Kayla Anderson – How did the repeat pattern become a motif in your work?

Joiri Minaya – My mom owned a clothing store in the Dominican Republic (D.R.) from when I was very young. Visually I grew up surrounded by repeat patterns in fabric. When I was in the D.R. and when I first came to the U.S. I was working with ideas around gender and domesticity, and domesticity led me to decoration and home environments. I actually didn’t grow up with wallpaper. It’s not very common in the Dominican Republic but, as I started reading about the Caribbean, also partly influenced by European and American visual culture, I started thinking of it as a way to convey ideas about stereotypes and societal formulas that people conform to— societal patterns that I wanted to question. We all recognize these codes, regardless of where we come from, because we are all the product of a society formed by colonization and imperialism, the processes that made these images.

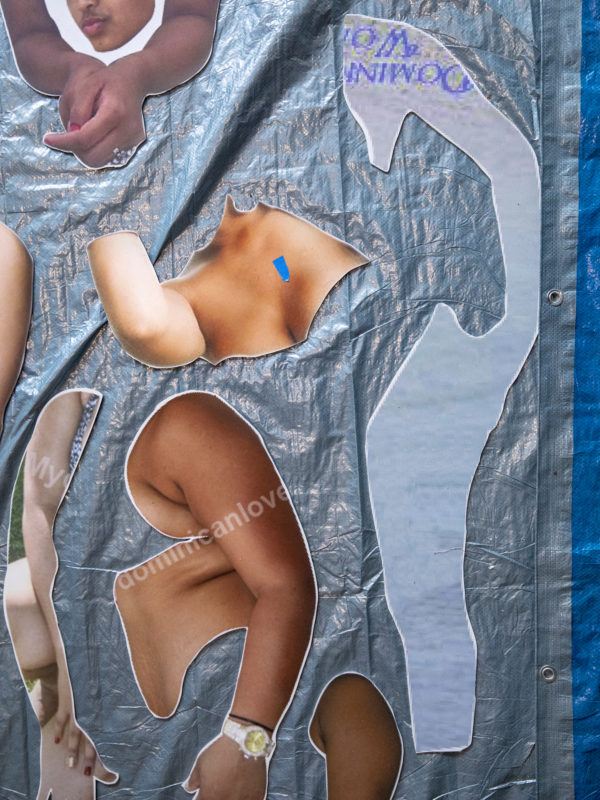

I was doing Google searches of “Dominican women” as a way to understand how Dominican women were represented to the world online through this label of identity. I started making collages with the images I found where I was denying the image of the woman, covering the image as a way to refuse or frustrate the desire to see that image: interrupting the process of consumption. I thought, I’m going to cover the image of this woman—this construction of the Dominican woman— with this tropical pattern, that is also a construction. Those collages ended up being source material for a body of work called Containers, where I started sewing bodysuits based on the poses that I saw repeated in the Google search results.

Is that when spandex came into the work?

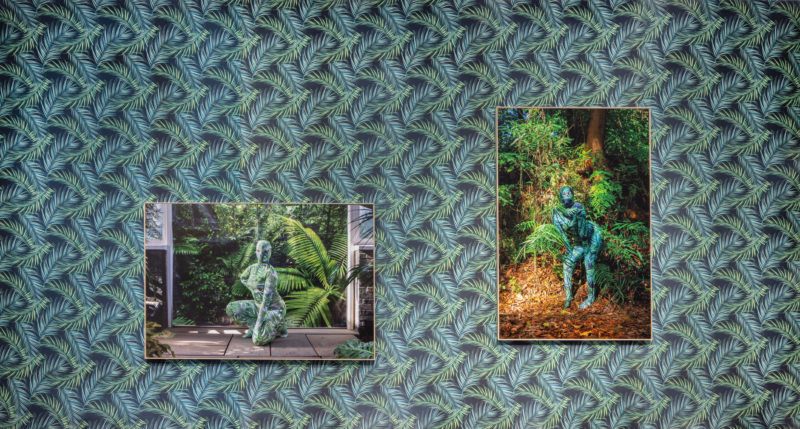

The first body suit was made out of upholstery fabric which was very constraining and uncomfortable! The first image was taken in an all-inclusive resort in the Dominican Republic. The spaces are constructed to look natural but it’s totally manmade. There was this concrete floor with planters on the side where I posed. Lying on the floor in this very claustrophobic upholstery fabric bodysuit was kind of terrifying.

After that I thought, I like this image, I like where this is going, but I’m not going through this experience again! I wanted to experiment with more specific poses from the search results. I decided to explore other materials and I realized that there was this whole production of tropical patterns in spandex. The patterns I was originally working with originated from the time when Hawaii first became a U.S. colony and they were trying to craft this identity around tropicality by producing patterns for what later became the Hawaiian shirt. These patterns were printed on cotton and upholstery fabric for Americans to decorate their home interiors. Now you have trends in yoga pants and bathing suits; the patterns have migrated to spandex for the sake of form-fitting leisure wear. I became interested in the materiality of spandex, the associations and relationships we have with spandex and the female gendered, feminized, body.

Can you talk about the move from collage to embodiment?

Part of the process is trying to understand these things on my own body. I read that trauma is a kind of repetition in your head, a pattern, in that you access it over and over again. Confronting a trauma in a controlled situation is one way to get over it. I don’t have trauma related to the Containers series per se, but I have experienced being objectified and associated with these images of Dominican women through my perceived identity. In Containers I make a controlled setting to confront that gaze. When taking the photographs, I’m often bound in the suit and I can’t move, so it’s intense on one level, but it’s also very comical and ridiculous, especially to see it from the outside. So I’m returning that gaze in a way that is very loaded, but also absurd.

For example, #6 was taken on a beach that was very crowded and everyone was looking at me. I imagine what it must be like to see this person covered up in such a strange way at the beach in this reclining pose. I wonder if it triggers something, a question in the regular Dominican person’s mind who’s on the beach that day, seeing me take the photo. Of course there’s also serious associations. #4, to me, is a direct reference to the odalisque figure, and thinking of how the history of Orientalism has been extrapolated to the Caribbean through that same process of colonization, how women are seen in very similar ways in spite of these two different cultural contexts.

It’s also a way for me to access ideas of sexuality that I might not be comfortable exploring in less protected ways. A lot of the poses are very sensual and suggestive. Despite the history of objectification, there’s a personal desire to embody these things to an extent. It’s something I think about when I see the image search results – I wonder, what are the levels of agency around this? Some of them are from online catalogs for men that want to date a Dominican woman on their vacation. But then I think of Instagram and how people are presenting themselves to the world these days. Containers is also in conversation with that trend in self-presentation.

What is the role of spectatorship in your work?

I find people’s behaviors fascinating. Sometimes I wonder, “Am I making this behavior happen, or am I simply drawing out a pattern that was already present” For instance, with the performance version of Containers, the selfies people took were to be expected and the very short fleeting interactions where the image was the priority. But there were also people touching the performers and standing in suggestive poses around them. That surprised me. It shows that the desire to make this kind of sexualized, objectified image is strong. It’s interesting to see that desire surface in relation to the extractivism that shapes touristic spaces, the expectations of performativity and labor from people in tropical locations. That desire appears even in that very contemporary, very common, gesture of snapping a photo. It’s a gesture that we’re all implicated in.