Jurrell Lewis – Some of the materials you use are very specific to Fall River, where you live. Could you talk about the way you use these materials, and the relationship between your work and Fall River?

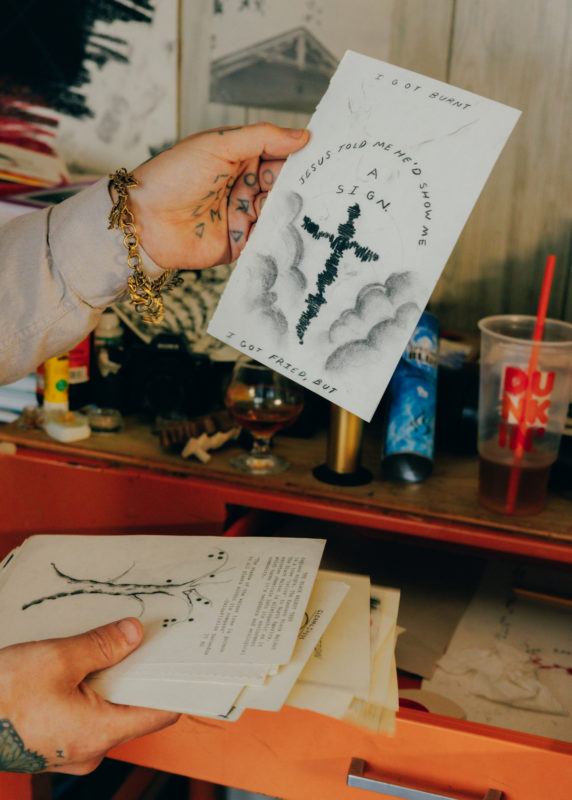

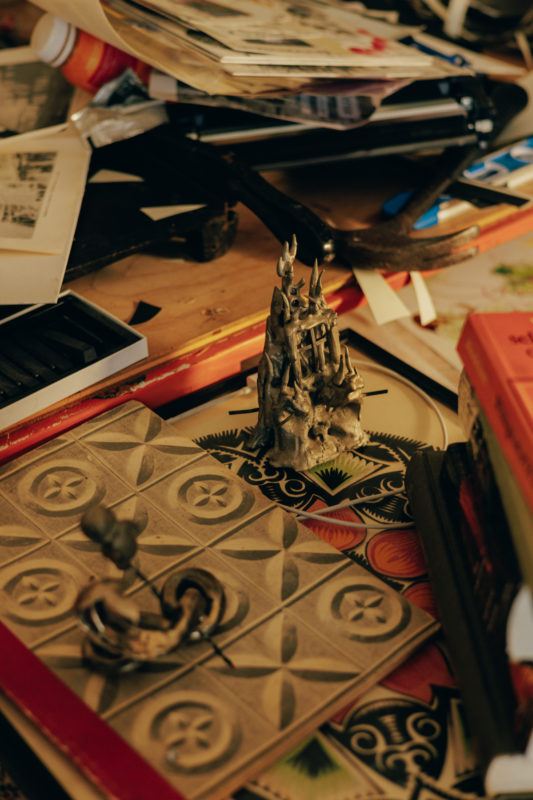

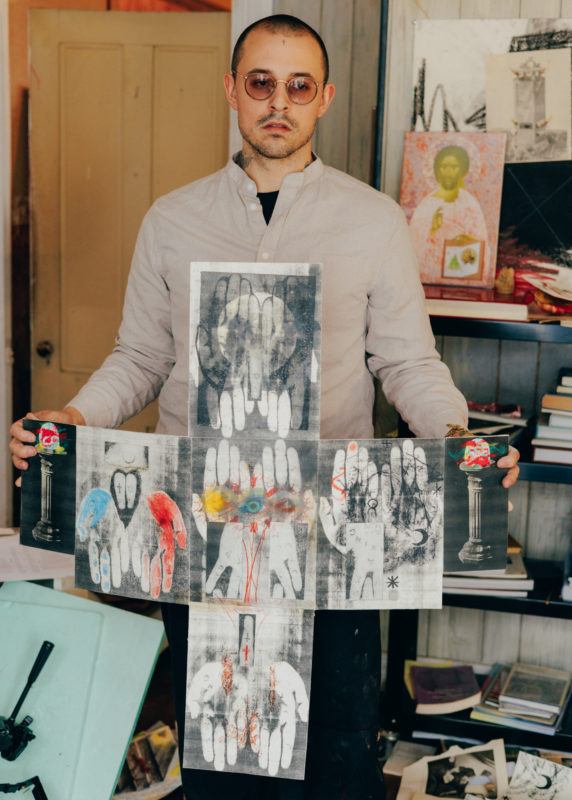

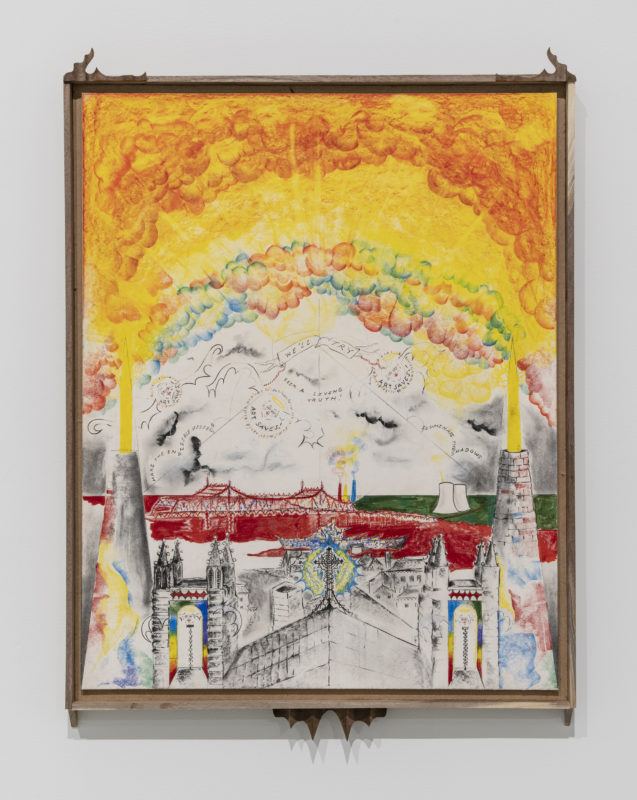

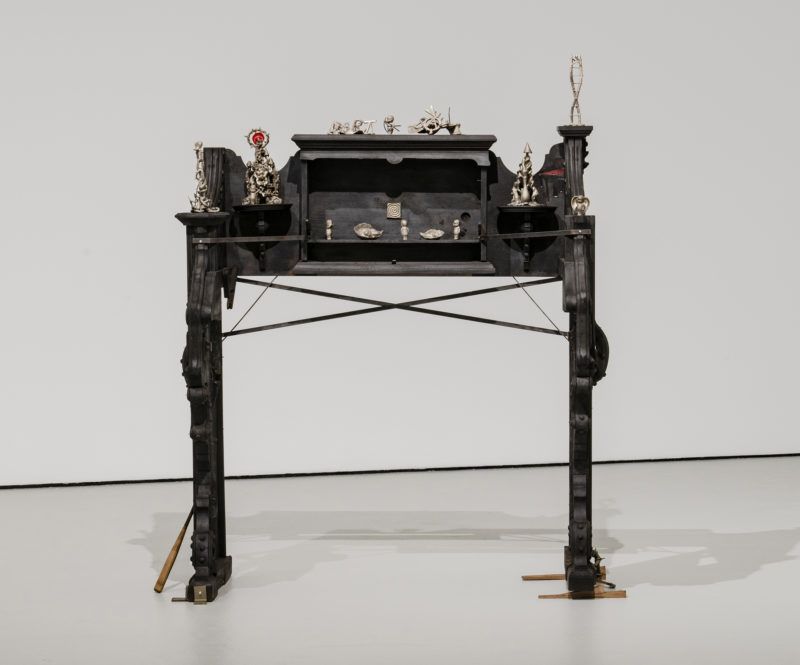

Harry Gould Harvey IV – I try to render truths in drawings and carve frames from wood forged from these lands and these properties in Fall River. Some of these are properties of old Victorian wealth, where I take the chainsaw from the back of my Cadillac and I just limb some off for myself. Some of them are the old growth forests where a limb fell down naturally, died by fungus infection, or was taken by lightning.

If we open our eyes wide enough, we can see that every single molding in every single building was labored by someone’s hands. It came from a tree that came from this earth. Next time you grab the handle of a door, you should think about the 18 pieces of wood that are in there and the craftsperson that put it together. My works are proxies for people to hold conversation when my body’s not there.

The time we spend together, that’s really the beauty of life, so how do I advocate for that?

I sell objects and then spend time at the Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art (FRMoCA), which I co-founded with my wife and partner in FRMoCA Brittni Ann Harvey, because that’s really where I get my fruit and reward, with young individuals. I think a lot about holistic care, ecology, and communalism. I try to stay focused on ecology and what that means for the community that I’m from, what ecology actually relates to in terms of the air we breathe, the water we drink, as well as the sociopolitical infrastructure and the violence that’s inflicted on working people.

It sounds like ecology is central to your practice, thinking about the many ways we relate to each other, other organisms, and our environment. You’re currently working on a project that addresses local ecologies directly, right?

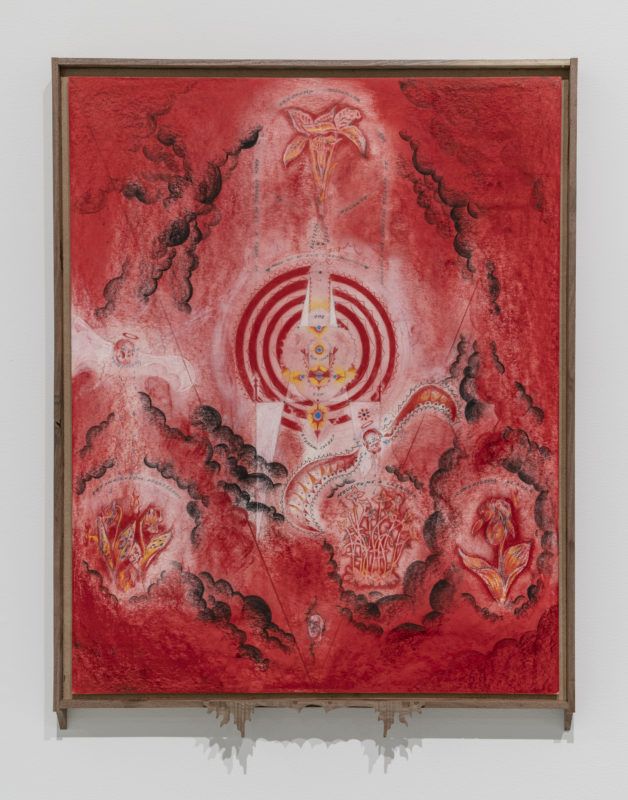

Yeah, for this project I’ve been in conversation with Jen Mergel, a Boston based curator, and I have spent a lot of time at North Park in Fall River, which is a park built at the later end of Frederick Law Olmsted’s life. I started to think about how we could look at the ecological structures that are here at North Park. What artistic phenomenon we could derive from them, and what proposals we could put together that may make an ecological impact. And how could the proposals be integrated with programming at FRMoCA. Like planting Lobelia Cardinalis (Cardinal Flower) to try to get the Ruby Throated Hummingbird back in visible happenstance all throughout the city of Fall River.

In North Park we have a wading pond and it’s full of thickets and Autumn Olive, an invasive species that’s really bad for the ecosystem. But right in the center there is a huge patch of Red Osier Dogwood, on top of the asphalt with moss as a soil, where there are so many songbirds.

How can we bring attention to this ecosystem without destroying it, or denying how it became this way? Denying why it’s in disrepair? Or ignoring the reasons why this plant has to be so pioneering? It’s growing on top of asphalt and using the partnership of a club moss because it’s more efficient than soil. That’s a really unique, collaborative relationship. If any ‘improvements’ were to be made to the wading pond you’d be destroying one of the most delicately balanced native structures that remains in Fall River, in order to do some type of beautification to it.

I hope to work with Olmsted Now and create a written understanding of ways that art and planting paradigms could interact with Olmstead landscapes and try to get some of these projects ready, to bring in different native cultivars. I want to then record, in a somewhat scientific but still poetic manner, what phenomenon might happen? Do uglier, swamp flowers bring more bugs? Whether the ornamental, prettier milkweeds bring more butterflies or if it’s the swamp milkweeds that end up bringing the most monarchs? Then, what we can do is figure out how to be further ecologically responsible in terms of replanting the parks from there.

People and community are also a part of the ecologies you’re working to understand and better, how are you working to address them?

That’s really been my main focus lately. I just felt so inclined to start FRMoCA with my partner Brittni right at the beginning of the pandemic. It was a Hail Mary, creating a working model of how an arts institution could serve its host community in a way that wasn’t bureaucratic or discriminatory. With FRMoCA it’s not our main interest to optically shift the perception of Fall River or beautify it. We’re trying to directly allocate some resources to students and the community. For that, we need a living, breathing body that has a lot of connections, with different people who are willing to take the time to understand how stark reality can be here in Fall River and in any other post industrial city, across the United States. Cities that have been affected by globalization, but largely unaffected by the benefits and progress of it.

We started FRMoCA during the pandemic through a collaboration connecting the contemporary art world with the Azorean diaspora in the Azores and Fall River, with funding from the Fabric Arts Festival. We thought we would be able to do something that could have some sustainability in the city of Fall River. Within a couple weeks, another laborer and I built out about an 8,000 square foot space on the ground floor of an active textile mill, which is the first front gallery of FRMoCA. We built the best example of a white cube that we could provide with the limited resources and timeframe we had.

The majority of the money went exclusively to sheetrock, two-by-fours, paint, and stuff like that. We came up with the name, the Fall River Museum of Contemporary Art and had our first exhibition called Group Exhibition Number One. We thought, “Well, if we do number one, then people might assume there’s gonna be more. If we call it the Museum of Contemporary Art, then what does that mean when you shut one of those down?” Since then we’ve had a couple group shows, we had a class from the University of Massachusetts come and we let them take the space over. We gave them the tools to do it all themselves and they had to deal with everything in that exhibition. We’re doing linguistic exercises with students, and having them spray paint on the walls and learn to dry vegetables with artists. It’s really been an incredible collaboration.

It has been kind of an experiment in how we can really use language, the history of musicological terms and conventions to begin to subvert and inspect what it is a museum does in a community.