In the Studio

Francis Alÿs discusses The Nature of the Game in the 2022 Venice Biennale “The Milk of Dreams.”

Art21 – Could you tell me about The Nature of the Game and your work with children’s games that you’re currently presenting at the 2022 Venice Biennale?

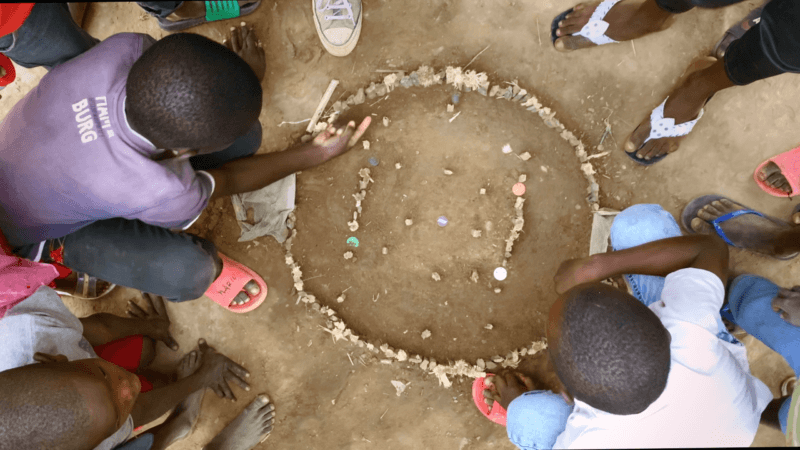

Francis Alÿs – It’s a project that started a long time ago, and in a way, when I first started documenting children’s games, it was more a way of making contact with any location where I was invited to eventually develop more fictional or propositional projects. I realized it was a very rapid way of assimilating to the local codes, the cultural codes, but also in relation to how people react to the camera. How parents react when you interact with children, et cetera. So, it’s been very convenient as the entry point to developing projects. Over the years, I’ve gotten more engaged in the actual ‘nature of the games,’ if you want, and am trying to build a compilation of games.

I think it has to do with my own story. I have small children, so I’m in contact with that universe on a daily basis. I saw them [children’s games] gradually disappearing from the public space. As I saw that, one of the things that fascinated me with children’s games was how they were transmitted from one generation to another.

There didn’t seem to be any sort of master plan behind passing games from one generation to another, but some of the games I’ve filmed have existed for thousands of years, and even those games are starting to be more difficult to find. Their disappearance is a phenomenon that has happened over the last, I would say, 20 or 30 years. You can see many reasons for this.

The obvious one is the way in which children are more into the solitary confinement of video games, or any kind of social media communication. You could say it’s because of the way in which cars have invaded the cities. And not just cars in movement, the way parked cars occupy public spaces is immense. Ultimately, the main factor is probably the parental attitude in relation to letting kids play in public space. We, I’m saying me because it includes myself, are way more cautious and protective with our children than my parents were.

All these factors somewhat affect the survival of street games. That was a push to become more focused on them, and really, if I look at it, it’s only in the last two years that I’ve really focused on children’s games. By that I mean, I opted for this project [The Nature of the Game] for the Belgian Pavilion and I started being quite productive.

The pandemic gave me an extra year. That was a big element in the making of the project. There was a desire at some point to have all new games. So, in the end, of the 14 games present, 12 of them were produced over the last 18 months. I was interested in getting a sense of a moment, this is now and this is what I’m representing.

I’m curious about the experience of documenting the game depicted in Contagio in relation to The Nature of the Game, specifically the balance of documenting both children’s games as universal forms and as reflections of this specific moment in time during the Covid-19 pandemic.

I think Contagio is a perfect example of how kids assimilate the adult reality around them into playing. I think games are a way for the children to assimilate the adult world and adult society, as their way of mimicking, mocking, but also integrating the social contract. At the end of the day, all they did was give a slight twist to a very known and universal game but, by doing so, they froze it into one particular moment of their existence. Adults tend to process traumatic experiences through speech. Children will do it through play, and I thought this game was a beautiful example of how. To think that children are disconnected is wrong, they’re actually very affected and connected and trying to make sense of what’s happening around them. What was particularly striking about Contagio is that there was a nearly identical game in Hong Kong, which is where I first saw it. It was more than similar, it was nearly exactly the same appropriation by the children as a way of processing a somewhat traumatic moment.

What I first liked about children’s games when I started documenting them was their timeless quality, in the space of the game itself time seems to dilute. It becomes an abstract. The only time factor is in the development of the game itself, if you want. And there’s also the repetition of the game, which creates a very particular relationship and in a way protects the space where the children are completely absorbed in the game. The game we just mentioned is the opposite, because it’s linked to a specific historical event.

If I look back on my own trajectory, this particular project is new to me. I went from creating personal fictions to docu-fictions when I started working with children, because I stepped out as the protagonist in nearly all cases. It’s a gradual shift in terms of my role as an artist, or simply my role as observer. It’s something that I don’t know yet what it is going to lead to. In that sense, the past two years were a bit of a fracture in my personal history, not least because I loved it.

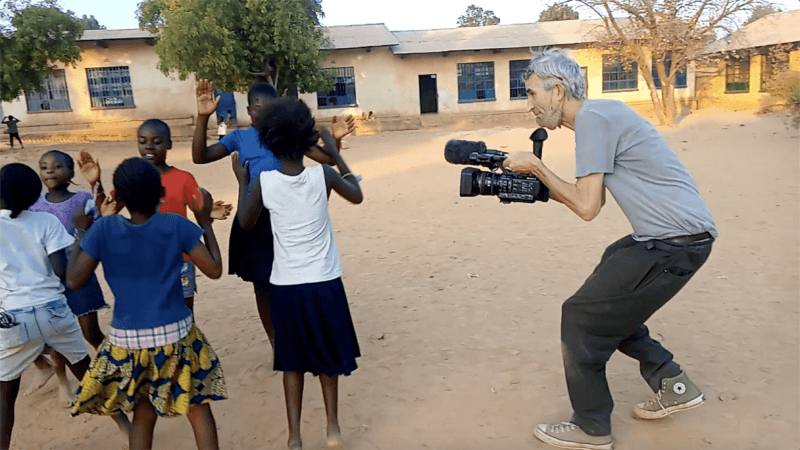

I loved the filming. I loved the surprise element. For as much as you try to grasp the essential rules of the game you’re going to film, you’re constantly trying to figure out: what are they doing, and how do I respond to that? How can I capture it? The contract when I’m filming is simply to gather enough elements so that when I’ll be in the editing room later on, I can offer a version that would make the game understandable to anybody, both in terms of the rules of the game itself, but also in terms of location. Ideally, you don’t need to read anything. You just watch the game and you get an idea of where they are, what they are playing, and what are the mechanics of the game.

It’s a very volatile process because the filming can last anywhere from 30 minutes to an afternoon, and in the best case scenario, I have a second chance the day after, but that’s rare. Most often it’s anywhere between one to three hours, with all the incidental factors that can affect the filming. It’s really entering their world, becoming one of them, and trying to capture the ongoing games, but also the relation between the different children, and how that affects the game, and the society around, which inevitably gathers.

In the case of, for example, Rubi in the Congo. When I started, there were five people around. When I finished, there were 150. And by then, that’s it. With the ambience then, it’s such a distraction for the children, that it becomes something else. It becomes an enactment for them. It’s not a game anymore. All that is extremely challenging.

I’m thinking about Step on a Crack, filmed in Hong Kong, and the experience of moving through space with the young girl and all of the spectators. What was that filming like?

I had seen the game in Japan earlier, so I knew it existed in that part of the world, and that was confirmed by my friends in Hong Kong. We’re talking about October 2020 so it’s early on the pandemic. The city was relatively quiet. It wasn’t deserted, but the activity in general was probably down to 40% of its normal activity, and that’s partly what made me think that it was the right moment to film that particular game, in terms of risk factor. At the end of the day, it’s a child slightly distracted.

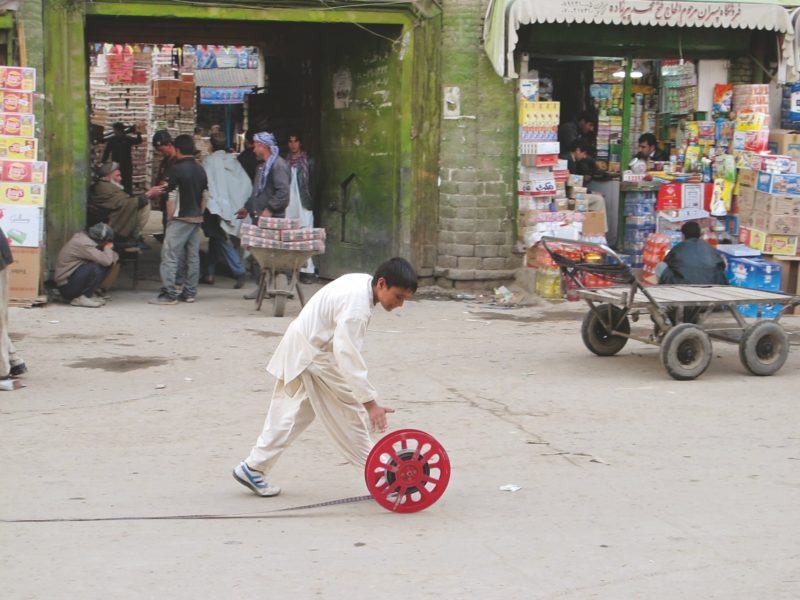

My desire was to portray the city going through the pandemic. The film I had in mind when I did Step on a Crack was probably Reel-Unreel, which is this docu-film where we see the city [Kabul, Afghanistan] through these two children chasing one another: one unwinding reel of film, the other one rewinding. It was more pretext to show what was happening in the background. I think Step on a Crack is similar in that sense. The action itself was a pretext so that people would look at the city behind, and the life of the city, in this case, at a particular moment of its history, but it was a way of creating ambulation, a journey, through a place, and to portrait it, but without making it the first protagonist.

This was the intention. It turned out that the girl was quite charismatic, and she takes a lot of presence and that, in many ways, is the way I work. No matter where, documenting a children’s game or elaborating a more fictional scenario, I set up a situation, and I’m relatively precise about how to set a situation, but from there on the way it develops is out of my control. I’m curious to see what it is going to lead to, and that’s the nature of the game, for myself and for the children.

Interview conducted by Jurrell Lewis in June 2022 over Zoom. Photography courtesy the artist, and David Zwirner gallery. Published July 2022.