Kayla Anderson: How long has documentary been a part of your practice?

Morehshin Allahyari: All my practice, in one way or another, has been about storytelling and documentary building. From ages 12 – 15, I wrote a 384 page novel about the life of my grandmother, which was published in Iran when I was 16. My father’s family was from Kurdistan, and after my grandmother passed away, I made him take me to the village that she grew up in. I went around talking to different people and recording whatever they remembered about my grandmother. When I think back on it, I realize I’ve always been interested in ways to document social and political issues, performing archival work through the use of technological tools and processes.

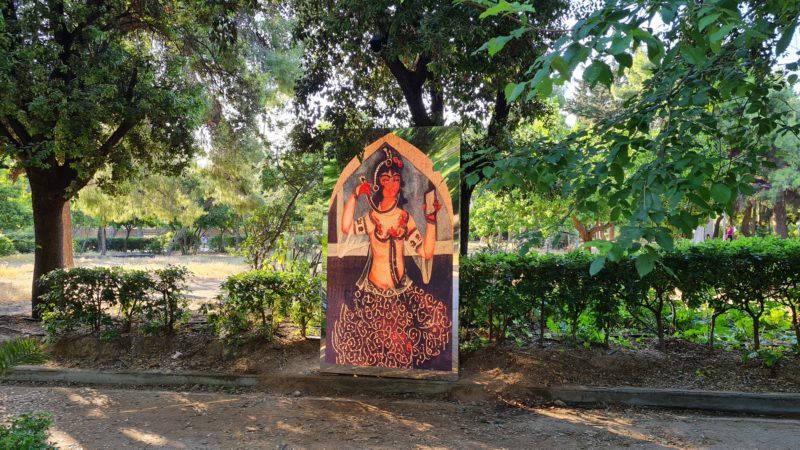

In both Material Speculation: ISIS and She Who Sees The Unknown, I was interested in reworking or reshuffling history. Re-figuration for me is about the reinvention of material forms, as well as preservation. It’s an act of going back and retrieving the forgotten or destroyed histories to re-imagine much needed alternative narratives.

Can you give me an example of how refiguring happens in She Who Sees The Unknown? Perhaps in The Laughing Snake?

In the original story, The Laughing Snake goes to cities and towns killing people, until someone comes and holds a mirror in front of her. When she sees her reflection, she laughs for days and nights until she dies from laughter. But in my re-figuring of the story, I don’t see this act of death as a position of weakness, but rather as a position of power, in which she takes agency over her body, her image, her reflection in the mirror. And so the new story I tell about her connects to the idea of embracing your body as a woman. It connects to my experiences growing up in Iran, and the collective experience of women thinking about sexual desire, street harassment, and different forms of patriarchy that control the way women deal with their bodies in both religious and societal contexts. I embrace the monstrosity of these figures. Instead of seeing monstrosity as negative, I see it as a place where I can turn around power structures.

In many of your works I see a kind of intergenerational storytelling. How does the idea of lineage or historical continuity play out in your work?

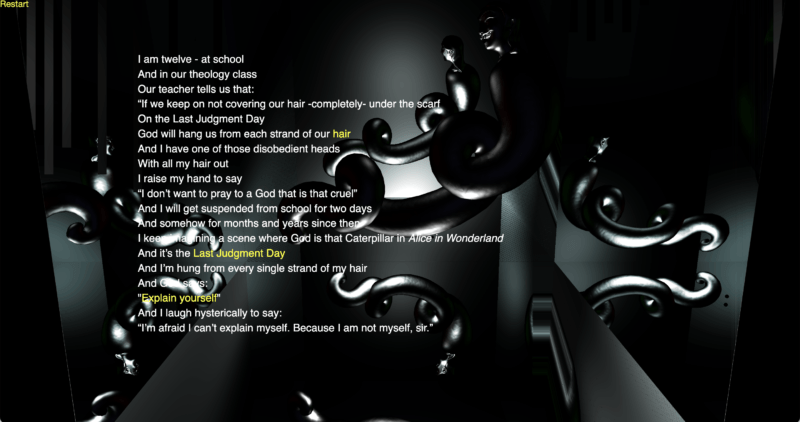

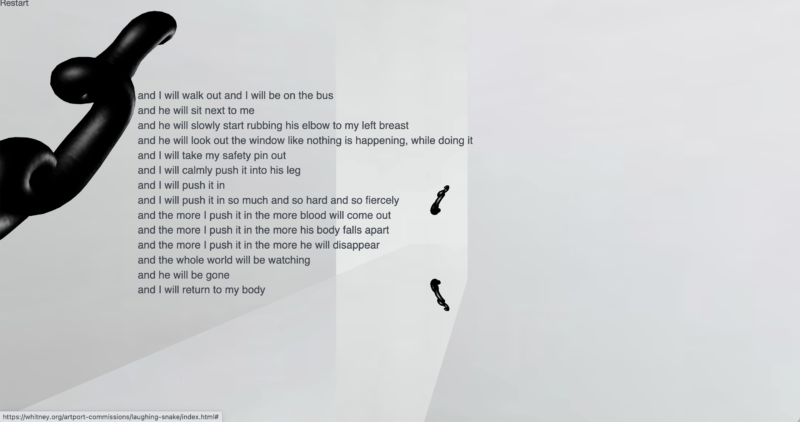

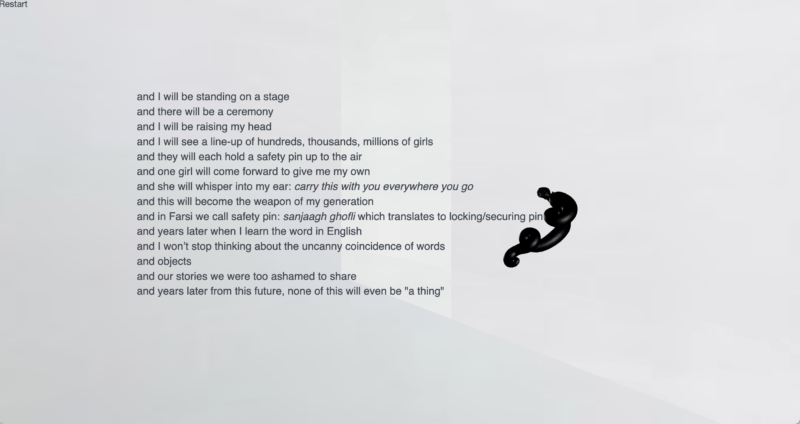

When I was writing The Laughing Snake I was thinking about how it has been almost impossible to get out of this patriarchal system. There is a story where I’m sitting on a bus, and a guy is trying to touch my breasts but pretending to be putting up the window. I imagine I take out a safety pin, something a friend told me to carry for cases like these, and when I put it in his body, he disappears. So I think of using imagination, and other ways of world-building, as a way to see into a future where you can interrupt a cycle. Stories like this have happened not just to me, but to all women in Iran. In my work, I always start with my personal experience, moving to stories from others, to imaginary stories where there’s more hope and possibility in imagining a future. In the case of The Laughing Snake, a future where women have come together to take back their power, their agency, their autonomy over their bodies.

Some of the techniques you use in the hypertext version of The Laughing Snake give the feeling of voices rising up together. We see that there is a lineage of patriarchal oppression, but also a lineage of struggle and resistance.

I made this in 2018, and now in 2022 we have the Jin.Jiyan.Azadi/Woman, Life, Freedom Revolution in Iran. Somehow I think this story, this future, is coming into real life practice, and that’s so powerful and important to witness. It’s one of the only revolutions that women have been on the frontline of: women and their bodily agency. We know that patriarchal violence and government violence is still very real and very harmful. Right now, as we do this interview, there is daily news of arrest, torture, and execution of protesters and activists in Iran. All these tactics are about gaining control over your body, mind, and life.

But in the same way that I write hope into a story like The Laughing Snake, I want to remind us that the word “life” is an essential part of the Woman, Life, Freedom Revolution. A life against hardship, oppression, inequality, harm, and death; a life of livelihood rooted in freedom; freedom to freely be and become; and last but not least, autonomy over that life and freedom. I see so much possibility and potential in the words and ways of this revolution.

In this sense, I see your work as a way of taking back control over narrative – the ways that stories and histories are told.

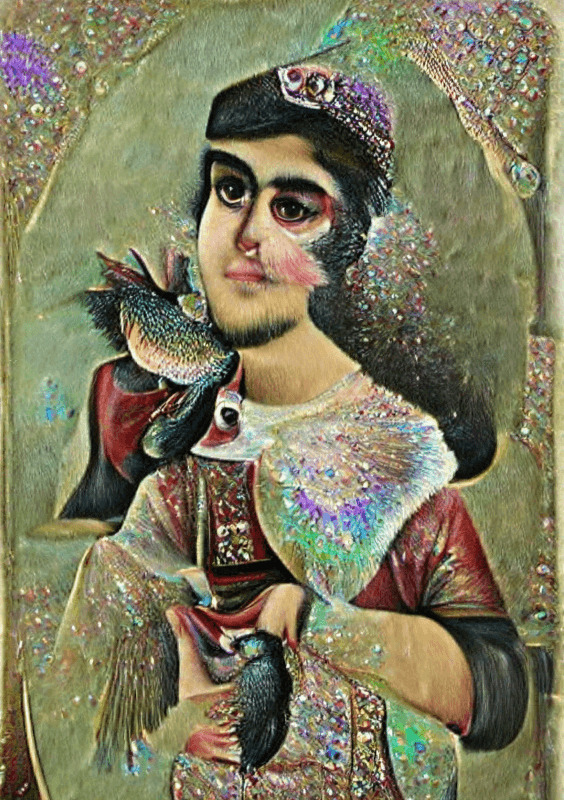

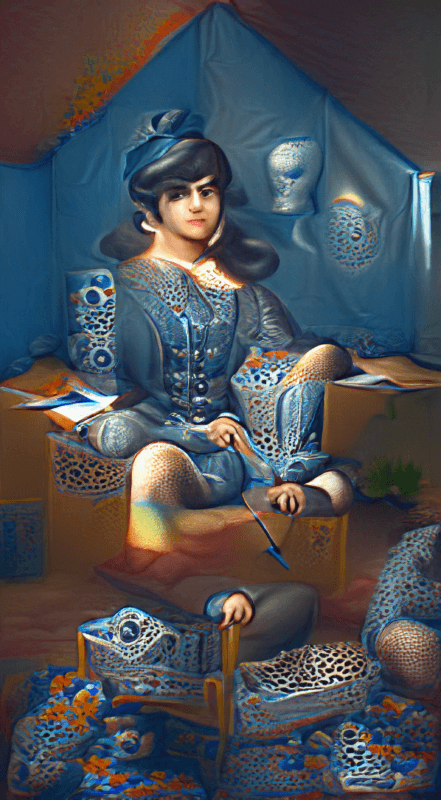

Our world becomes so small when we only understand ourselves through the context of now. History allows you to put things in a context that is much bigger than yourself. But history always comes with the power of those who have had access to telling it. For example, when you think about definitions of queerness from a Western perspective, there is a lot of order and categorizing of identity. But looking at the history of the Qajar Dynasty [1789-1925] in Iran, it’s amazing that what we know as “queerness” today was ordinary. Intimate same-sex relationships were natural. The relationship to beauty and gender was much more fluid. 350 years later, that’s not what we understand about our cultures, due to colonialism and oppression. In my piece Moon-Faced, I work with an AI system, feeding it different visuals and sentences, and asking it to undo the loss of visual representation of this queer culture: to repair this history of colonization.

That sounds like a very tangible act of futuring. Can you talk about the role of sci-fi in your work?

Growing up in Iran, there was a very interesting absence of sci-fi as a critical genre, from movies to literature. I’ve been curious about what that means. Not from a top-down approach like “we don’t have this, so there’s something wrong with us,” but why don’t we have it, and what does that mean about our relation to the future?

I’m currently working on a speculative documentary film project, where I’m looking at scientific tools and technological devices that were invented in the Islamicate regions. I’m looking at the history of ways we saw into, affected, or used different methods to predict the future. I have five female scientists, future tellers, and historians that activate these tools to discuss their history, but also use the tools to imagine possible futures of the Middle East. The experts in the film are from Egypt, Iran, Palestine. I’m trying to create, as much as possible, a wider spectrum of ways of seeing and imagining us into the future.