Gabe Beckhurst Feijoo – One of your recent projects, Lake Tai (2022-23), was presented at Prada Rong Zhai, a restored historic residence in Shanghai. The exhibition “looks to” Lake Tai, and I was very interested in this sense of “looking to” rather than seeking to represent the conservation efforts at Lake Tai, which are often upheld as exemplary. Several of the works in the exhibition activate the lake’s historic transformation through senses such as smell. I’d like to ask you about this sensory excavation of Lake Tai, particularly when the visuality of ecological degradation is often figured as being in crisis–so unwieldy it exceeds conventional methods of visualization. What were some of your considerations here?

Michael Wang – Lake Tai is a large, shallow freshwater lake just west of Shanghai. It was seen in classical poetry and painting as a tranquil site of extreme beauty. With the rapid urbanization and industrialization of this region in the 1980s and 90s, the runoff from industry, urban waste, and agriculture caused what has happened in many lakes around the world. It caused the buildup of nitrogen in the water and resultant blooms of often toxic algae, including cyanobacteria. More recently, there have been massive efforts to remediate the lake, including major efforts to remove that algae. I was very interested in that whole story and came to think of the lake–which is upheld as an environmental success story–as a cyborg entity. It’s this seemingly natural thing that is actually intensively managed by all kinds of technological plug-ins. Water is even redirected from the Yangtze River to replenish and recalibrate the waters in the lake. I wanted the work to express this level of engineering not just representationally, but to somehow be a part of those systems.

Many of the works use algae that have been extracted from the lake and then contained within sculptures. The Lake Tai area is a site of rich artistic tradition. Taihu stones (stones from Lake Tai) are icons of Chinese art. These are the twisted stones used in traditional Chinese gardens. I recreated the form of those stones using organic waste products from the lake. Many of these “stones” incorporate the algae from Lake Tai algae blooms. I was able to work in cooperation with some of the remediation operations on the lake to use the algae they’ve been collecting. I wanted the sculptures to feel like they plug into and have this relationship to the lake and to these technological agents of remediation. Materially, they are part of those chemico-biological systems. My hope is that in a very small but maybe measurable way, they’re playing an active role in that recalibration–even as static sculptures. They’re sequestering these organic wastes outside the chemical processes of the lake.

To return to your question of smell, it’s true. The works that are made of algae maintain this fermented smell of the cyanobacteria. It’s not strong, but it’s there. There’s a sculpture that recreates a traditional fishing boat full of the forms of the hairy crab, which was historically harvested in huge numbers from the lake. But the 3,500 crab forms are actually cast in algae. The smell of the slightly decaying, fermenting algae comes from the connection to that organic material, a material that comes from the lake but is now displaced into the exhibition space. It’s part of a process of connecting the lake to the sculpture and to the body. Smell isn’t like sight–which always maintains a distance. Scents signal that materials are being absorbed into the body itself.

Could you speak about how the other industrial products or byproducts in the exhibition correspond on a material level?

There were so many ways that I wanted to connect materiality to the lake and to that region. All the materials have some relationship to the intertwining of nature and culture at the site where the show was exhibited in Shanghai. Shanghai has a very specific relationship to the lake. The hydrological system of the lake extends to Shanghai. Suzhou Creek connects Lake Tai to Shanghai. They really are part of one continuous water system. A lot of the stories I examined were about the connection between the site of the exhibition and the distant site of the lake that in some way Shanghai relied on. This relation was reflected in the story of the building the show was installed in, which was the home of a turn-of-the-century industrialist from the Lake Tai region. He was operating between his hometown of Wuxi (on Lake Tai) and Shanghai. His businesses were connected by this waterway. Shanghai was the trading city and Lake Tai, linked to the Grand Canal, was very well connected to a larger area inland. This was a site where raw materials could be received, then sent to Shanghai for processing. These relationships triggered both a material and formal exploration that was also about trying to traverse pre-modern histories, the local effects of industrialization, and a more or less post-industrial present.

There’s a series that takes on the history of the creek that connects Lake Tai to Shanghai. Suzhou Creek became an area of factories and warehouses dominated by standard concrete and steel architecture. Many of those structures were torn down in the last decade and I wanted to make use of this discarded material. I made a set of works in the form of Chinese fir, which was a natural material that was used to hold back the flood waters of Suzhou Creek in ancient times because it’s a waterproof, rot-resistant wood. But I remade this tree in recycled concrete and salvaged steel rebar from Shanghai demolition sites. The works record a double disappearance–of the ancient embankments of Chinese fir, and of the industrial waterfront that replaced them.

This brings us to a question I have about place as an axis for your work. Several of your projects explore specific avenues in conservation practices and invite the question of an ideal conservation state. The ethics of using transgenic methods in de-extinction work, for example. Or, with Lake Tai, exploring a site that has long been held up to an aesthetic ideal and how conservation efforts seek to “return” us to that state.

So many of my works are highly site-specific, but site can mean so many different things. It can be a literal kind of geography, but it’s often that plus all of the different kinds of relations that condition a particular context. I’m thinking about a work in which I recreated a living version of a Carboniferous forest (the Paleozoic forests whose buried remains formed coal) that was installed in a disused coal gas plant. Here, site was about natural historical and technological relationships. A fragment of a coal forest returns at the very site where the remains of these forests were vaporized. The living plants now recolonize the ruins of fossil fuel infrastructure.

Lake Tai is tied to the specific cultural, natural, and artistic histories of that particular region. It’s intertwined with the different forces and histories overlaid there. For me, an artwork never really stands alone. It is always linked up to conditioning forces. In that way, the line between the work and the larger world becomes hard to define. That is how I hope people encounter the works too, in that the work is a condensation of certain effects that are at play in the larger world.

How do you navigate in your work between the recreation or replication of what you describe as a “piece of a lost landscape” and something like “site reform,” as gestures toward remediation?

There’s something very ambivalent about my relationship to conservation and its histories. This becomes especially relevant in works where I’m invoking a pre-industrial past or where I’m looking at local extinctions. With Lake Tai, I had to grapple with the entrenched aesthetic vision of the pre-industrial lake as something pristine. I’m often trying to somehow balance–or question–this urge to return which I think goes beyond nostalgia. Sometimes I am trying to balance the culturally rooted meaning of a place while also looking honestly at what it really looks like to try to return to a primordial state–Lake Tai as this highly-managed, technologically-enhanced, cyborg body, for example.

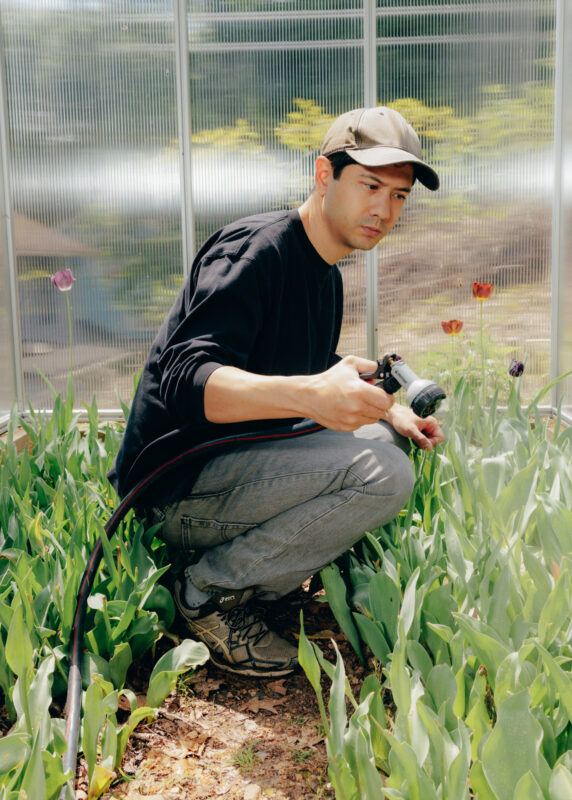

The works often partake in this duality: they are efforts to restore what has been lost, while also revealing that as an impossibility, foregrounding the chain of effects in the present that any project of reversal sets in motion. In a work like Extinct in New York (2019), where I brought back to New York City a selection of plant species that had been locally extirpated, I’m trying to make visible the vast energy and technological requirements needed to achieve an act of restoration on an infrastructural scale. The plants were maintained in lighted and ventilated greenhouses and attended to daily by curatorial staff. These living beings return to the city, but on life support. That, for me, is a way of foregrounding both the necessity and the impossibility of homecoming. There’s no easy return. In my research into the history of nature conservation, I have found it linked, at moments, to nostalgia-fueled violence that exceeds all bounds. At the same time, nature conservation has provided us with some of the most deeply considered ethics of care. I’m always looking for a place where I can somehow feel like I’ve balanced these conflicting attitudes, feelings, and effects. I am very interested in foregrounding practices of care while also showing care’s mechanisms of control and the often violent uprootings and displacements that can be the consequence of that care.