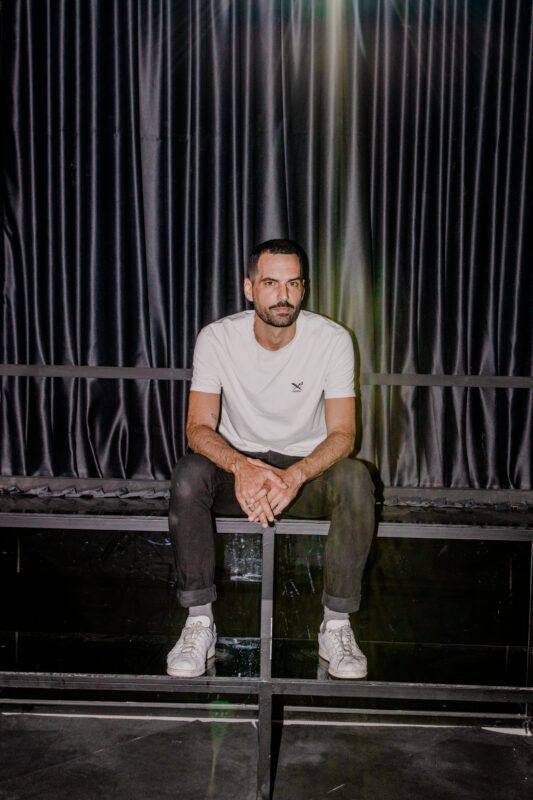

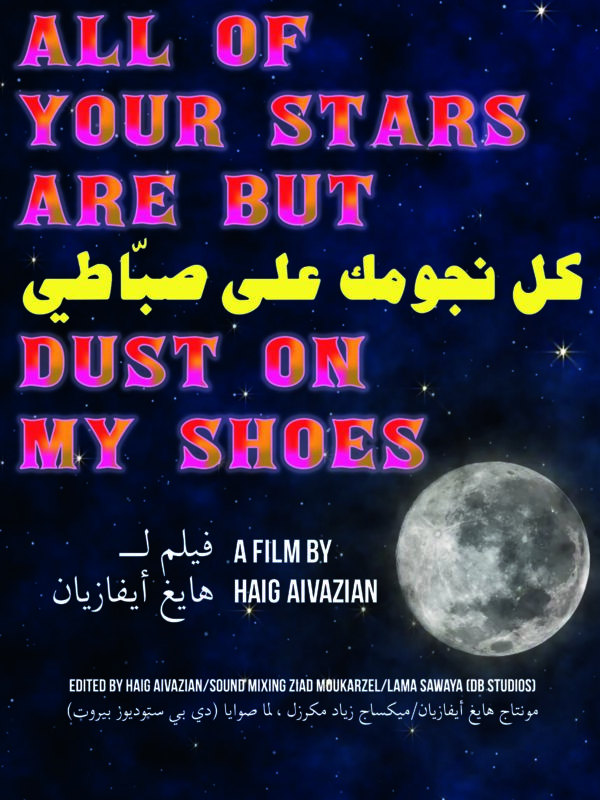

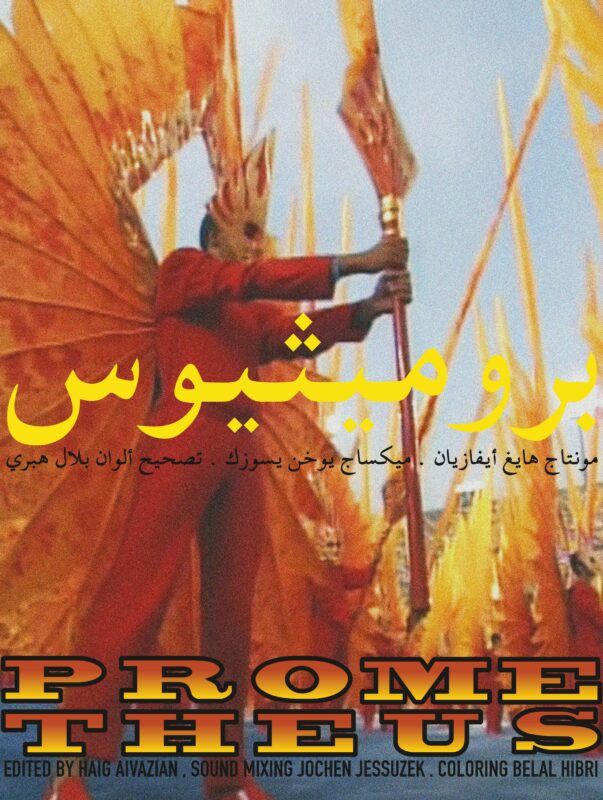

May Makki – Prometheus (2019), All of your Stars Are But Dust On My Shoes (2021), and You May Own the Lanterns But We Have the Light (2022) are three works that feel rooted to the same source of inquiry, sometimes even referencing each other. Where did these works begin?

Haig Aivazian – They come out of the same body of research, which itself was building on a much older work that I made between 2009 and 2013, titled How Great You Are O Son of the Desert!. I was at a residency in Paris in 2017, and became increasingly interested in the uses of military technology in sports, tracking technology in particular. I was looking at the ways in which technology travels and morphs and transforms both itself and whatever it is being applied to. Mainly I was looking at the post-terrorist attacks in Paris, the Bataclan attacks, which started at the stadium in Paris.

That research resulted in a lecture titled World/AntiWorld, and one chapter of that lecture was about the history of public lighting as the first police tool of mass surveillance. One thread I follow is the movement from the mandatory requirement that each individual carry their own lanterns to light their faces and to identify themselves, to a generalized light, through a public lighting system. And from the onset, this tool creates a strange legal precedent, where early court records show much higher conviction rates and direct correlation between when police reports specified that a crime happened underneath a lantern. But the wider research was looking into sports technology, tracking, identifying, and the collusion of markets, military, and police techniques and technologies. So these three works all come out of that entanglement. And all three of them are still exploring the administration of light and of its withdrawal as tools of control that take on very, very different modes.

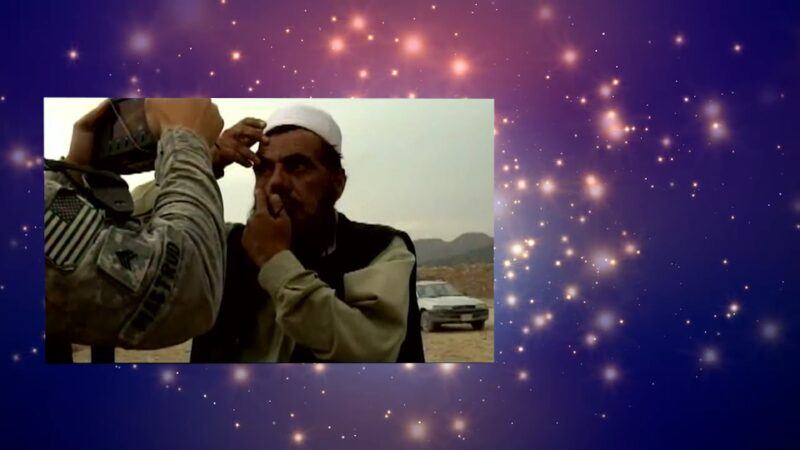

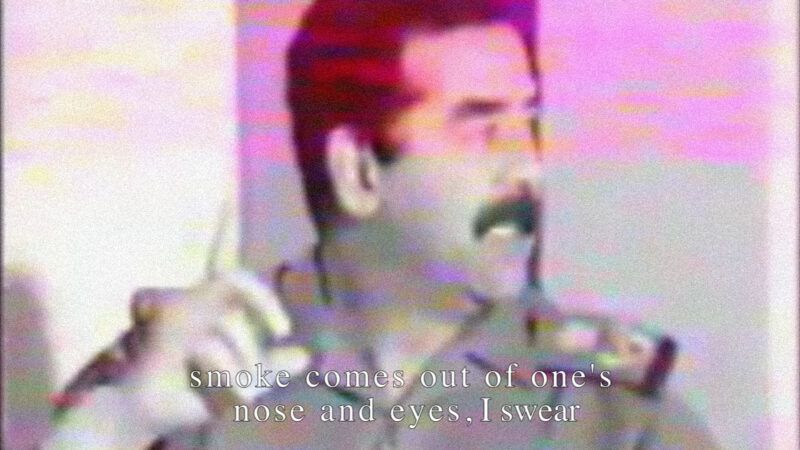

In Prometheus, you compile footage from various sources structured by two primary subjects: the US “Dream Team” of the 1992 Olympics and the Gulf Wars. How did you come to associate them?

I guess just chronological proximity, and having lived those two events as a pre-teen. I remember both as being televisual experiences. In 1989 or 1990, I forget, my family and I had recently moved from Beirut to Sharjah. We were escaping the end of the Civil War in Beirut and landing in the vicinity of another war there. I remember how Operation Desert Storm transformed television. At the time, there was only one English-speaking land channel in Sharjah which began after noon prayers and stopped at midnight or something. And then suddenly the channel started streaming 24-hour CNN news coverage. So there was this kind of regime change in how one watches television, how one watches the news. And later, I realized that the televisualization of that war was a transformation of warfare at large.

On a more embodied level, American ships would dock in Dubai ports, and so there would regularly be groups of Marines that would walk around in the malls. I, and other boys of my age and friends, had very complex feelings towards these Marines. One of admiration as we related to all of these cultural things that we wanted more access to, particularly basketball and hip-hop at the time. And on the other, we associated them with this active aggression, which was in some way affecting our lives. For me, these were two very particular, very inseparable feelings associated with “American-ness.”

Then later, when I started working on Prometheus, I started thinking historically about the post-Soviet moment, both in terms of those Olympics as the first post-Soviet games with all these new countries participating, and then also the supposed dawn of an era of a new singular superpower. It was a moment of American dominance through both soft power and brute force.

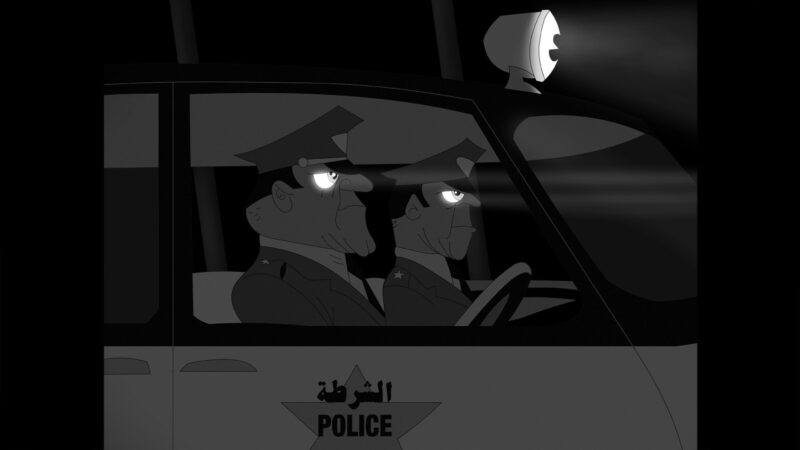

There’s an interest in animation and cartoons throughout your work. In Prometheus and All of Your Stars, cartoons are one source within a wide range of references. However, in You May Own The Lanterns, you move beyond found footage by reanimating the cartoons yourself. What inspired this shift?

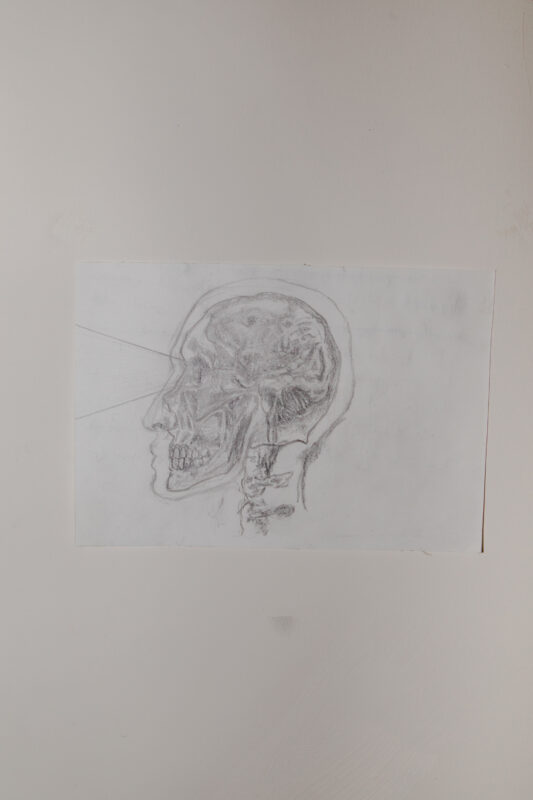

In my practice, generally, drawing has always been formative. For You May Own The Lanterns, I don’t know if I knew I was going to redraw everything from the jump. It was more as I began to construct the film when putting the footage I found from different eras of cartoons on a singular timeline, that I realized, oh, I like this particular scene and this particular composition, I just wish that the person in the scene was holding a martini glass instead of a VHS tape for example. So I approached Chadi Aoun, who did the animation. I would do the reference drawings for the most part, sometimes two or three per scene, and then he would go from those and add and animate.

One of the many things that draws me to animation is that it seems to me a privileged site to explore metamorphosis, and the idea that we would recognize characters despite them transforming all the time was something I was excited to attempt in the edit. None of the characters in the film are stable subjects, other than the oddball narrator. But I worried that the differences would be too jarring and distracting, so the concern from the beginning was to find a balance between the nature of the found footage film and enough unity for the story to flow. The fact that I chose to make it in black and white for example, was as an homage to a film noir aesthetic, but also a unifying element, a kind of envelope that could negotiate the harshness of the cuts.

There are a number of important examples that come to mind of animations and comics coming out of Beirut. Does that context play a role too?

Yes, there’s a tradition of comics and animation in Beirut. It’s quite vibrant. It has been for a long time. There are various collectives, publications, and also festivals. There’s a popular animation festival called Beirut Animated which has been around since 2009. A few months ago, there was a rekindling of sorts, with a gathering of animators for the launch of an online database. But another thing I would say is that it’s very hard for me at this point to refer to that lineage or history and say that, because it existed in the past, it’s still the case today. Because that reality changes all the time. People are leaving Lebanon in droves, all the time. And because it’s a small art scene with all of its different kinds of areas, you feel it in a very big way. So I’m not sure who is left.

Because of this, I find it all the more integral to how I’m trying to think about how to make stuff in this context. Anytime there is energy or enthusiasm, or the will to do stuff, which are such rare resources, anytime there’s a collective of some sort that’s invested in an object, and trying to figure out an object or practice or whatever it is, I’m interested. And there’s been a few of these in the past years. Comics is one such community, and music is of course another.

So yeah, I’m trying to figure out ways to be in conversation, to be in collaboration with these kinds of collective things. And to see if whatever access I have to mechanisms of the art world can be channeled towards a modest kind of activation of parts of those scenes in some way.

In your essay “Getting our Pants Hemmed (On Poiesis and Praxis),” you describe the issue of language in setting the terms of, let’s say, social and political movements. I’m interested to hear you talk about how this may relate to the development of a visual language in your own work.

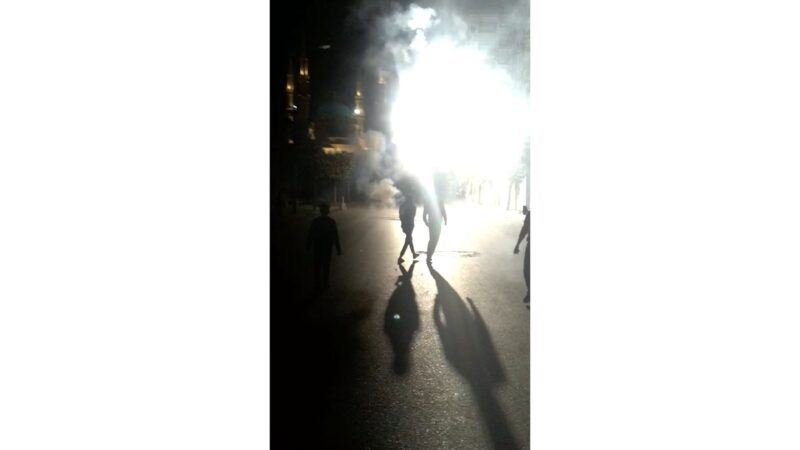

So there’s been just this crazy shit that’s been happening in Beirut in the last three years. I don’t know of any truer way to say it. And there are mobilizations, of course, in response to all of those things, because people don’t have a choice. People who’ve lost loved ones in the explosion three years ago, have seen nothing but meddling from the political class who only acts to protect its own, and to make sure no one is brought to justice.

As I experience it, on the one hand there is the sheer unfathomable scale and madness and an all-encompassing onslaught on any notion of dignified life, and then on the other, a kind of impoverished repertoire of tools. Linguistically in particular, but also organizationally, politically, et cetera. Those things have been taken away from us historically and systemically and have to be reconstructed anew.

But if I just take language and how demands are formulated in public space, often I hear people list out the instances of our dispossession. And I’ll see it on TV, I’ll see it in protests. Anytime somebody puts a microphone to somebody’s face, they address the very culprits and tell them, “You starved us. You stole our money, you exploded our city, …” And its a much longer list. All of those statements, while profoundly true, have so far failed to mobilize. After the buoyancy and creativity of the uprising in 2019, this language has had a hard time prompting people into action on any large scale.

This is in part when I began experimenting with these different modes of associating images in particular ways, and thinking about editing more rhetorically, thinking about punchy cuts and more energetic levels that are more inspired by, I don’t know, sports advertising or music videos or this kind of thing that is maybe not politically as pronounced in this particular way, but that has tools that I think can be put to political use somehow.