Sampson Ohringer—I’ve heard you discuss your work as a “ceremonial way of living.” I’m curious about the relationship between your practices as an educator, a historian, and a political activist and your art-making. Your work asks art to be more involved in the world.

G. Peter Jemison—I have responsibilities within my community which I have learned and been taught over time. I use the term “cultural worker” because I couldn’t think of how to really define the different roles that I have other than to say: as a human being and a person who is Onödowáʼga, we view our life as a kind of living in a harmony, living in a balance with the natural world and coming to really appreciate it, to really live within it and see ourselves related to it.

Obviously, there are people who don’t think that way. The natural world doesn’t impact their lives. Sadly, they’re being shown the power that the natural world has and that wakes everybody up to the fact that we are not in control. The fact is, the best thing we can do is observe it [the natural world], be prepared, and appreciate it.

SO—You’ve been working on some new landscape paintings while simultaneously questioning what landscape painting means. Representation has been both multifarious and nefarious as it relates to depicting Indigenous people. What does representation mean to you?

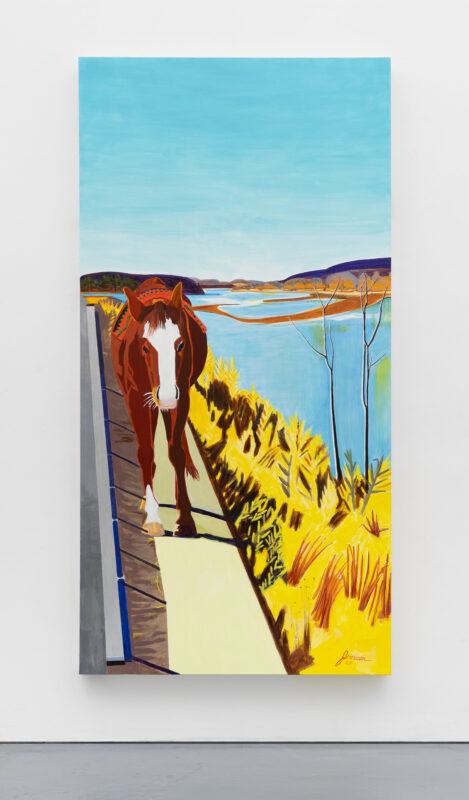

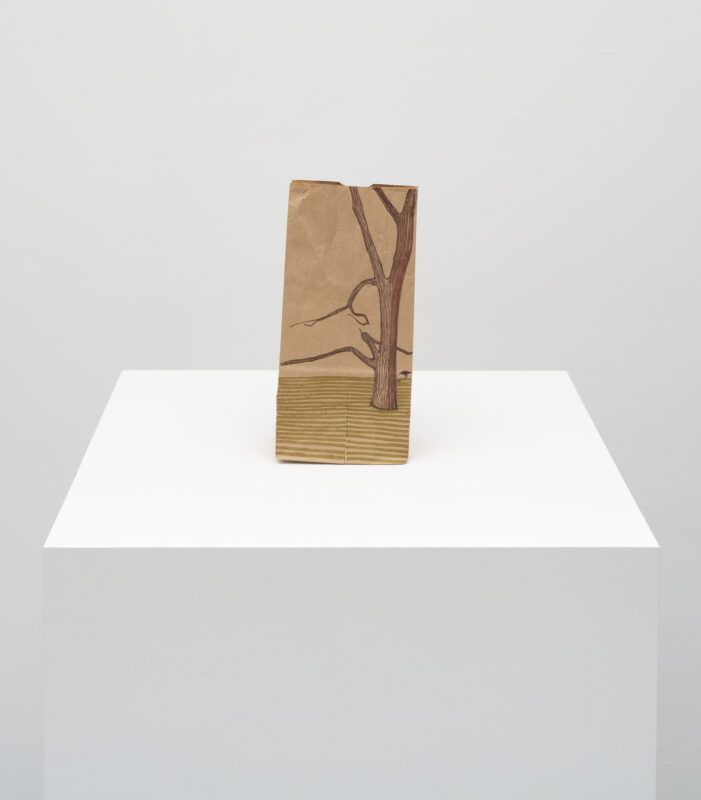

GPJ—I have to identify a landscape that has a meaning to me. Right now, I live in the westernmost part of New York State. In the past, I’ve lived in what we call the Allegany Mountains. Running through this particular territory called Allegheny is a river, and it’s called to us, Ohiyo, which means “Beautiful River.”

That landscape is special to me, I really feel tied to it. Right now it’s part of something that we are contesting. At one point, 10,000 acres of our land were flooded by the Army Corps of Engineers and they condemned it. That landscape has a particular meaning to me and I incorporate it into my painting.

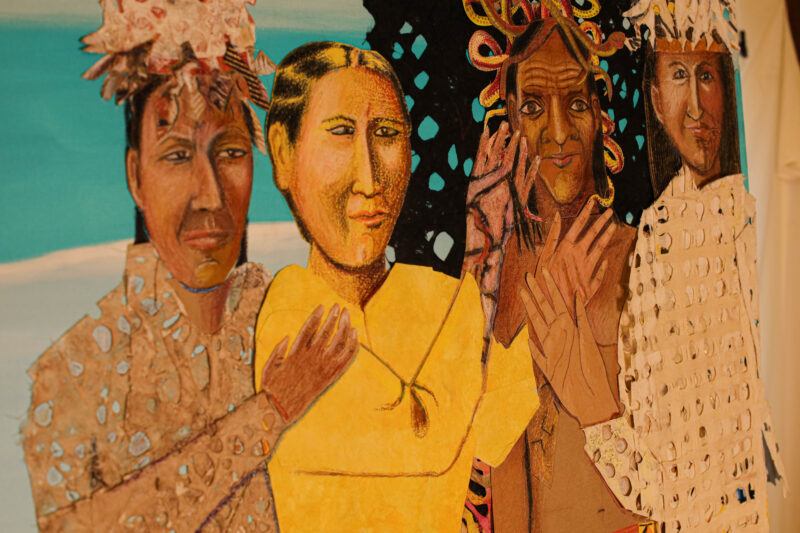

When my parents passed away, they left me shoeboxes of photographs of my family. Looking at the photographs, I want to incorporate them into my work to say, “Whatever your stereotypes are, this is how we really look. This is us.” Mostly, it is me reacquainting myself with my relatives and putting them in the same context together, one that I might not have ever seen them in. I put them together to remind myself of that heritage and who they are.

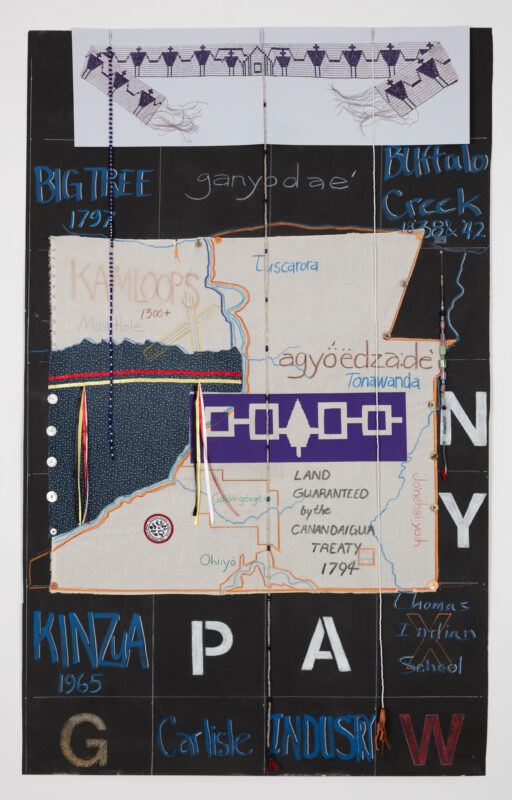

SO—You wrote the introduction to The Treaty of Canandaigua 1794 (a history of the American-Iroquois relationship). And your textile piece, Canandaigua Treaty 1794 Land Guaranteed (2021) was featured in MoMA PS1s’ Greater New York 2021. Your historical investment takes many forms—painting, film, lectures. How do you determine what form provides the best medium?

GPJ—Well, it’s been different things at different times. I did a series of five short films. They were very focused on an aspect that I wanted people to experience by using my own people as actors, developing a storyline, and then taking advantage of the bark longhouse and the landscape to place the story. For these particular stories, I thought film worked best. When I want to talk about the treaty, I have a feeling that my paintings probably explain what I think just as well as maybe a film might.

There’s this other thought and I want to talk about it for a minute, it’s a little bit off topic, but not a lot. What is the point of art? What is the purpose of art? My thinking isn’t just that I want you to see the painting in front of you, but that when you walk away from it, you experience the rest of the world just a bit cleaner or sharper than you did beforehand. You notice things that you hadn’t noticed before, suddenly you catch the beauty in something because that painting brought your mind into a purer focus.

If it does that, it helps you to see. That is the purpose of art.

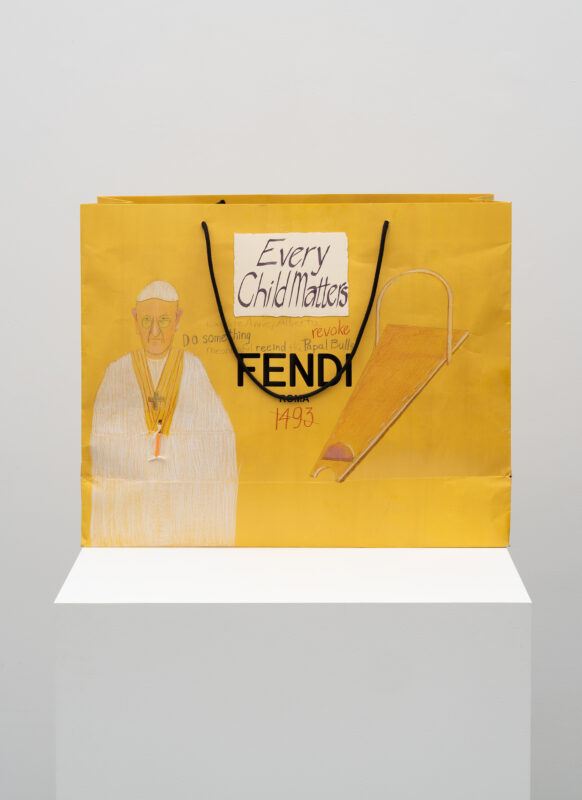

SO—You frequently use found materials such as brown paper bags and treaty cloth. Obviously, that tradition helped define Western art history in the 20th century. But is that a helpful reference for your work?

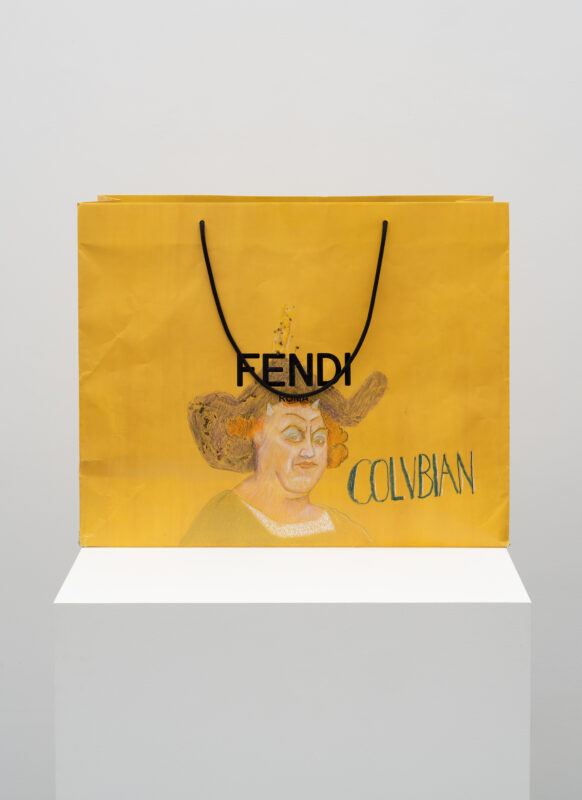

GPJ—Well, the bag pieces began with simply recognizing that it [the paper bag] was a common object, an object that many of us carried. Whether we knew it or not, it was a way that we were sort of united by the fact that we had carried a bag.

People save bags for me. I buy bags if I think I need to find designer bags or I save the bags that I get from shopping places and wait for an idea to come.

I’m using them for a political statement. To begin with, it’s a disposable object. It’s an object that people don’t think too much about. People like the designer ones but then to put something else on them and make that the subject of the bag, it just adds another layer.

The very first ones I showed were at the Times Square show in 1980. During that time, there was a lot of street art, and people were taking non-art materials and putting them together in a way that was art.

I’ve created a Clarence Thomas bag, a Joe Biden bag, a Vladimir Putin bag, just the other people that come and go on the television. What is the icon that you see in your mind from watching or hearing these people over and over and over again? And how do you explain that? How do you create it visually?

I did two Buffalo bags about those horrible killings in a Tops supermarket in Buffalo. I used a Tops bag to create a statement about that. Then I used a couple of very “chi-chi” designer bags to talk about ending hate. The designer stuff is directed at a specific population and the bags are trying to produce desire at these ridiculous prices. To take something that really was a terrible tragedy for a community and place it on bags, there’s an edge there that I want people to sense.

SO—Hearing you talk about what you see on TV and the way tragedy is publicized and depicted, as in Buffalo—these are concerns with mass media, representation, and the role of art itself. There is a very pop and post-conceptual core to that. Are those movements you are in conversation with?

GPJ—So there’s a whole bunch of work from the late 1960s and early 1970s that I actually haven’t shown in much of a public way. One series was created in San Francisco and is almost minimalist—really looking at found objects and ready-mades, but producing rubbings from these found objects to create drawings basically.

After my first stay in New York from 1967 to 1968, my work was very mathematically oriented. I did an exhibit at the University of Buffalo using sheets of foam rubber that were attached to full plywood sheets, then allowing the tension that is in a piece of foam rubber when it’s bent to make forms. It’s hard to describe it, I produced a whole series of drawings depicting these home rubber sculptures that I might create. Then the opportunity came and I built the sculptures but, I don’t have photographs of the installation, it was way back in 1969. But what goes around comes around, and right now people are looking back at Minimalism and the work that wasn’t seen fills in a certain gap coming from a place that people would maybe not expect—that a Native American artist was thinking about and creating things around that idea.

SO—Many people are now approaching these ideas which have long had a presence in Native traditions but they are approaching them from a very western-centric place. It’s like taking the long way to get to similar ideas.

GPJ—I was at RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] last week speaking and one of the curators at the school’s museum curated a Navajo blanket exhibition from RISD’s collection. It just brought back to us this tradition of geometry and abstraction on something that was really utilitarian.

The purpose of the blankets was warmth, then they evolved with new dyes and newly available wool. This evolution reinforces what we know about the tradition of geometry and abstraction and simplifying forms that come directly from the natural world—that there was a great deal of influence exerted on European artists who came here looking at Native American art and experiencing it.

SO—That feels very much in conversation with your pursuit—as an artist, educator, and activist—of a richer and more nuanced account of Native American history.

GPJ—One is informed by the other. I’ve been fortunate to have made the decisions I made when I was young. Some people told me that I was making a bad choice to make a point about being Native American, that it was going to stunt my growth, and that I was going to find limited acceptance. Well, I knew that it was important to do. I knew that I could only be honest by being who I was, but I didn’t know what it meant to say “I’m Seneca.”

Later I learned I’m not Seneca, I’m Onödowáʼga. What does that mean? It means that there are a whole series of things that are ours that we have been given, that we understand, that we know and that we live by. So learning what that is, that’s made all the difference in my life.