Murtaza Vali — body of work, the title of your recent mid-career survey at MCAD Manila is a wonderfully succinct description of the many complex questions your practice raises and engages with. It is, like your art—both your signature untitled “brick paintings” and your forays into other media such as sculpture and video—simultaneously intentional and generic, semantically opaque yet multivalent. Can you elaborate on what “body” and “work” mean in relation to your artistic practice?

Maria Taniguchi — The process for making the “brick paintings” is relatively simple: the groundwork is done, a drawing is made, and then each brick is painted one by one. I have always thought that on a meta level I was making ‘work about making work.’ In this configuration, to materialize also means to embody. One way to describe and elaborate this idea would be to mention an aspect of time in the paintings that belongs to the everyday. Each brick is a notion of time that, extended over the body of painting, is encoded into structure by a deliberate act of repetition. This repetitive action, because the scales of time are involved, is probably what precipitates the need to call it labor, on the part of people who encounter my work, and increasingly on mine. Labor also implies an eventual breakdown, or a gradual breaking down of a body. In the paintings I see this bodily expenditure as fragmentation.

MV—How did you arrive at this formula?

MT—The process has been heuristic. The first painting was intuitive, the form arrived almost by accident, and the next ones were a slow process of uncovering what was important for me at that time.

MV—Interestingly, the precision of the abiding structure or system, which one might think would enact discipline or control or identity, paradoxically achieves the opposite: enabling freedom, chance, and contingency to reveal itself.

MT—I think that once I had decided on some specific conditions for the paintings, I realized that I didn’t have to try so hard to control the outcome. I did try once or twice to generate something with certain methods of composition, but that didn’t get me anywhere. Through this, I quickly learned about what ‘process’ means, everything started to fall into place after that. There is always a drawn pattern which is one of the conditions that doesn’t change, and everything inside of that is up to chance. You could say that, in a way, chance is painted into pattern. What happens next is a contingent surface.

MV—What effects do the repetitive actions and gestures of executing a “brick painting” have on your body and mind?

MT—Now that it has been a while, there is a literal type of breakdown but nothing exceptional. It’s the kind of bodily breakdown that eventually happens to anyone who routinely performs repetitive gestures, movements, or any type of manual work or sport. In the case of people who make paintings it’s almost always the muscles and tendons around the working hand and elbow that start to make themselves felt. Painting is a pleasure as much as it can be physically and mentally difficult. I have to admit, some of the cliches are true.

MV—What draws you to repetition as a methodology or as a mode of mark-making? As a working logic, it bears a relationship to both form and structure and to time.

MT—Actually, it was not so much about the pattern at the start. I liked that each small, individual rectangle reminded me of how an actual brick is made: clay is crushed and kneaded with some water, then pressed onto a mold. I liked sensing that physical compression and how this could extend conceptually within painting.

MV—While the overwhelming majority of the “brick paintings” use matte black paint, you have experimented occasionally with other colors or tints. Does this chromatic shift precipitate other shifts? In your mind, does it change what the work does, how it is received?

MT—Small amounts of certain colors have been making their way into the paintings for some years now. These are easier to distinguish between individual works in larger groupings of paintings. I wouldn’t say it’s a change in process, since I periodically untether and make paintings that step away from the general body of work. I think when people familiar with my work see these paintings looking a bit different, there’s always some idea that they are a kind of progression, but I don’t see it that way.

MV—Scale plays an important role in both how your work is produced and perceived. Scale, of course, determines the time required to finish a painting, which also affects its facture. Shifts in scale and orientation also influence how a spectator engages and interacts with a particular canvas. How do you determine the scale of individual works?

MT—The scales were determined in the first few years. Most of the paintings were made at home, so the larger ones were determined simply by the length and width of my living space. In exhibition spaces, this width becomes height, but it’s not about verticality when I am in the process of making them. They inevitably had to happen within a space for living as well as working. In retrospect, I’m talking about living and working as two separate things, but it’s never like that when you work where you sleep and eat. It was in this type of environment that most of the conditions for this work came together, and I think it’s important to think about them in the sense of this early formation.

MV—You began the “brick paintings” in 2008. At this point, you have been repeating the same conceptual gambit for seventeen years. I admire both the obsessiveness and the disciplined mindfulness of this commitment, which reminds me of Tehching Hsieh’s year-long performances and On Kawara’s quotidian conceptualism. It definitely has a spiritual dimension to it, repetition as ritual, like a monk who recites the same prayers and mantras everyday. Do you think you will ever stop making them?

MT—The question of a termination point always comes up. At this point, it’s a type of self-generating system that paradoxically requires my body and my input in order to go on. It would be cheesy to say that it ends when I die, but that’s probably how it will turn out. That is just a function of the work’s conditions, and it does not have to do with obsessive behavior. I feel like I have to laugh after saying this but, I am not obsessed with painting bricks and I don’t have to do it out of pure compulsion. Maybe there’s a little bit of an urge, tied to intuitive impulses, but I do it more out of curiosity—what happens next? Even after a hundred paintings, there is always the feeling of renewal.

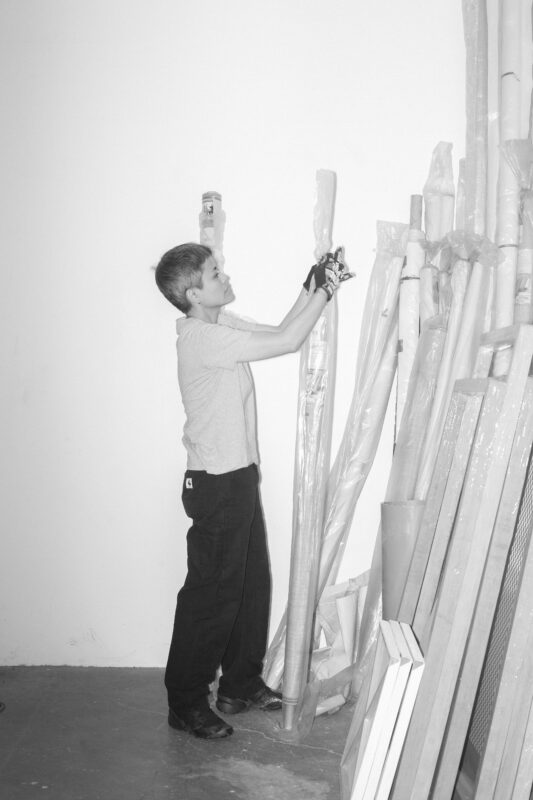

MV—Your wonderfully sculptural metaphor for the process of painting individual bricks reminded me that you trained in that discipline. The MCAD exhibition also includes Runaways (2024), a series of wooden sculptures of circles and lines that are as rigorous and restrained as the paintings. Can you describe the sculptures and reflect on their relation to the paintings?

MT—The sculptures are a little bit more difficult to talk about at the moment, although I have been working on various iterations of them for about five years now. There’s a bit of biographical memory and a bit of computation inside of them. In some places, the Philippines being one of them, there is a determination to what your mother craves while she is pregnant with you. In the Philippines, the term is ‘lihi.’ The craving is not just for food, it can also be for the proximity of something else, like objects or even people. It is believed that certain qualities of the craved food or object are then somehow passed on or encoded into the child. The sculptures are a cipher for this process. The wood is made of lomboy wood (Java plum wood). My mother used to tell me she ate a lot of this tree’s fruit when she was having me. I associate this gestational image with a color, since lomboy fruit stains your whole mouth a deep blue-violet. For me, there is also an association here about blending and about the porosity of the idea of a body.

MV—Despite their minimal appearance, which projects a sort of Modernist autonomy, I am struck by how the repeated mark and action used to build the “brick paintings,” and your continuing insistence on making them yourself, might alternatively position painting as a type of craft. This perspective seems to be supported by some of your early video works such as Untitled (Dawn’s Arms) (2011) and Untitled (Celestial Motors) (2012). While the former focused on the hands of a Filipino sculptor carving a replica of George Kolbe’s Der Morgen (Dawn) (1929), the latter showcases the craftsmanship and skill that goes into the production of a jeepney. What are your thoughts on craft, in general, and specifically in relation to your own practice?

MT—The hand is always there to reiterate that this system is tied to life. While it explores its potential in seemingly non-human scales, there is no guarantee of perfection or infallibility. The history that is encoded in the traces of hand-work as well as the vagaries of objecthood that make the craftsperson’s presence felt guarantees a connection with a particular sense of time that is increasingly becoming more important.

MV—Similarly, the video Figure Study (2012), a just under forty-minute long black-and-white video of two men digging up earth in a dense forest is a deadpan document of labor, suggesting a parallel or equation between their manual labor and your artistic labor. What are your thoughts on labor, and on your “brick paintings” as allegories for other types of labor?

MT—In the paintings, labor manifests as a durational act of repetition, while the videos often frame labor in action or its traces. To me, the visibility of labor or ‘work put in’ denotes a transparency in the system. Without giving away too much, this transparency is mirrored materially in the process of painting. Although the process and, to some extent, the system is apparent, the paintings are by no means transparent as objects. Labor in the paintings is part of an operation that has to do with embodiment and this is related to the answer to your first question about the “body” and “work.” To my mind, this cyclical and often intensive process allows several transmutations to occur. For example: labor is transmuted into time, time is transmuted into a volume that might be called information.