In the Studio

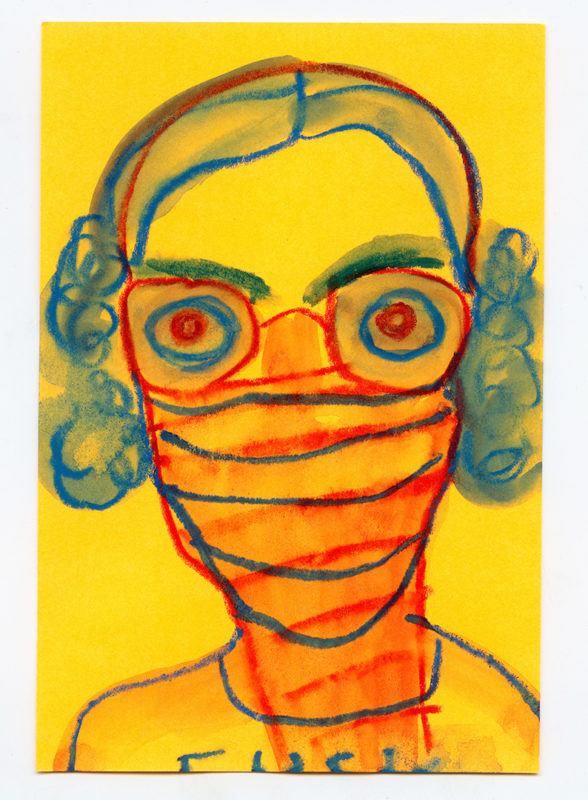

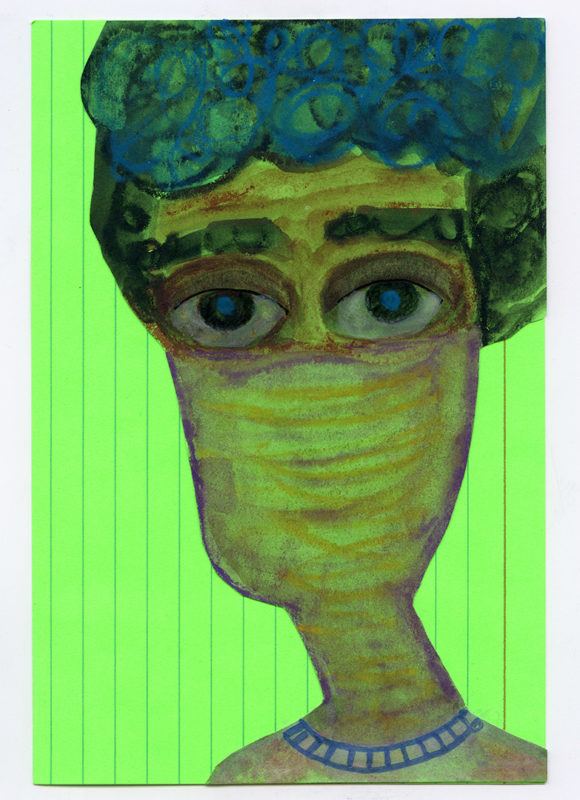

Through meticulously labored paintings, Laylah Ali investigates the disconnect between the human body and freedom.

Art21Television and cartoons have been noted as influences of your work. You’ve also mentioned that television and film have the possibility for wider social impact, more so than art. What conversations does film address that art cannot?

Laylah AliTelevision was definitely an influence on my visual sensibility growing up—I watched a copious amount of TV as a kid in the 1970s and 1980s when TV shows were more widely shared and experienced. In some ways, the TV I grew up with still often referenced stage sets, which I think became imprinted in my brain. I feel like one was then more often watching head-to-toe bodies—I think about the Carol Burnett show or even cartoons like Road Runner—there were floors or ground shown. It is also useful to remember that TV went off the air at a certain time of night, usually with the playing of the national anthem, sometimes showing a moving image of the U.S. flag, and then gray static would replace the image. Television rested at night, and reminded you that it was connected with state control.

But mostly the relevance of the moving image has to do with access and availability, which fine art is terrible at, and TV and film currently much better at. So, if you want to speak to a wider audience, a less predictable audience, then TV and film seem a much better choice right now. I wish that were not the case, but the core of the fine art world remains mostly uninterested in broadening its audience. The $25 entrance price of a place like MoMA, as well as their extremely limited free entrance times, speak volumes about this.

What prompted you to use cartoon-like figures to depict sometimes graphic and violent themes?

I started by making more realistic figures in graduate school, but the leap to allegory was harder with realism involved. I wanted the figures to exist in a parallel world that the audience had access to but allowed for some distance.

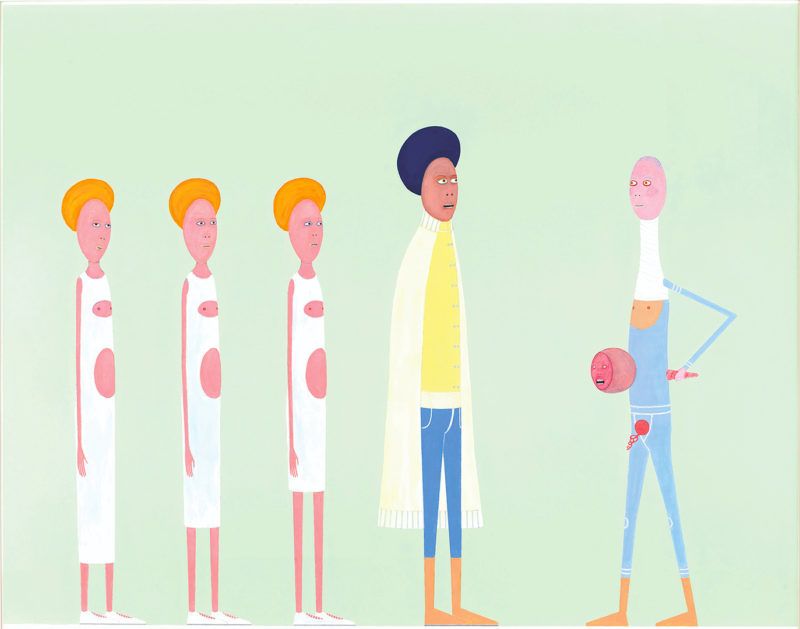

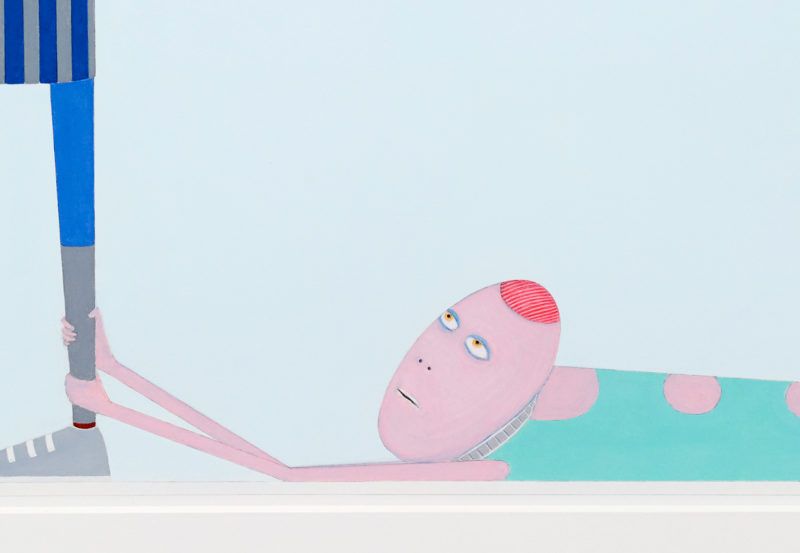

The poet Lillian-Yvonne Bertram used a term about my figures that I really liked. Lillian-Yvonne called them “askance/askew humans.” Their physical forms are mostly referencing human bodies but they are also flat and deliberately drained of their three-dimensionality. What they do and what their stories are have everything to do with people. But, for the most part, in my paintings, I deliberately don’t operate in the world of realism. I want my figures to have some possibility of freedom and independence from what traps and binds us in real human bodies.

What information do you glean from hand gestures? And what other gestures or motifs inspire your work?

Hands, hand gestures, eyes, the running, walking or fleeing body, ubiquitous wounds. These all still are important to my work. I used to clip and file newspaper articles because it was a way to understand visual tropes of power and suffering. I wanted to document the way different races, nationalities and ethnicities, etc. were allowed to function in the public arena, via newspaper photos. And also such photos were useful sources for specific gestures—the pointed finger of a dictator, for instance. But those tropes are so enduring that I didn’t need to collect those images anymore.

The body can be reduced to its ability to labor or perform certain functions, and yet there is usually something else occurring that belies what is being enacted. Hand gestures and eyes are a place to look for other sorts of information that escape from what might be the obvious, or imposed, narrative.

I return to the human body because I don’t ultimately understand it. And the body always invokes a larger context even if you don’t place it in an exact setting. The often unexpected or jarring experiences I have had in my own body have been the gateway to a more wide-ranging exploration.

How do you assign colors to your figures?

Because of the world we live in, and the inescapable legacies and existence of racism, there is no way to engage with color on figures, even fantastical color with utopian leanings, without referencing, either knowingly or unknowingly, the different histories of racism. I try to do so knowingly. Color has optical impact for sure, but that can never be separated from a larger historical context in the figurative realm.

Figures in your earlier works are often androgynous and seemingly genderless. Has this taken on new meaning over the years?

I have definitely become more interested in how I gender my figures. So, generally, as the years have passed, I have been interested in making characters/figures who are more complex and difficult to name in our very binary English language. Essentially, I have always worked in the visual realm because I have not been able to express the complex combinations of human identity and existence —which include race, gender, sexuality amongst many other aspects— except through visual means. Unlike in my Greenheads series, the figures in the Acephalous series are gender conscious, as well as being potentially sexual or sexualized. Genitalia make an appearance. There is also actual racial difference amongst the characters. There is hair.

I remain interested in what is obvious about bodies as well as what is covered up, the way that bodies can be manipulated and changed—and how they cannot. I am interested in how much can happen to a body, how much it can absorb, and what survival might look like.

You’ve described your work as psycho-political in the past. Does that still apply?

I still like that term “psycho-political” and it captures something about how I engaged with my Greenheads series.

But overall, I think that most everything I make is about the disconnect between bodies and freedom.

In my work, I think about how narratives of freedom and self-realization are this never-to-reach destination that we drink, and are sold, and that motivate and enervate us. Those narratives have extra weight and sometimes deadly stakes for, as many of us know, bodies of color, queer, trans, women’s bodies, people with disabilities, the combinations are many. Bodies that resist being externally named, that exist in places they are not supposed to exist, that claim space that they are not supposed to claim. I remain interested in examining the body and its different contexts, like state control over bodies, while devising escape hatches from the body.

How do you balance the tension between your methodical preparations and process and the sometimes unexpected result?

My own labor is imbued with tension because I am making my body work in a way that it does not want to work. My whole body resists how I make the paintings and what level of obsessive attention I give to them. It all sounds ridiculous when I describe it because my body and I are obviously one, though when I am making a series of paintings, it feels much more like a mind/body split with my mind directing and subjugating my body. I have a very different, more relaxed process for making drawings, which is not so perversely imbalanced. But the tension that is part of the painting process has a life in my paintings. I am resistant to my own process, but I am the boss of that process.

Has your practice evolved at all since we first filmed with you over fifteen years ago?

I think I am just more balanced as an artist, as a person. Meaning: I am more in touch with the core of what I do and the knowledge that this is a lifelong project with different iterations.