Jurrell Lewis – What about the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima and its aftermath drew you to it as a subject for photography?

Hiromi Tsuchida – In 1975, when I became a freelance photographer, I became aware of Hiroshima as a subject to record. I perceive myself as a documentarian, and I was looking at things from that standpoint. The damage from the atomic bomb was something very new in the history of humanity. It was a big event that humankind had never experienced before. So to be a Japanese photographer in Japan and not approach this subject would have been unacceptable. That was how I felt.

As a documentarian, my role is to face reality on the ground, where it’s happening. I pick out the phenomena that are occurring and what is being thought about. My work is then taking these things that have been picked up and editing and presenting them based on my thinking. In most cases, for me, this involves shooting societal phenomena to shed light on them.

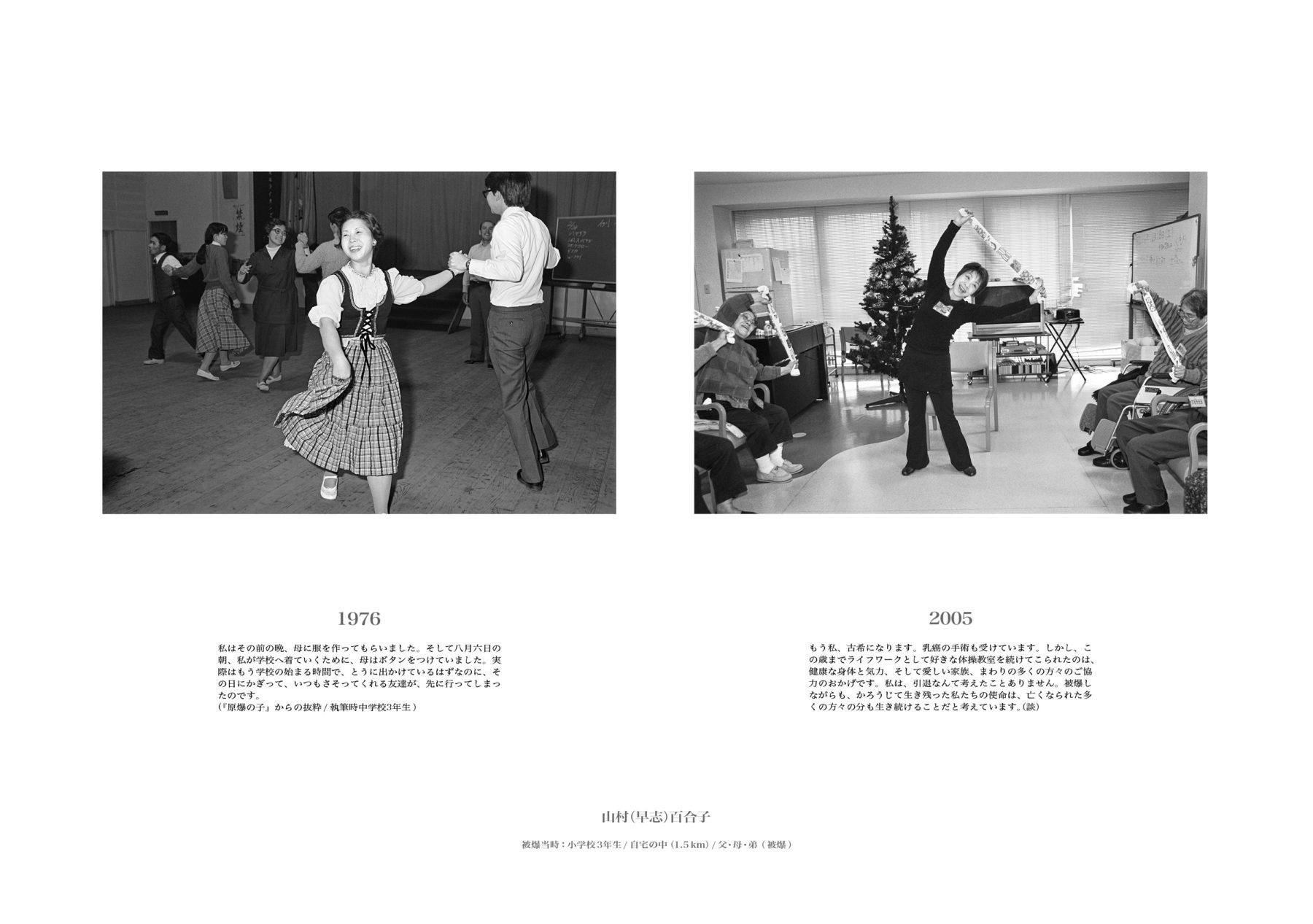

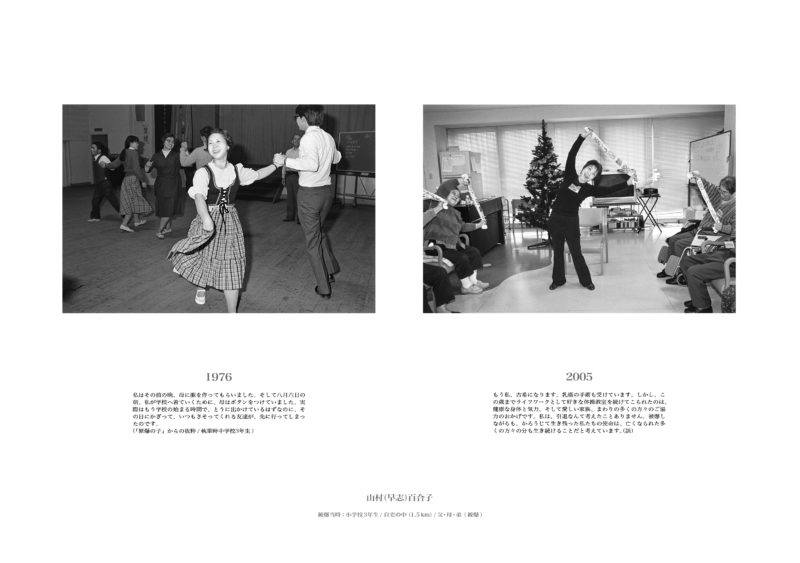

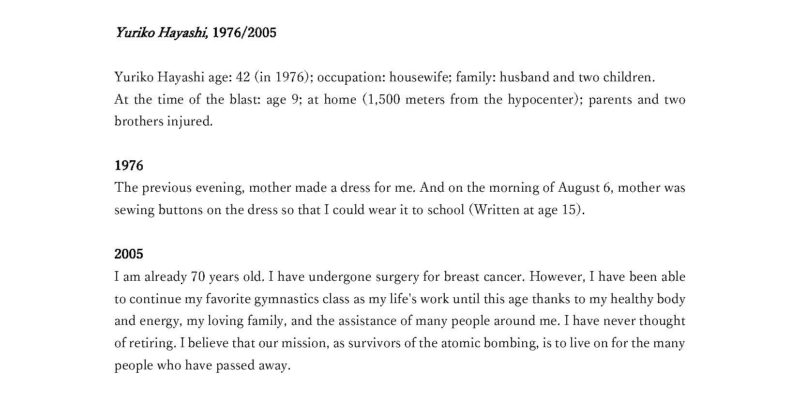

Something interesting about the photographs in your series Hiroshima 1945-1979 depicting survivors of the atomic bomb, like those of Yuriko Hayashi, is that the subject is not positioned as being emblematic of trauma or as a survivor, rather Hayashi-san is dancing with a wide smile on her face in both of these photographs.

How did you navigate creating this sensitive depiction of your subjects, not as a representative of this trauma, but rather as representative of each of us in our vulnerability to this type of catastrophe?

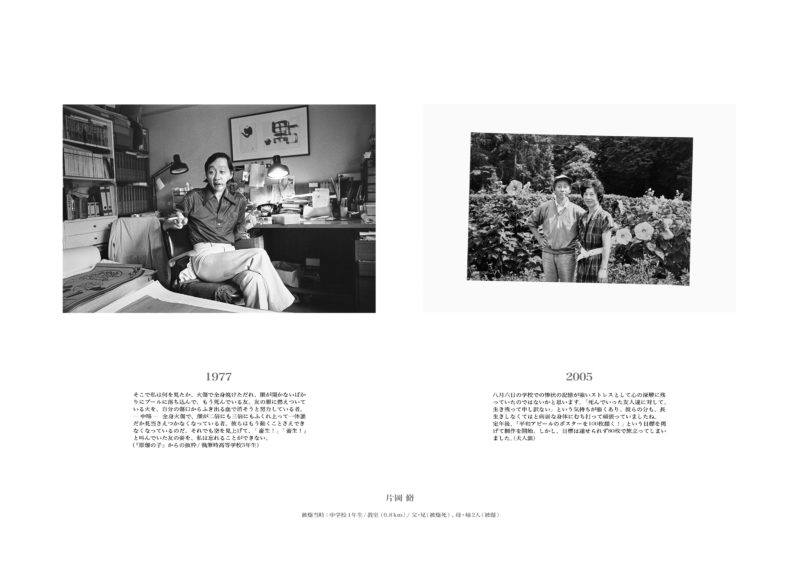

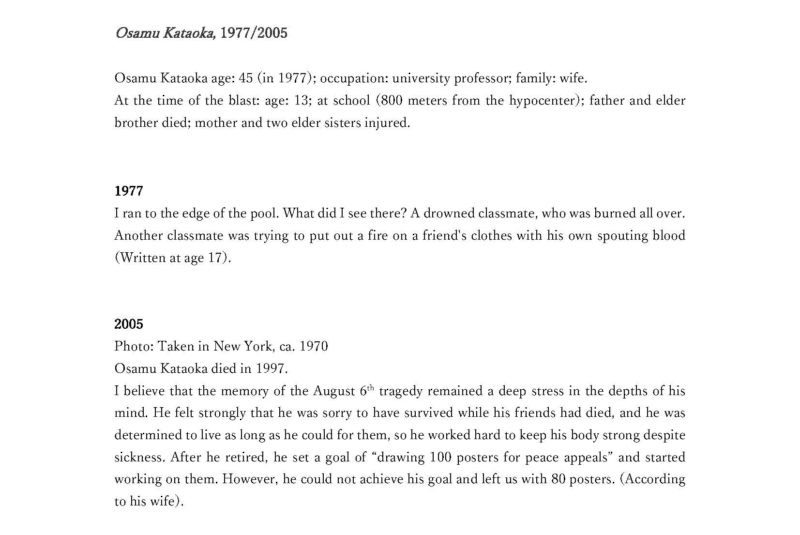

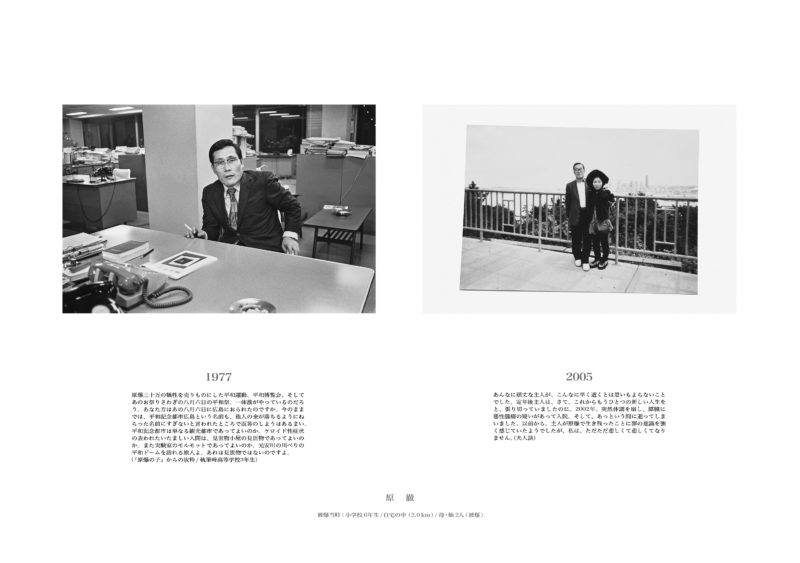

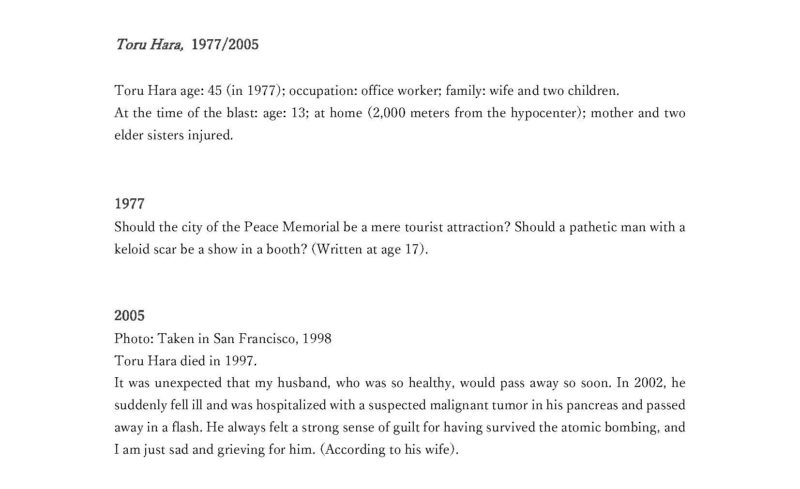

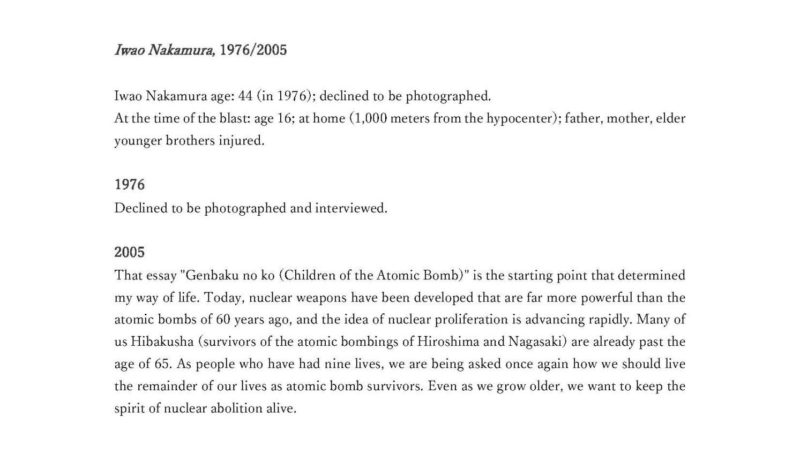

With other photographers photographing atomic bomb survivors, there was a strong tendency to take tragic portraits. Through this, they were trying to express the severity of the atomic bomb experience. My perspective was different; in most cases, I wanted to portray survivors as they wanted to be photographed, based on the requests they had conveyed to me.

You mentioned Hayashi-san, who dances for both work and pleasure. She requested that I photograph her enjoying herself, giving a dance lesson, so that was the photo that I took. She said to me, “I’m doing well; I don’t really have a strong perception of myself as an atomic bomb survivor.” You can see that in her expression. When we took the second picture about 30 years later (in 2005), she requested that I shoot her at work again.

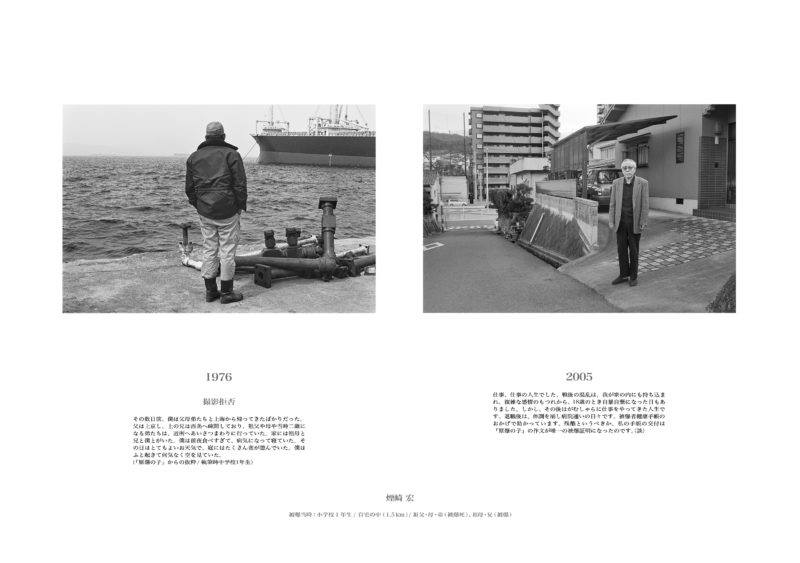

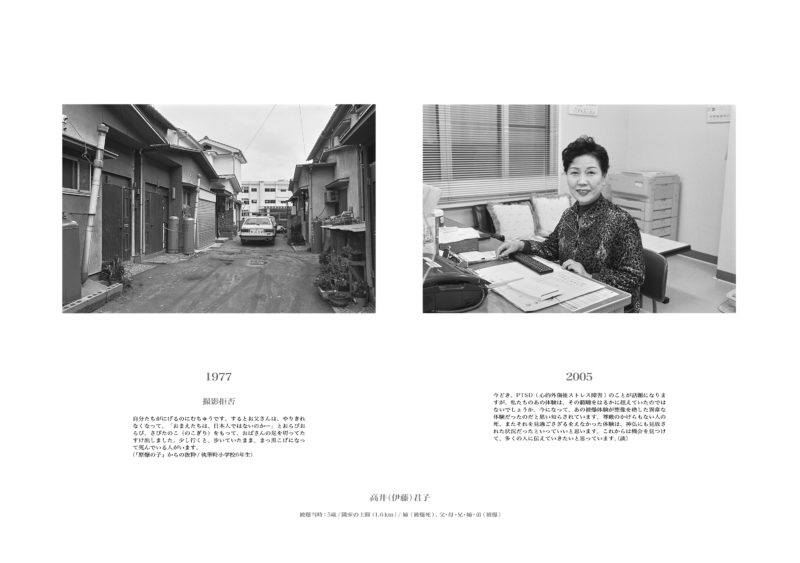

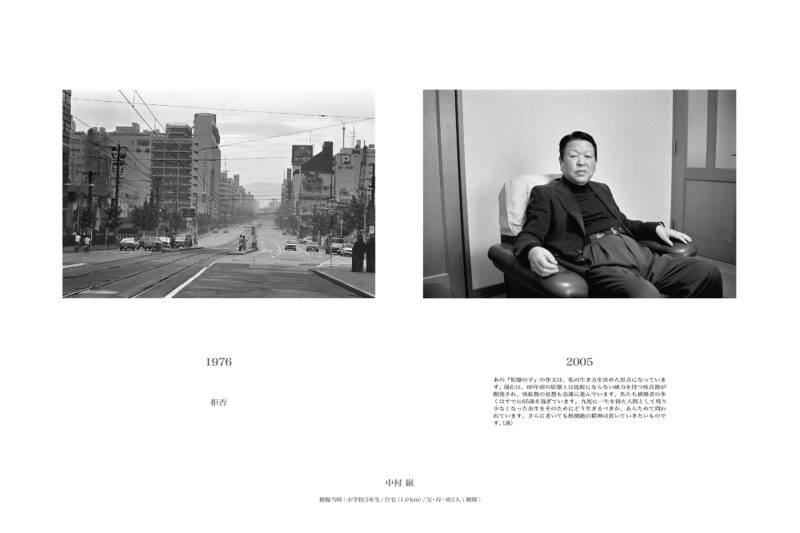

Many people I worked with, not just Hayashi-san, wanted to be depicted in their backyards or workplaces. There were many different variations of their requests, but they were these sorts of everyday depictions as opposed to dramatic portrayals. It was something that conveyed the ordinariness of their families and daily lives, as this is what they valued. This was a way to express that these survivors are living ordinary lives the same as us. Within these everyday environments, there were variations because the project started with 107 people. Within that, some had passed, some refused photos, and some said, “You can photograph me, but just from the back.”

But I didn’t want these to be simple family photos. For that purpose, I added text. In most cases, the text was their own words from when they were a child, first or second grade in elementary school. At the time, they had kept atomic bomb survivor experience diaries. Without this text, you might look at the image and think, “Oh, okay, it’s just her dancing, and this is a photo of her hobby.” But I thought it was important to write about the experience of what she had gone through. So especially for the Hiroshima 1945-1979 series, I didn’t want it to be the people alone but the images plus text. By adding these messages from the past to the images, those viewing the photos realize for the first time that even though these people are leading everyday lives, they are survivors of a cruel experience who have made it this far.

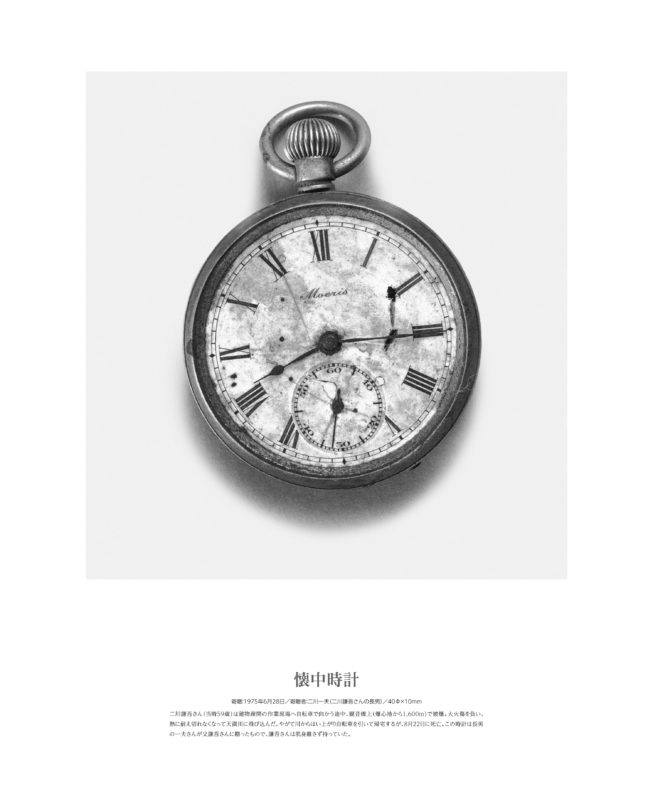

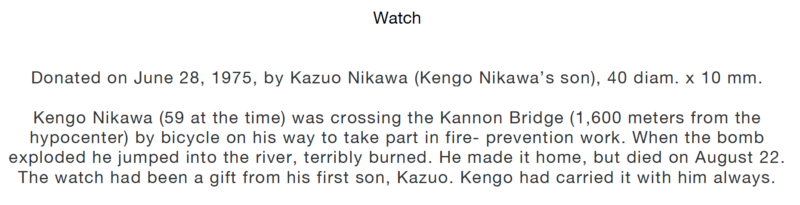

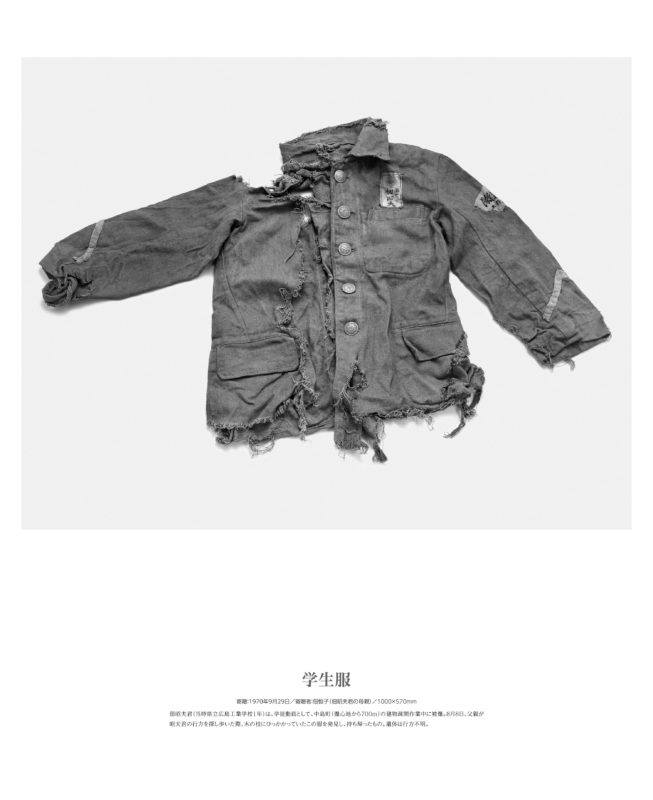

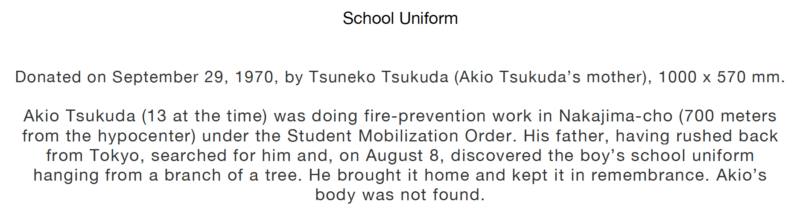

You also use text in Hiroshima Collection, describing the experience of the object and its owner at the time of the blast in 1945. Using the text to bridge the past and present in your work, I was wondering how you strategize achieving balance, both between past and present and between text and image.

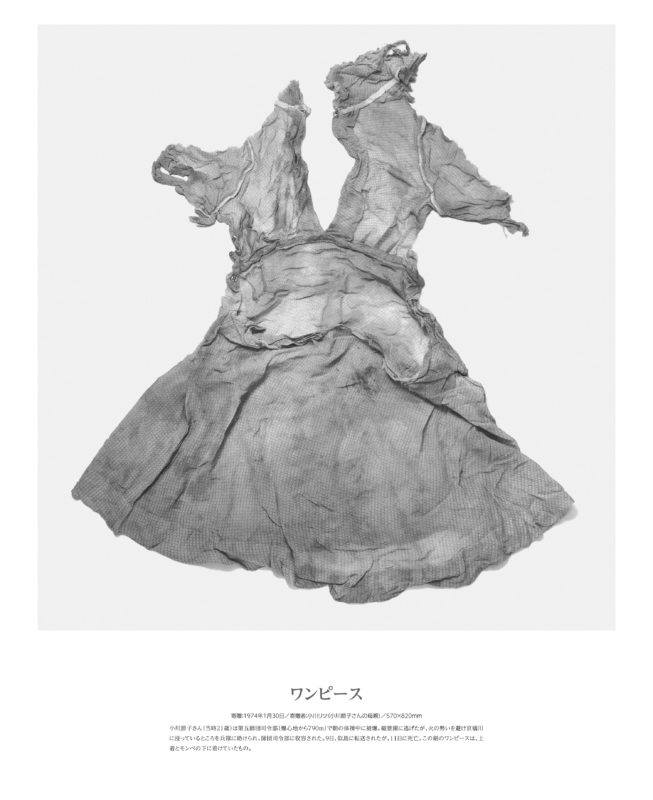

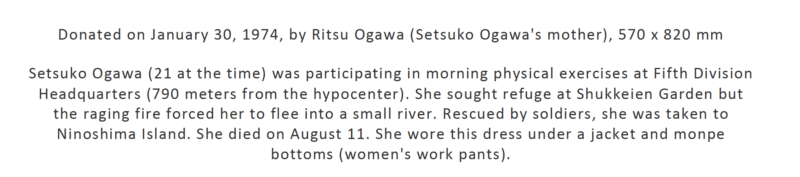

In terms of photographing the atomic bomb artifacts, these objects express this cruel experience through tangible markers like burns or scars. But with these objects, I wasn’t looking to depict them dramatically. Take the image Dress (1982), the importance was its symbolism. The viewer looking at the photo could have a realization via an association with their own dresses.

For most of the things I shot, no matter what country the viewer is from, they’re going to be able to relate to these items because they’re things that exist at the same level within their daily lives. There is this symbolism in this. To bring out the common characteristics of these items, it’s not a matter of depicting them as simply as possible or showing their destruction for the purpose of empathy. It’s about the symbolism of ordinariness, of what happens when the everyday abruptly stops.

There’s explanatory text along with the artifacts at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, so I wanted to use the narratives contained within them as succinctly and straightforwardly as possible. Some stories ended in death, and there were many different variations of these narratives, but my premise in taking these photos was that the text would be on par with them. The text would be on the same level and put in the same space as the images.

I hoped that having the text on the bottom while viewing the photos would cause viewers to develop an interactive relationship where they would read the text at the bottom and then look back up at the image and vice versa. As a medium, photography needs to be superior to words; complementing language is not enough for it. There was the idea of the aesthetics of the photography accomplishing this, but this is something I strongly oppose. When trying to capture this phenomenon that happened over 50 years ago, text can express the past, but it is not clear in photos. So to clearly express the past, I purposely and unreservedly create a single image with the photo and text on par with each other.

Additionally, in most cases, I felt that I had to shoot the items from the deceased in a beautiful way. They are tragic, but the photographer should not unilaterally portray them dramatically or tragically. The more beautiful the images are, the more power they have to draw people in.

Photographs from the Hiroshima Collection are currently being shown in the 58th Carnegie International, Is it morning for you yet? Do these photographs and their subject matter have a different meaning or impact in the United States, the country that launched the atomic bomb in 1945?

Regarding the exhibition, it wasn’t me who chose which works would be exhibited, it was the curator at the Carnegie International, Sohrab Mohebbi, and the associate curator, Ryan Inouye. So I was quite surprised. My personal intention was not that I wanted America to see these images. I wanted everyone in the world to see them, and of course, this includes America. I thought it could be very dangerous to show these images in the U.S. I would like to praise his bravery. I think he had a very strong spirit as an American to be able to choose these images and show them in the U.S., as the basic concept is questioning one’s own country’s political policies up until that point. Perhaps it’s America’s culture, its young culture, which allows for this bold questioning. It is said that Japan has a 2000-year history. The U.S. might only be one-tenth of that, but its young ideas and dynamic choices are wonderful. Privately I worried there might be some pushback or complaints that would emerge and damage their bravery, but during my brief three-day stay in Pittsburgh, many average citizens related to it, saying, “This kind of thing could also happen to us.”

Experiencing this shared sentiment in that space was amazing. I don’t know if their receptivity came from the fact that this happened so long ago or because of the current situation with war in Ukraine. Perhaps it was good that my photos were not expressions of hatred. I think that there are many reasons why, but I’m extremely appreciative of those behind the exhibition and the general public who put aside any aversion to come see it.