David Eardley- You’ve spoken about your connection to objects. This is something that often shrinks as we get older, but for you it seems to have only grown stronger since childhood. Why is this?

Gabriel Rico – I realized the importance of objects 10 or 15 years ago. It’s like when you wake up and you start to really see the power in the material world.

Our way of life is very egocentric. We think we are in the middle of something, which is a very pathetic way to understand the things around us, because you cannot be the center since the other being—it doesn’t matter if it’s a human, or it’s a rabbit, or it’s a dog—thinks the same. So where is the center?

An object, by definition, can be an atom—from that scale to the biggest scale. The universe can be an object composed from another object. In that way, we are an object. We are living in a very objective world and we are a living object, we actually create just a very tiny fraction of the universe. All the other objects outside of the Earth, or even the objects inside the Earth—even the non-human made objects—can still be there or exist there without us.

But matter is a very powerful tool to transmit information. This is where humans start to manipulate matter: to create a dialogue between or a connection between the past and the present and to protect us into the future and contemporary objects have that power. The way you dress, the way you decide which notebook is best for you, or what kind of pen you want to use.

In that way, the objects are just a way to find myself. It’s a very powerful way to project my ideas and project myself into this reality and transmit something without speaking or without talking or without writing.

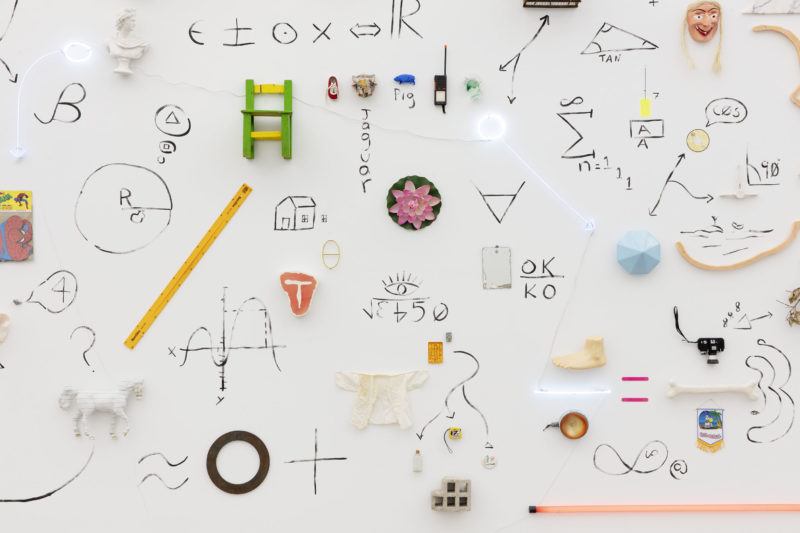

Most of the objects I use have a function before I decide to use them in my equations or in my pieces. But in the way I use the objects, I try to cancel that function and suppose a new way to read the object in the material world. In that way, I can, or the pieces can, create connections between the public and the meaning of the object. It depends, of course, on the past experience of the people or the public who’s in front of the object, but more or less it’s like that. It’s a very tricky topic.

Why is context important in your work?

One of the very interesting things about quantum mechanics is the suggestion that everything is not defined until someone [witnesses] the matter and creates a materialized universe. I think that everyday objects have kind of the same reaction. For example, if you are in Mexico City and you go to a very popular mercado where you can find tacos or fresh fruit, your sense is going to be very excited by the food and the smells and at some point your mouth will start to water, and you’re going to start to think about it—the banana or orange.

It’s because of the context. More than museums, a white cube space has the power to contextualize the meaning of objects and that’s very powerful because the red inside the white cube is more red than the red in the market. It’s just appearance—it’s not less red, but the power of the white cube needs to be investigated because, more or less, it’s like when Neo in The Matrix has access to this crazy place to test waypoints or to test martial arts or wherever. They use white spaces to cancel the context of the objects and, more or less, my work and my process are kind of the same.

I have a very large space in my workshop where I can bring the objects I find in the streets and let them live there for one week or two weeks or a month and see what happens in my perception and in the object, and see if I can recognize the real power of the object or not. It’s a tricky thing because, for most people, an object is just an object. But if you take your time, you can really go deep into philosophy and try to define your perception and your position.

Do you see a binary of contextualization and decontextualization in your work?

Yes—there’s two things that compose one thing. In a way, the decontextualization in my practice happens when I start to produce a new piece. For example, if I go to a flea market and I find a really nice piece of trash and take it with me and come to my studio and I clean it and I just take it and put it in a vitrine for several months or several years, the context is not changed too much. I mean, it’s coming from a flea market to another vitrine. So, if you are very picky about that, it’s more or less the same. Two different vitrines in separate places, but the context is more or less the same.

My studio is full of the objects I just collect from all around. So it looks like a flea market. But the contextualization happens when I start to work on a new piece and I decide to use that specific object. When I start that process, I suggest and learn a new way to interpret the object, like part of another big ecosystem.

In the vitrine, the most important thing is the vitrine, but in a piece of art, the most important things are the objects and the communication between the objects that suggests a way to interpret the work.

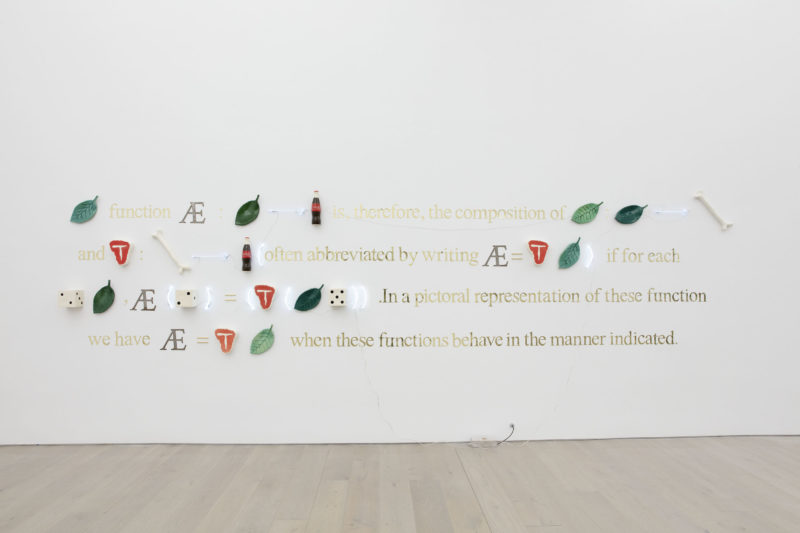

For example, in the past four years I have worked on a series where I use algebraic equations and switch the letters for objects. It’s very easy, in a way, because I explain to the public that it’s an algebraic equation and they start to read the piece from the left to right.

But if I create something more chaotic, the order and the way you can read the piece is lost. You can start from this corner or that corner or whatever. This is a powerful example of the contextualization and the decontextualization in my practice. The way you can read my art is because I spend time thinking about that specific position and that specific order for the objects.