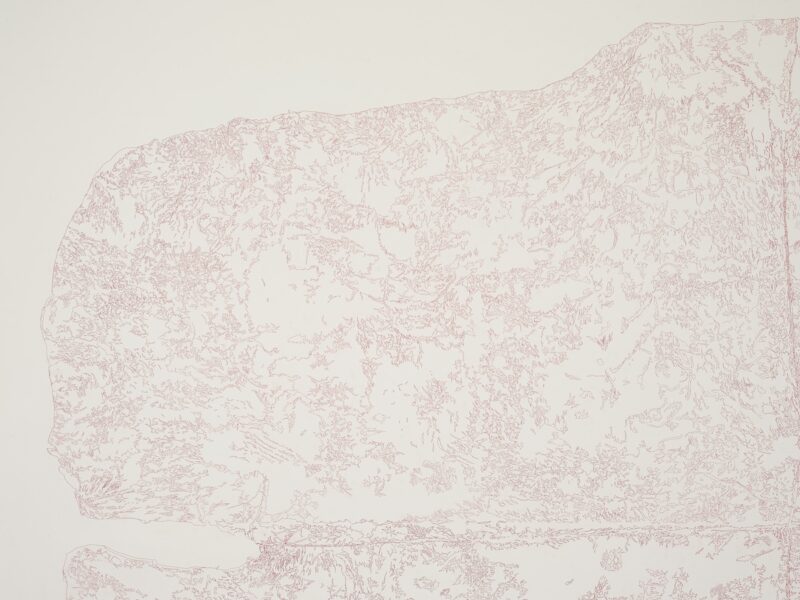

Often the objects I end up translating into intricate drawing are objects that have been excised from official accounts or are in archives but don’t really have any kind of prevailing taxonomy. Describing them is really an act of asserting their presence, presenting them not as objects but as maps. So that element of mapping has always been present.

HDA—Where does drawing fit in—or begin—in navigating these exchanges?

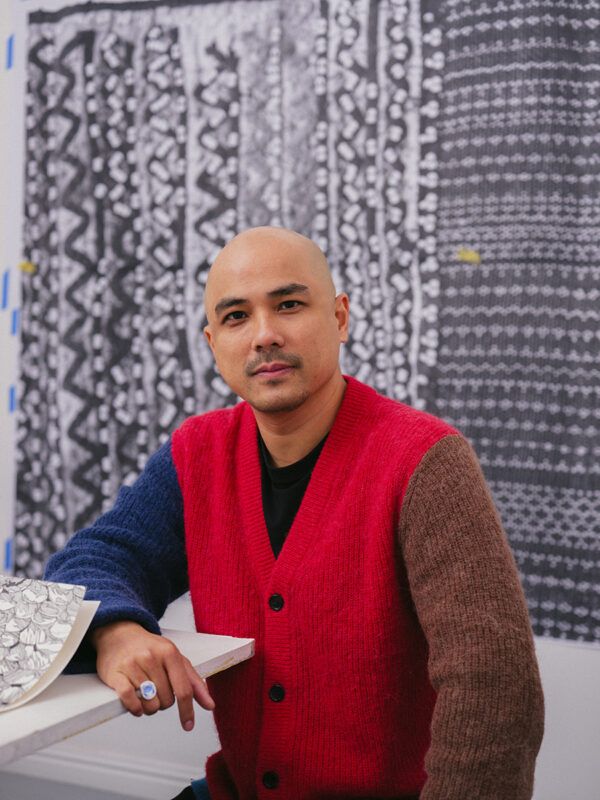

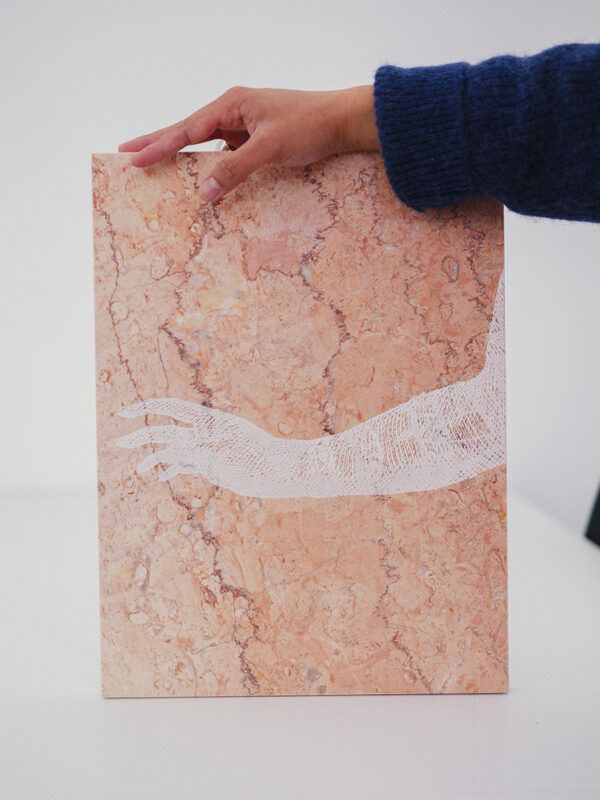

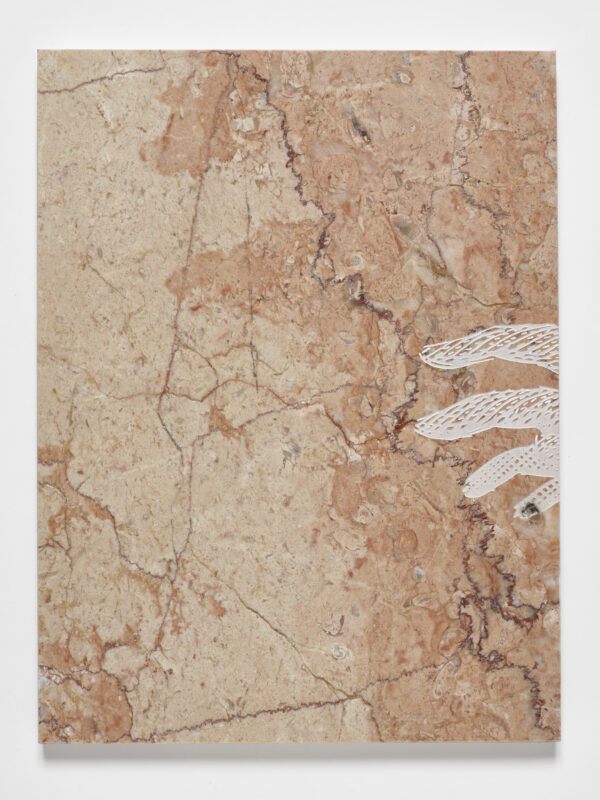

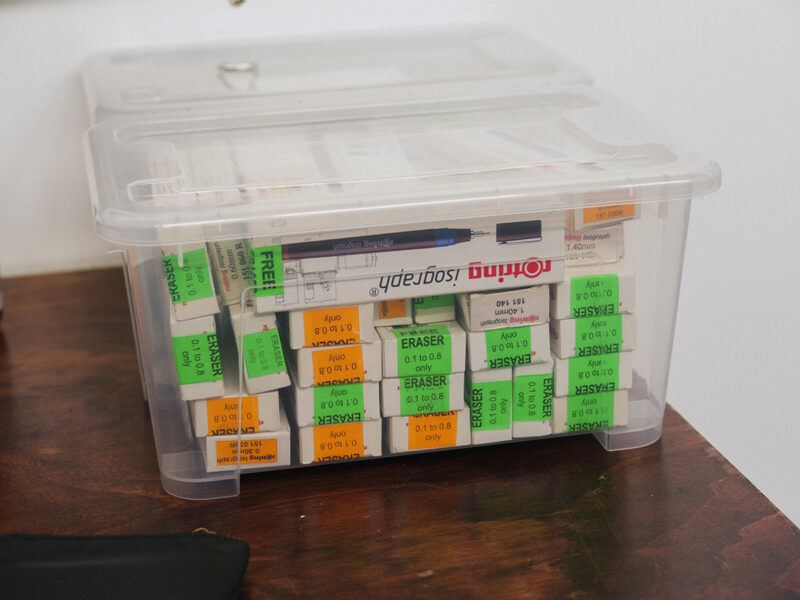

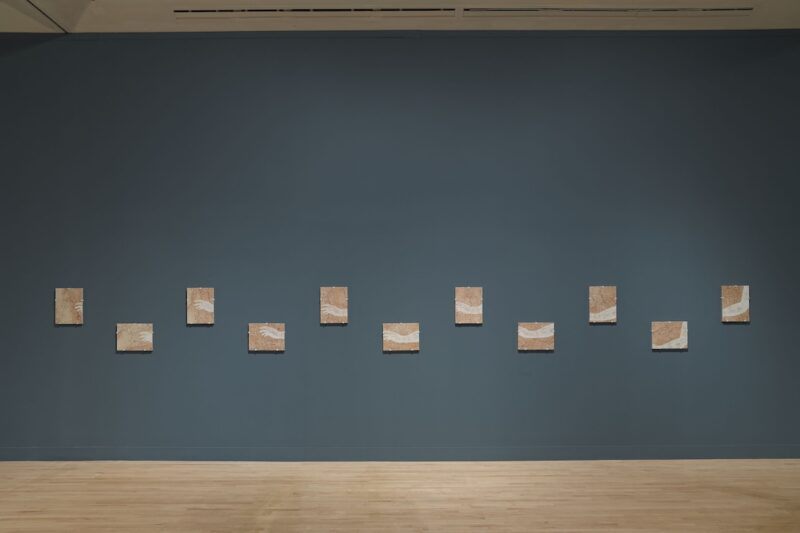

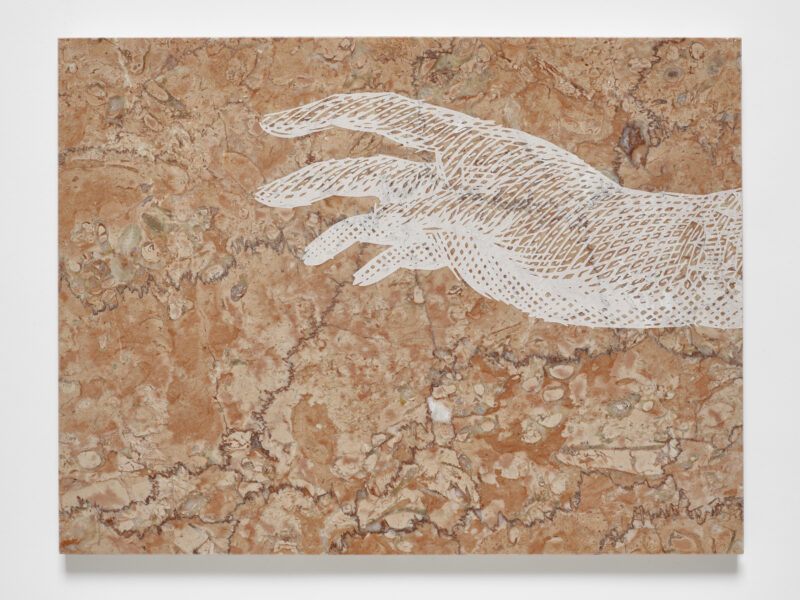

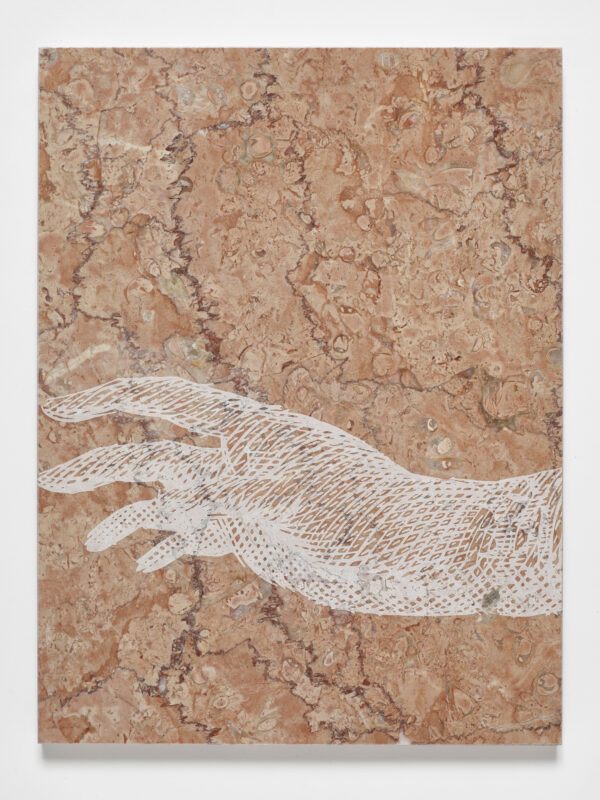

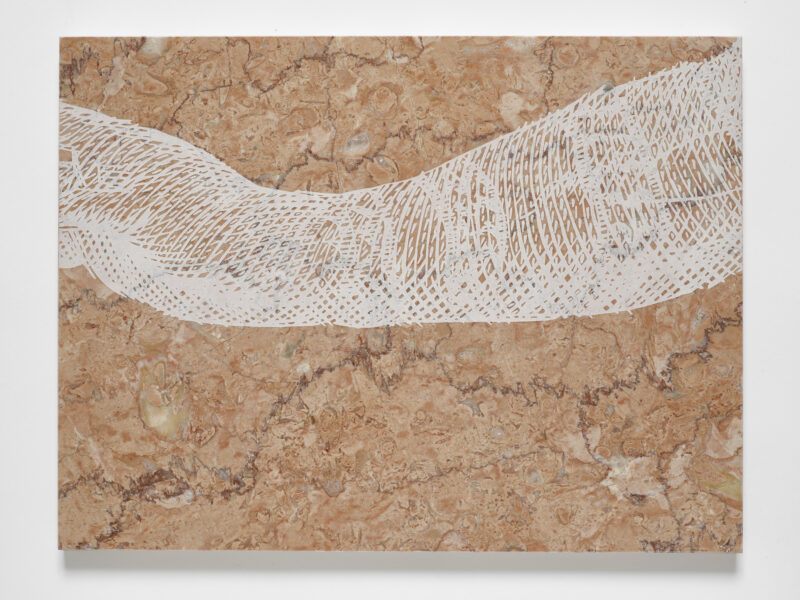

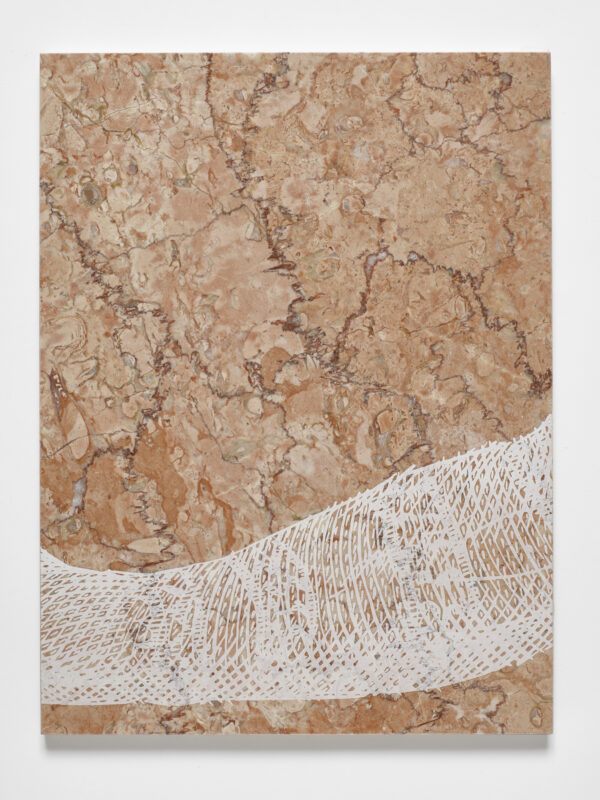

PA—Drawing is probably the beginning of everything I do. It’s very much a process of mapping, particularly with how I draw. In the case of Giolo’s Lament, the work, the process involves tracing an existing drawing, the ‘Painted Prince,’ and then transferring it to another material, where that beautiful hand of the so-called ‘Painted Prince’ ends up becoming this monumental installation spanning eleven slabs of marble. In the other drawings in the show and throughout my practice, where I am not tracing and transferring, there’s an element of plotting coordinates. As you connect these coordinates, you conjure up an object. But for me, they’re less objects, but more like a series of location points.

HDA—I’m interested to hear you describe your drawing practice as a type of mapping.

It seems relevant, here, that your family’s ancestral home in Batanes is on the Northern end of the Philippine archipelago. Mapping a nation across an archipelago, cartographers may understand waterways as either points of connection or separation, with Batanes marked as potentially isolated. This work came from a moment of isolation in your life, with the lockdowns during the pandemic. Between sites of connection and isolation—especially as overdetermined by mapping—I am wondering about the memoirist texture of the Ashmolean exhibition.

PA—Batanes has been such an important site not just for me as an artist but as a human. But it has not really figured in my work for a long time. It suddenly asserted itself as a nucleus of so much of this thinking around mapping around the instability of borders, around the kind of permeability of family history, geological time, and the instability of political narratives. With Giolo’s Lament, in particular, how Batanes asserted itself into my research took me by surprise: I was at St. John’s College looking at this etching from 1692, but Giolo himself, the ‘Painted Prince,’ is actually from Mindanao, which is the southernmost area of the Philippines. Looking deeper into that history, I found out that Giolo was taken to London by a British pirate named William Dampier, who was the first Western person to land at Batanes. I ended up looking through his diaries of that journey, and he talked about the rice wine that was consumed—which is still consumed now—and talked about these areas of Batanes that actually have remained the same since that point. It was funny to begin the research in Oxford and end up at home.

As I was going through the story of the ‘Painted Prince,’ I found he was kidnapped with his mother, who died at sea while on their journey to the UK. There was a really beautiful and sad passage in Dampier’s journal that describes Giolo’s grief while looking at the sea, wanting to cast himself into the ocean. My mother is buried in Batanes, so I encountered an intermingling of my grief and Giolo’s grief in a serendipitous way as this etching that I discovered in Oxford ended up being about home. Giolo’s Lament came from a need to turn this story into something more monumental, to rescue this individual from the archives and talk about him not in terms of being a curiosity (which is something that I would never be able to identify with) but to cast him as a grieving son (which is certainly something that I would identify with). So this intermingling of personal and research-based narratives came together, I think, quite beautifully in that piece.

HDA—Quite beautifully. What a wonderful opportunity from such a distance to find a connection to home.

PA—I realized that so much of the work over the past few years has been shaped by this grief that in a way, you never really, it’s not something that’s ever resolved, it’s just something that exists. I like this. Maybe it’s a bit cheesy, but I read somewhere that grief is like, it’s a hole in the middle of you that you never fill but the best you can do is embroider around it. You can elaborate that grief in different ways, and that becomes a way of just navigating it constantly.

It doesn’t seal anything up. You kind of just over elaborate on this chasm, really. Or you decorate the chasm. My mother passed away in October 2017, so in so much of the work that I’ve been making I’m finding different ways to articulate that grief—whether it’s a bracelet reimagined as a giant effigy or in this hand (in Giolo’s Lament) that may be grasping someone or fading away.

HDA—This presence of grief and love seems to inform some of the ways that you have to bristle against narrow definitions of your work as either institutional critique or conceptual art. How do you engage, or not, with those labels?

PA—I definitely begin [some projects] with a conversation with a museum as an institution; with the museum as a site where for better or for worse knowledge is produced. I’ve been grappling more recently, and this may have begun with three most recent projects that are situated within different museological contexts—Carnegie International, The Taipei Biennial, and the Ashmolean. There are exhibitions in an artist’s life that really reorient them and, for me, taking part in the Carnegie International in 2022 was a real transformation in terms of working out how conversing with the teleological structure of the museum can lead to a place of tenderness. The way the curator, Sohrab Mohebbi, interwove the geopolitical from a place of intimacy was exciting to be part of. Working on these exhibitions made me rethink what I’m doing with my time with all of these drawings, that there has to be more than just a forensic reconstruction. I wanted to find the space for tenderness… to construct a visual language in a way that it’s more personal than I was initially ready to admit.

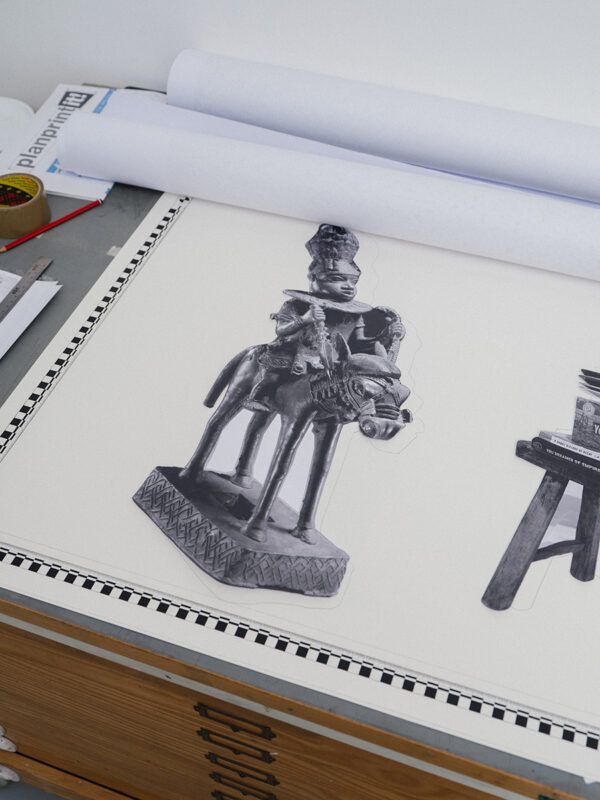

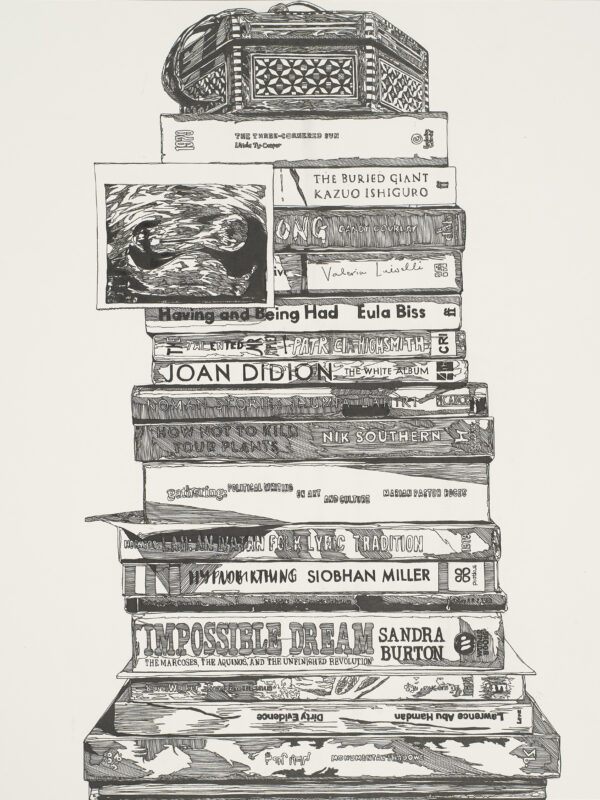

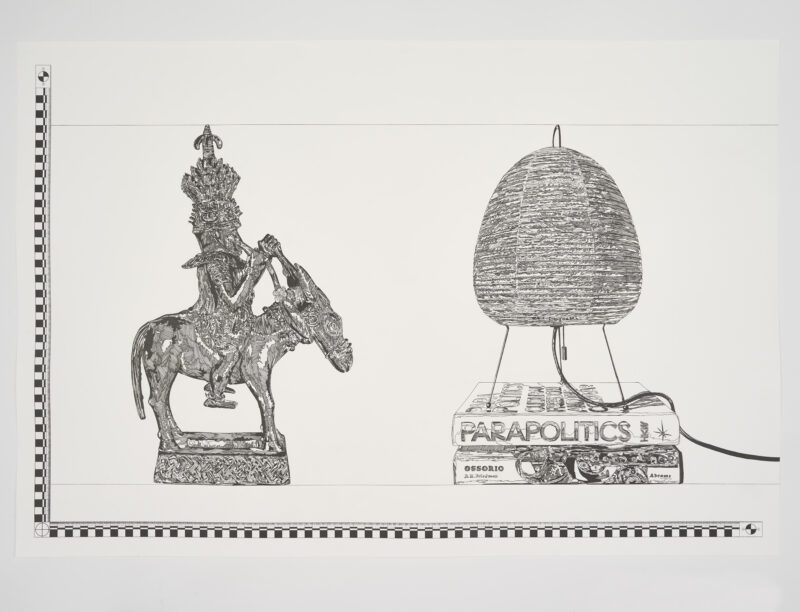

HDA—A way that this arrives for me, at least, in the recent set of 1897.76.36.18.6 ink drawings is through your meticulous use of scale. You’ve assembled in the drawings stacks of objects from around your apartment to match the height of the Benin bronzes. Where did the choice to use height as the scalar frame come from?

PA—When I think of scale, I think of height. Maybe it’s because I’m not very tall [laughs] but I wanted to measure these objects to honor their original context (as votive objects, as artifacts, as archival documents) rather than as a symbol in service of an argument. I always insist on going back to the intimacy of artifacts, because that’s how we really understand objects in relation to our own scale. So this idea of measuring things by height, interestingly enough, actually came from a need to measure things not in an empirical way, but through emotional or personal means. I mean, it’s funny because it’s still an act of measuring the object, but in creating an equivalence between, say, the ivory mask of the Queen mother and a portrait of my mom over a couscous pot creates an apparent fragility—the stack of objects next to the solid artifact is very much a temporary composition.

It goes back to your question about my ambivalence towards these labels of institutional critique, or these set categories that the art world has placed on art. Sometimes people confuse the world created by an artist, which is a world replete with possibilities, with the world that is out there—that activists, politicians, and legislators exist in. The imaginative possibilities of being seduced by an ink drawing is where I want the work to live.

HDA—In the way that you’re speaking about seduction and the imaginative possibilities of a drawing, there is an optimism perhaps informed by the political teachings and activism of your parents from your time growing up in Manila.

PA—I always say that my parents will always have a much broader imagination than I can ever aspire to have, because they raised the four of us while going through this kind of unenviable–also really thankless—task of restoring democracy after twenty years of authoritarianism. It sounds grand because it is grand!

Knowing what they went through in their lives and situating my studio practice against that canvas always reminds me of the scale of what I do, which is not that grand at all. This is both really empowering and clarifying. As much as the work is invested in political histories or talks about histories of activism, I’m still drawing. It’s empowering and humbling at the same time to kind of understand the scale of what they went through compared to what I’m trying to work out in the studio.

Having been a witness to my parents’ political struggle has given me a really, really solid understanding of the possibilities and the limitations of art. I take that with me with everything I do, that there is an attempt to cover these monumental moments in history, but at the same time, it’s still very much a drawing. And I need to spend as much time thinking about how beautiful that drawing is. And I think that’s why beauty is always this insistent element in my work, because as much as I believe that art has this transformative potential, it will not realize that potential if people don’t want to look at it. And so the power of seduction for me, really is the power of art.