Essence Harden – How does Los Angeles, itself, offer a particular range of questions that you’re asking of your work?

Nikita Gale – Something about Los Angeles is that there’s so much concrete. I can’t remember what the percentage is but it’s a staggering amount. There’s an unbelievable amount of the city that’s paved in concrete and that has made its way into the work in a really direct way. I work with concrete a lot because it’s a material that I associate with this quality of ambience.

There’s something really inherently nefarious about it because it connects to this impulse to control or flatten nature or to continue to increase the mythology of the divide between humans and the natural or what is natural or biological. Concrete is this material of authority and power, so when you see a thing that’s paved, there’s obviously some kind of agenda of power associated with it. Whether that’s the Department of Transportation or a property owner wanting to manage the land around their property.

Could you speak about the way you use certain materials as portals, dislocating viewers, removing them from a sense of assuredness, and redirecting their associations or understandings?

I love the idea of a portal because that’s something I’ve been thinking about much more specifically in terms of the way that I use the language to describe what my work is doing. What I want it to be doing in space, what kind of scenario it’s creating for someone who’s experiencing the work. It’s about the embodied experience of the work. It’s almost like I think of each of my works and each installation as a portal or an invitation to a conversation.

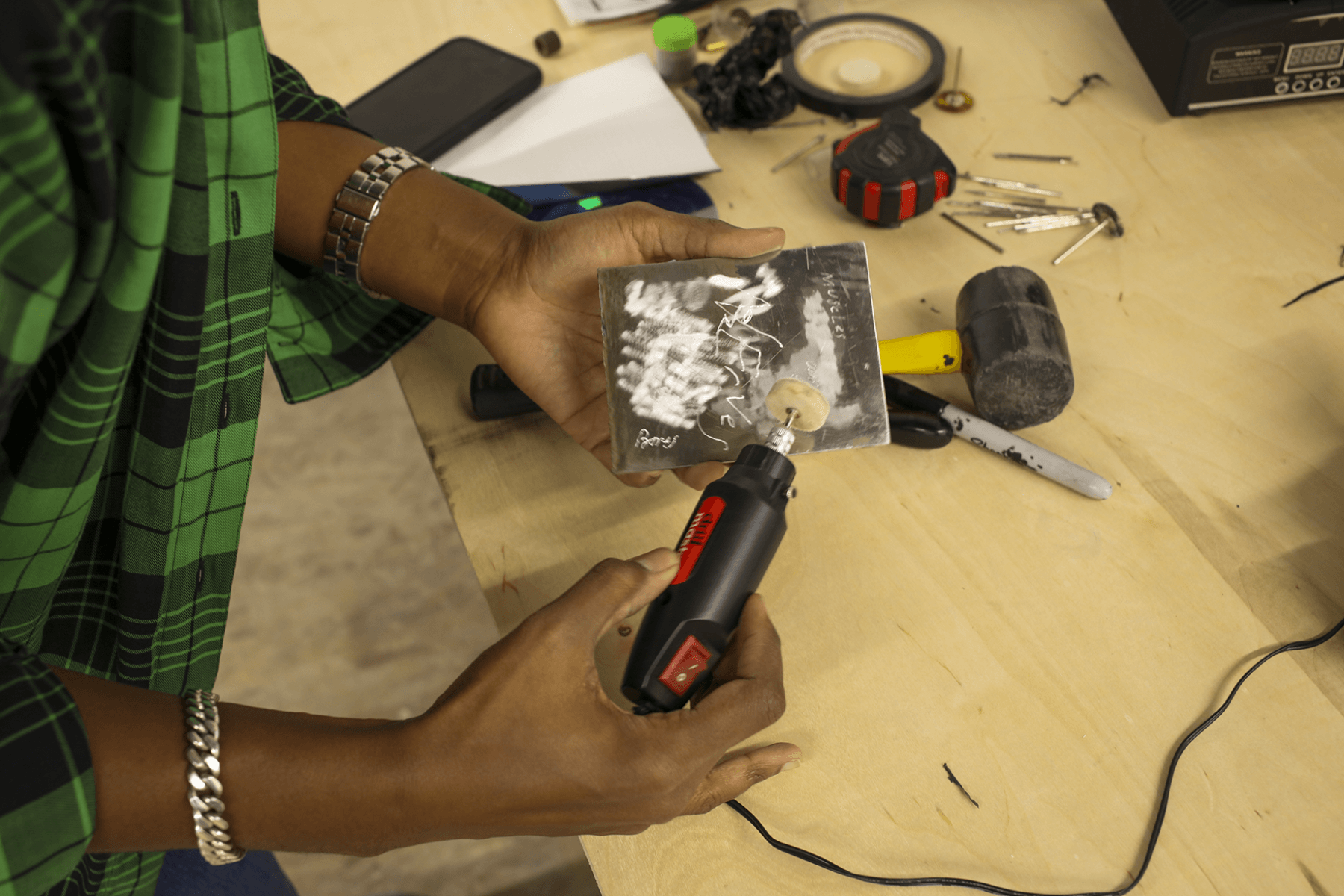

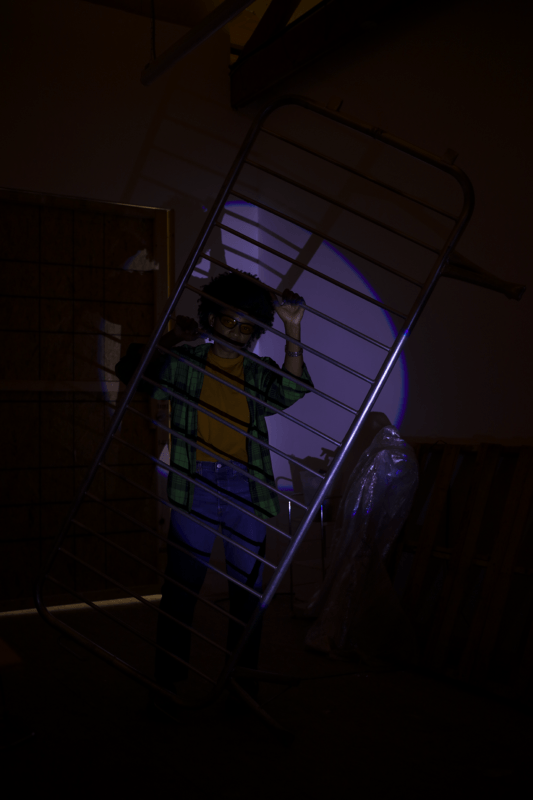

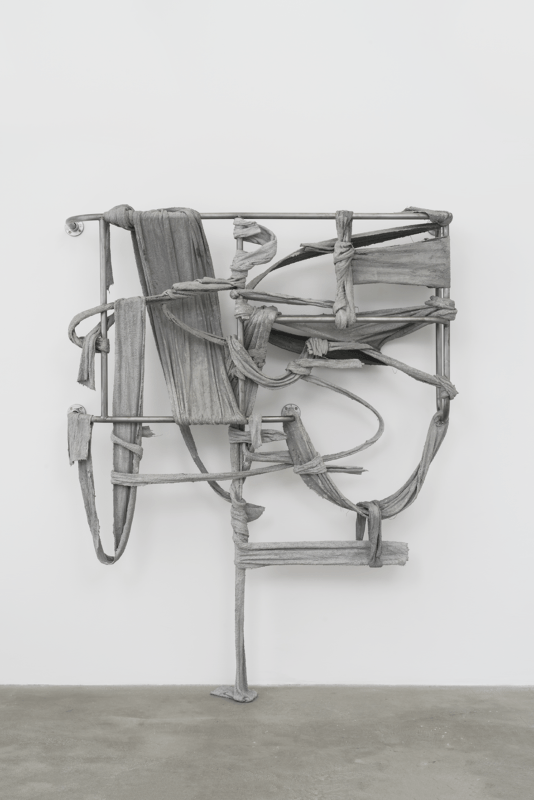

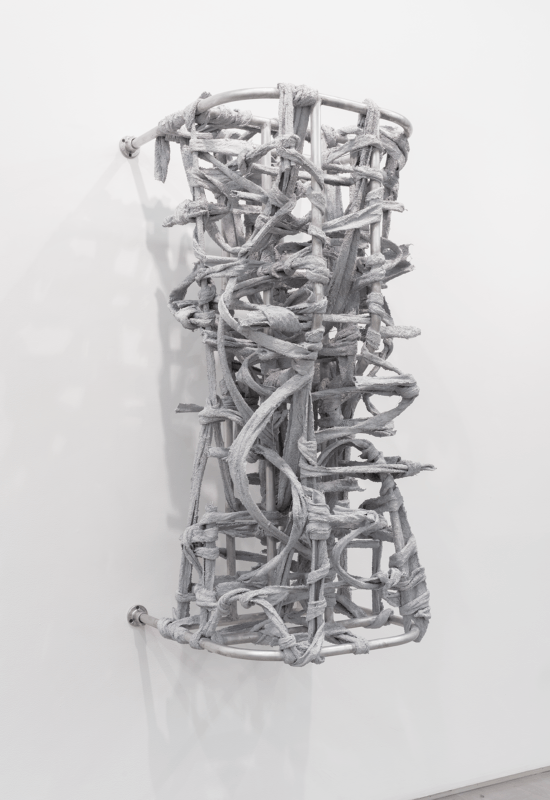

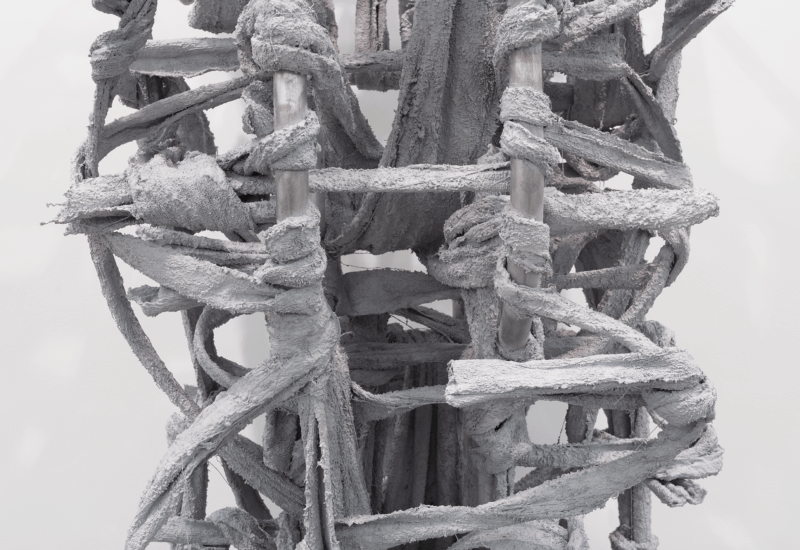

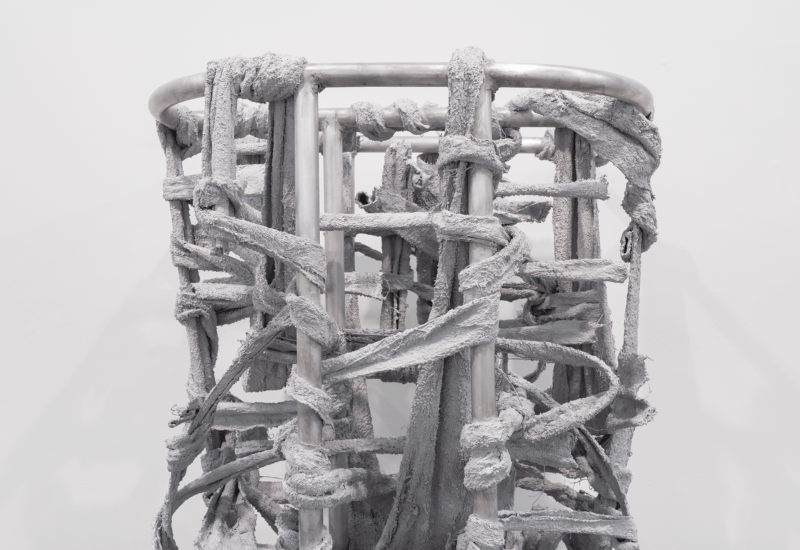

The RUINER pieces, for example, are these aluminum armatures that gesture toward objects or designs like crowd control mechanisms or banisters, that you might associate with public institutional structures that are meant to kind of guide movement through space, suggestions for a certain type of performance to take place. I combine those materials with concrete-hydrated, terry cloth strips. I have always loved this idea of a material that’s meant to absorb, and clean the body, and has a really intimate relationship to touch of the body. The concrete’s crucial, because it’s doing the thing that it does in the context of public space, right? It’s delineating and hardening and it’s recording the intentions or the agenda of whatever authority is controlling the space.

Those works are creating a permanent record of a gestural, almost fugitive movement between structures or armatures associated with control. The concrete creates the recording of these gestures that are not meant to be recorded, or often are not recorded because they’re sort of the moves that you make to get in between or work around the structure. The result of that is that it ultimately makes that original armature or infrastructure useless, which is why I call them RUINERS, because it’s this idea of ruining whatever that initial armature structure represented and creating something new.

How does technology, as a kind of decision-making and a mode of planning people’s lives, operate as a specter within your work?

Concrete is a technology that’s been used for a very long time to control and maintain. Think about the way that concrete has fundamentally shifted a relationship that humans have to time and speed, or think about something like the Interstate system of the U.S. and how that connects to a history of extremely violent, colonial impulses.

One of the primary arguments that has emerged around climate change discourse is just this general anxiety about water; there not being enough of it or there being too much of it, and the narrow range of tolerance that human beings have for the amount of water that is too much or too little. It’s fascinating to me because, understandably, it’s so human-centered. Something that I’ve been thinking more about in terms of how I can make work or develop these conversations around the work, is the idea of creating structures or making proposals for how do we prepare the planet for the post-human phase.

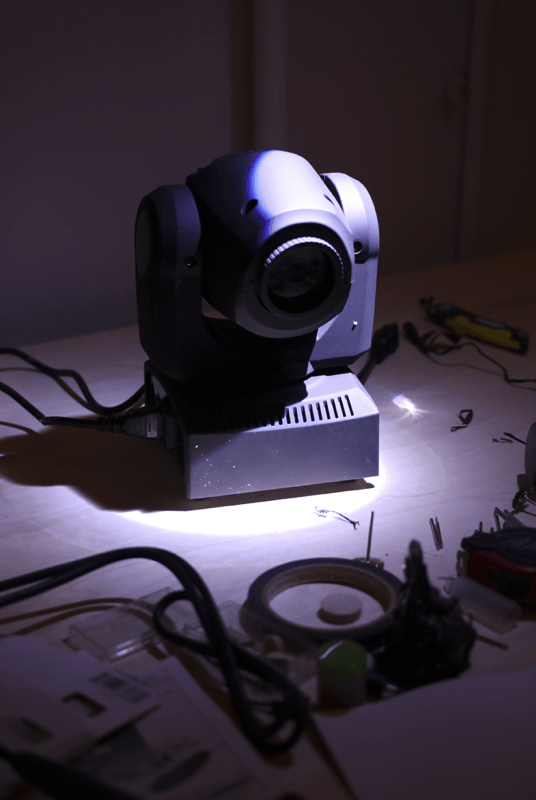

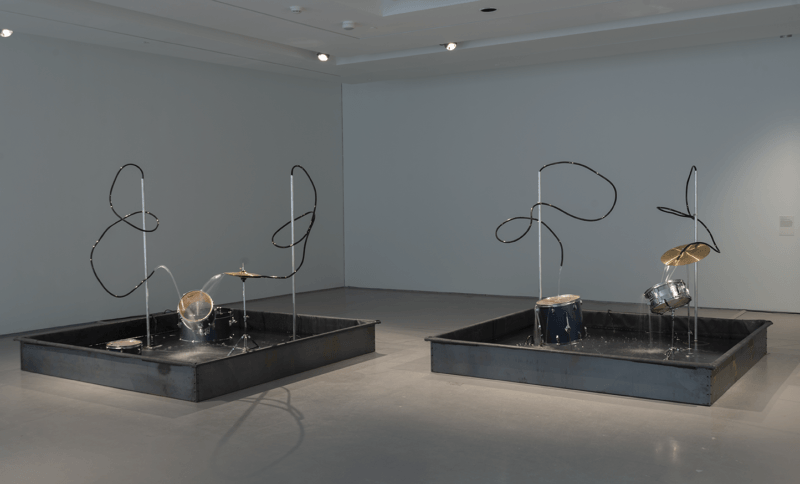

When I made DRRRUMMERRRRRR, the whole premise was to create the scenario where there’s a technology or tool, in this case a drum set, that’s meant to be manipulated or activated by a single human body but that is spread just far enough out that it would be impossible to activate it as one person. But water, the element there’s so much anxiety around, has the ability to animate all of the fountain simultaneously. It’s thinking about the possibility of all of the cool, interesting things that might happen to these tools when there are no more humans left to engage with them.