New Red Order is a public secret society whose core contributors include Adam Khalil, Zack Khalil, and Jackson Polys. Interview conducted for Art21 in July of 2025 by Jurrell Lewis. Original photography for Art21 by Mel Taing. All other photography courtesy of New Red Order.

In the Studio

New Red Order envisions a new world

Jurrell Lewis—A good starting place for the conversation might just be to ask you what exactly is New Red Order?

Zack Khalil—New Red Order is a public secret society dedicated to expanding Indigenous agency and the rematriation of all Indigenous land and life. New Red Order emerges in contradistinction to the Improved Order of Red Men (an actual secret society, akin to the Freemasons), which has been active in America for centuries now. They trace their lineage back to the Sons of Liberty, an organization famous for the Boston Tea Party, a foundational act of the American nation where colonists dressed up as Haudenosaunee and dumped tea into the Boston Harbor.

The Improved Order of the Red Men is a secret society that still exists today. At their meetings, members “play Indian” and dress in faux native regalia. Many U.S. presidents were members, most recently Franklin D. Roosevelt. This secret society represents the desire for indigeneity, which exists at the heart of America’s myths, dreams, and political foundations. Of course, this desire for indigeneity from non-Indigenous or non-Native people can often have negative consequences in terms of appropriation and cultural erasure. At the same time, if this desire is so deeply embedded in the Americas that it can’t be avoided, how can it be re-channeled to not negatively impact and extract from Indigenous people, but actually encourage reciprocal relations?

In our current period of existential and environmental catastrophe, desires for Indigenous worldviews and epistemologies signal an awareness that we’re entering, or are in the midst of an apocalypse. There have been many apocalypses, of course. The Ancient Greek root “apokalips” means an unveiling, so it’s not about the end of something but about revealing and changing. As we face this existential environmental catastrophe of climate change and so many other things, people look towards Native people for knowledge on how to get through this time because: A. we’ve already survived an apocalypse of sorts and B. because they’re looking at our ways of living and coexistence with the natural world as knowledge that was previously disregarded as unhelpful and primitive, but is now being seen as something that we all might need to save ourselves.

Adam Khalil—As a reminder, anyone and everyone can join New Red Order by calling in toll-free at 1-888-NEW-RED1, or signing up at NewRedOrder.org.

The three of us are core contributors to New Red Order, which exists beyond the three of us. We resist the framing of an art collective and the temptation to be subsumed by the art world because, as a public secret society, New Red Order could be a political think tank, a religious cult, or some other kind of collective formation.

I was recruited into New Red Order in 2017, when I met Jackson Polys, who told me about this shadowy, public secret society that offered ways of channeling the desire for indigeneity toward Indigenous ends. One facet of that thinking is about the position of “the Informant.”

Jackson Polys—Informancy includes dynamics occurring when individuals and institutions reach out to Native people to try to learn about Indigenous epistemologies in order to find what the continuance of those practices might enable in terms of discovering a different kind of relationality or futurity.

It’s been important for us to use those moments as activations (both welcomings and warnings )to interrupt a pursuit of this knowledge without a closer examination of one’s own positionality and intentions. We try to use any opportunity, including looking to art and artists, to instantiate a reconfiguring of one’s own relationship with Native and Indigenous people on a foundational level.

AK—We can accept and be complicit in our own informancy, understanding that it’s an extractive relationship between us as contemporary Indigenous artists and the broader art world. In that acceptance, we can foreground our practices and projects to create reciprocal dynamics rather than extractive ones, asking people to join us and inform on their desires for indigeneity. That way, that desire can stop being an obstruction and become a pathway to futures that we all hope to inhabit.

JP—We’re interested in art that does something, even while the conflating of art and utility through Native art appreciation continues to push Native art into the past and bracket it as not really contemporary. We’re interested in possibilities of recombining utility and art to upend expectations and act as a destabilizing force, so we might all find ways to engage with each other differently.

JL—Rather than reject the dynamics of informancy, you find agency within that position, which seems to manifest in the ways your work educates and challenges simultaneously. Could you talk more about how finding agency in informancy shapes your work?

ZK—Our role as informants for me feels like a position of agency, because it often functions as a bait and switch. We’re asking other people to inform, and we’re owning that position of informing on our own communities and cultures as Native artists. But generally, we don’t provide much information on our communities, cultures, and, specifically, traditional practices.

Dexter and Sinister (2023) is a good example. A small part of the dialogue between an animatronic tree and beaver in the work is rooted in traditional Anishinaabe understandings of the role of beavers in ecosystems. Where settler colonial society thinks of them as industrious, destructive, and human-like, because they change the world by cutting down trees, from an Anishinaabe perspective, they’re seen as world builders who create new ecosystems and are emblematic of wisdom, the practice of using knowledge with care.

There’s that little kernel of traditional Anishinaabe awareness of what a beaver is from our view, but the real thrust of the work is a deconstruction of the notion of private property and its relationship to Hobbes and Rousseau: a critique of their overly simplistic understanding of ‘the state of nature’, whether that’s an Edenic egalitarian state or the war of all against all. What we’re really informing on most is settler colonial culture.

AK—This idea challenges the concept of informancy itself, to present settler culture back to settlers instead of presenting Indigenous culture to settlers.

JP—We recognize the ongoing dynamics of informancy and hope to utilize those conditions to create material change. That has extended to our Give it Back project, where we’re looking at instances in which people voluntarily give land back to Native people. We’re trying to promote that practice while finding ways for people to peek into the potentially sticky dynamics of those instances.

Our examination of figures like Thomas Morton is a continuum of that practice, where we’re finding this figure that represents the complication of possibilities or options when advocating for Indigenous people. At the same time, Morton was perhaps overstepping, embracing freedom too much. Yet Morton as a figure allows us to examine a prism through which we might find possibilities that allow us to reach a different kind of future.

JL—Give it Back exists both as a reality and an artwork. It’s something that you’re facilitating and observing in the world, but also something you reproduce as an artwork in the form of real estate ads that represent these real instances of land being returned to Native people.

ZK—The Give it Back project is about creating the conditions of possibility for the return of all Indigenous land and life.

A big part of the project is encouraging people to be agents of the future instead of victims of history and to think about how we all have a role in both constructing our contemporary reality and moving into the future. Give It Back promotes the practice of returning land to Indigenous people and shows all the people who’ve already done it. Since Standing Rock, the number of non-Native people who’ve given land back to Native tribes or nonprofits has been increasing at an exponential rate.

So much of that work is telling others that they have agency and showing that this process is not only possible, but already happening. The examples in these ads are real, but people can’t even comprehend that, because we’ve been conditioned to think that nothing can be done about it.

Give it Back is an encouragement to engage in this process and, more than anything, to discuss what that means. Not just to discuss what it means to live on stolen land, but what would it mean to give it back? What would it mean to be here together? For me, it’s not about kicking everyone out of America: it’s about creating new forms of kinship and reciprocity centered on the land and its original inhabitants. How can we call others into that process, and understand that it’s something that’s already unfolding?

AK—When we posted the real estate ads during our show at Artists Space, there were complaints from people saying, “I’m looking for an apartment. Is this a joke, or is this real?”

That was a failure and a success of that work, the return of land wasn’t a believable reality, even though it is actually a reality.

That was a maddening realization, where we were like, “It is real.” We realized we need to normalize this behavior, promote it as a lifestyle, and insidiously feed it back into the vernacular of corporate advertising, wellness, and all of these things that atomize us as individuals rather than collective orientations.

JP—The use of real estate ads allows for questioning of where notions of property might or might not inherently depart from Native epistemologies. If it took centuries to dispossess Native people of their land, what would it take for that land to be given back or to develop new forms of ownership?

That requires, in a transitory and practical way, identifying things that can be owned and transferred so we can create new forms of ownership or relationality later in time.

AK—There’s an interesting parallel in terms of the return of Ancestors or human remains to Native peoples: they need to be deemed as property in order to be given back to the communities that can reclaim them and rebury them as human beings. There is a necessary evil of passing through property to arrive at a more humane reality that should have been in place all along.

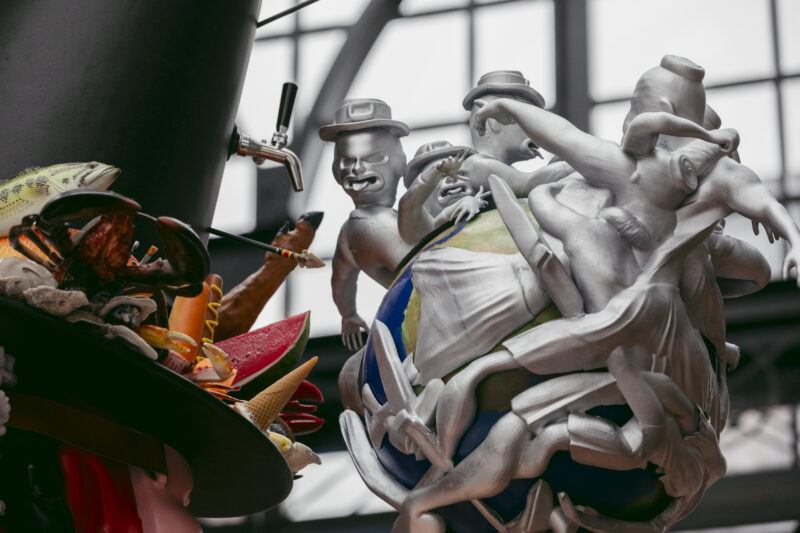

JL—You also mentioned Thomas Morton, and you currently have a new public work dedicated to him as part of the Boston Public Art Triennial. Could you describe what Material Monument to Thomas Morton is, and what the story behind it is?

AK—Thomas Morton is a historical figure who exists on the margins of American history and literature. He was demonized for a long time and then later valorized.

In the early 1600s, he came to the Americas as a merchant, not to flee religious persecution but to make money. Shortly after arriving, he got really fed up with the Puritans and decided to found an anti-colony a couple of miles away in present day Quincy, MA, which he called Mare-Mount.

At Mare-Mount, there was a crew of indentured servants whom he liberated collectively, so that they could start this kind of Dionysian free trade zone. He erected an 80-foot maypole and started hosting parties with the Wampanoag and Massachusetts, promoting trade of alcohol, weapons, and other things with those tribes. That was a big no-no from the Puritans and Pilgrims and ultimately led to the Puritans and Pilgrims arriving at one of the parties, killing everyone, burning down Morton’s home, arresting him, and shipping him back to England.

When he was in England, he wrote the first banned book in America, The New English Canaan. It was a screed attacking the Puritans’ and Pilgrims’ culture as repressive and based on subjugation and domination. It was also a love letter to Indigenous forms of sovereignty that he witnessed with the Wampanoag and Massachusetts.

Morton is a vapor or fog within the history of American culture and foundation, so he was interesting because he also presents another path. What could have happened if we went down this kind of neoliberal, capitalist Morton trajectory, as opposed to a Puritanical religious zealot trajectory of subjugation and domination?

ZK—In Boston, tourists come to learn about the colonial history of America, to soak up the Thanksgiving myth, and other mythological foundations of the Americas. Thomas Morton is a footnote to that history, but could be the center of a different version of America.

That’s also part of it, slipping into that vernacular of Boston history. Families that come to learn about Samuel Adams and the Boston Tea Party can also learn about Thomas Morton and this alternate vision of what America can still be.

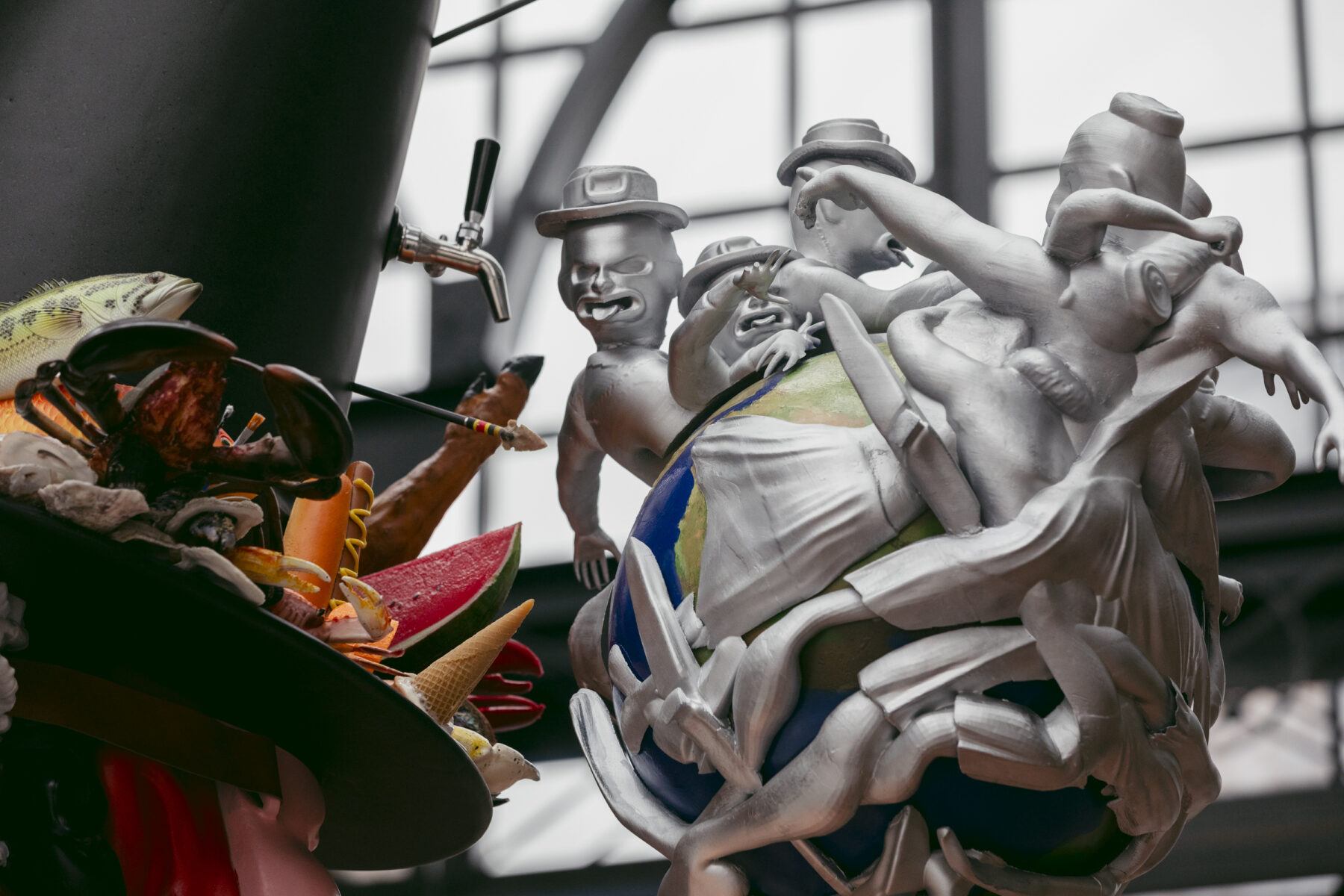

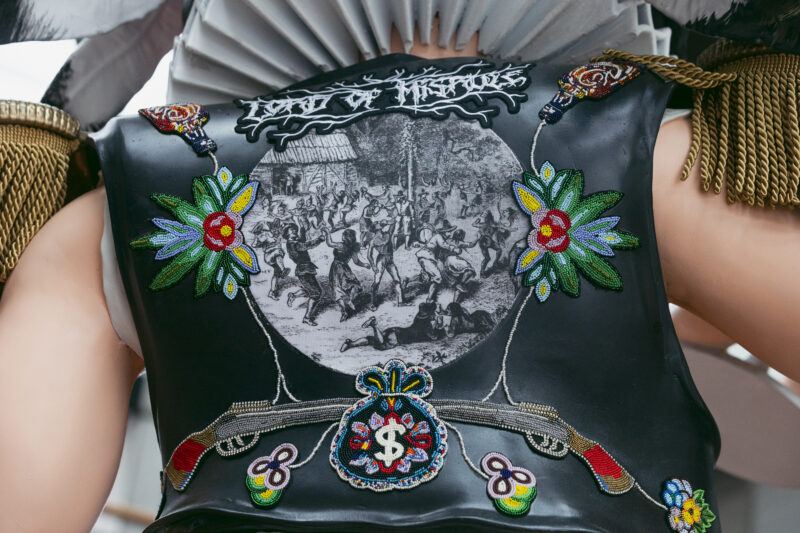

JP—Material Monument to Thomas Morton is an honoring monument or counter-monument to Thomas Morton, who was an apparent Native sympathizer, all-around confounding figure, and speculative precursor to the later acts of playing Indian at the Boston Tea Party.

Thomas Morton, being this kind of shadowy figure, was interesting for us to look at as a site upon which other representations of Natives might be projected back onto, increasing the visibility of this dynamic and its complications. We’re also looking at monuments and mascots as this mode of first comprehension of ‘Nativeness’ itself by non-Native people and how that has the possibility of continuing erasure.

There’s also a practice of shame or ridicule poles where I come from, which are made to commemorate figures who have not paid a debt. They’re only taken down once that individual or clan has made moves to complete the debt payment. But this is, in some ways, a shameless pole to Thomas Morton.

ZK—There’s the monument itself, but then there’s the historical plaque next to it, with the lesser-known history of Thomas Morton.

On the plaque is also a quote from the Austrian author Robert Musil, “There’s nothing in this world as invisible as a monument,” referencing how, by their very nature, monuments become invisible. They become a facet of the environment that no one really sees, and Boston has so many monuments of that kind.

Part of our intention was to work against that. Material Monument to Thomas Morton is garish, outlandish, colorful, absurd, and fun. It attracts a lot of attention, but still, some people walk by like it’s any other monument, even though it’s kind of hard to ignore.

AK—In our practice, we’ve been really engaged with the discussion around monuments and what to do with problematic monuments. As Indigenous people and artists, there’s some hesitancy around erasure and removal, for both conceptual and obvious reasons. Sometimes, the removal of representations of Indigenous people that are problematic might have been the only representation of Indigenous people within public spaces.

Michael Taussig’s idea of “Additive Defacement” was critical for us when thinking through monumentality and the propaganda of monuments: the idea is, instead of erasure and removal, there could be an additive approach, you can keep adding until the monument becomes something else.

That’s a heartening and meaningful concept to us, and something that we actually tried to put into practice with this specific sculpture, with the additive components of different cultural symbols, archetypes, and stereotypes. To continue layering, until there’s a different meaning that couldn’t be articulated with just another monument to a colonial era white guy, even though that is what it is. Through our additive defacement of that image, hopefully, it becomes something else entirely.