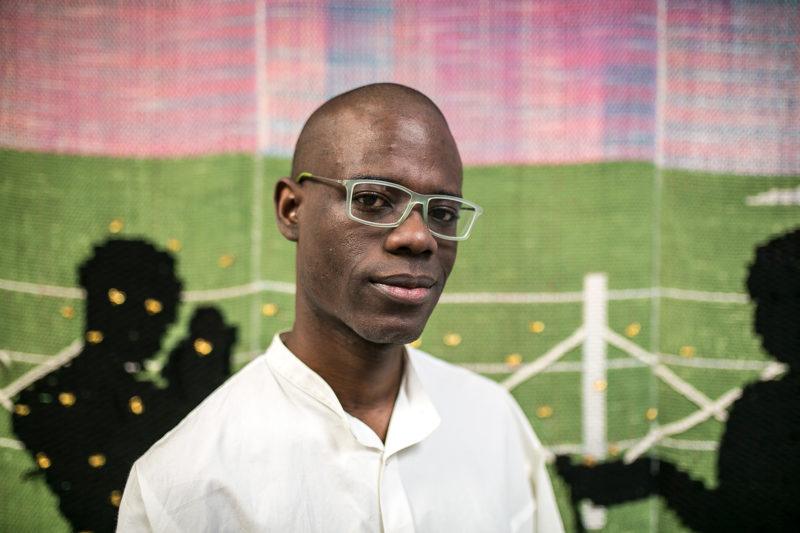

In the Studio

Diedrick Brackens weaves love, labor, and African American legacy into his textiles.

Essence HardenI wanted you to begin with walking us through the earlier stages of your decision to come to weaving and textile works.

Diedrick BrackensI found weaving by accident. I was making work intuitively in undergrad in an intro to sculpture class, using a lot of fabric and string. I had a professor, Mary Becker, who said, “Oh, you need to take a weaving class.”

That summer I enrolled in the only class they were offering in fiber was weaving, and went every day for four or five hours, and immediately thought, “Oh. This is my thing.” I fell in love with the process of it all, how meditative it was, and thought the materials and the machines were so beautiful.

I was so in love with how rigid it was, and how, if you followed the rules, you’d end up with a piece of fabric.

Rules, hard work, pays off.

Yes. It’s so satisfying. I think the challenge that I did not realize until later was yes, you can make a piece of fabric if you invest this much time, but turning the fabric into an object—that I wrestled with for years.

Take us through the process of building a piece. Where do you begin on the loom? How is each piece layered and structured?

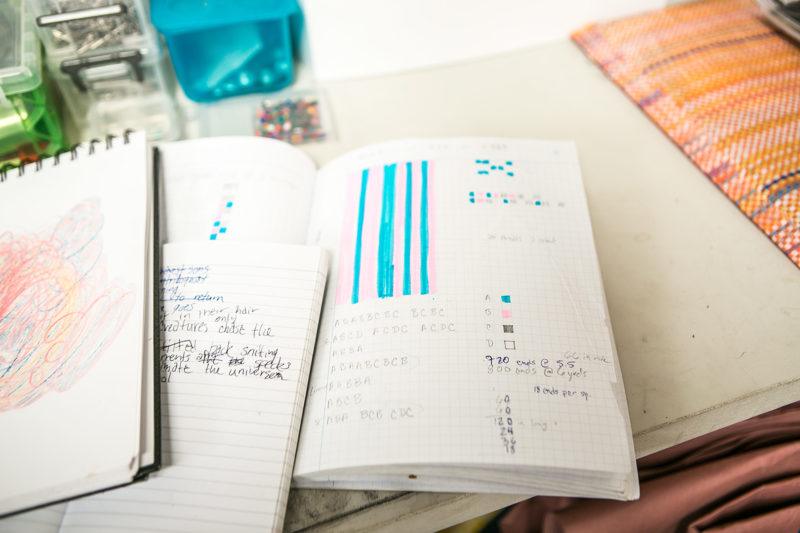

I would say it’s two tracks. There’s the research, writing, and ultimately a drawing, but then there’s also the math. Once I decide what I’m making I have to figure out the dimensions of it and what that means for the overall length of the warp, the amount of weft material. So, the vertical and horizontal threads that need to be dyed. That comes up with these numbers that get interpreted into thread. Sometimes, the concreteness of what I have to do to get the yarns will dictate the imagery, because I know it has to fit within these bounds, then I will make a decision to do a certain gesture.

Cotton is key and/or king to your work. Can you take us through the decision and the import of cotton to you? Buried in that question is my interest in cotton’s relationship to American, new world history and geography, and, how the material can form the practice itself?

The material I learned to weave with is cotton, and it’s primarily based on the fact that cotton is a cheap material and it takes dye really well. It doesn’t shrink as much as other materials do, so it’s predictable. When you’re learning, it’s so versatile. Those were some of the original things that I loved about it.

Take us through a little of your own family history. You’re from Texas.

My family is from Central Texas. Where my grandmother and my family on both sides live, there’s a lot of cotton production that still happens there to this day. Driving home, you go through cottonfields. As a child I remember stories of relatives my grandmother’s age and older talking about actually picking cotton growing up, which was at the time just a story.

As I got older, I was just like, “What? You picked cotton as a child?” And talking about the process, very matter of fact. Being an undergrad in academia, and hearing conversations around race in America and debating it, it was shattering to think about knowing something from a historical perspective, but then having to face somebody who’s telling you this story, was another thing altogether.

Yeah, it’s not so far away.

There was this thing for me, like, “Oh. This is my material.” I have ownership of it. I get to use it to tell stories. I get to try, in some small psychic way, to offer this up as a way to think about laboring over this material in a completely different way for a different end. There’s something great about being so close to this material in this less charged way. That’s the complicated math, emotional math.

There’s a lot of bold, bright colors, really deep hues and this play between synthetic and organic materials. What role does color and place play in your work?

I love color. Before I start anything, I think about what ways I can use color to strike the mood that I want works to have. If I’m operating in a practice that is so much about the material, then can the water be also considered as materially important? Does it impart something that could not otherwise be achieved without the Mississippi, or water from the lake in my hometown or these things?

I’ve been using those waters as carriers for the synthetic dyes that I’m working with, but only using black dye because it theoretically has the full spectrum of color. The ways black shows up when it’s altered even slightly by the temperature and salt content present in that body of water feels important to think about relative to other ways that water shapes most folks’ experiences. I would argue, historically and in contemporary life, Black folks’ experiences are shaped by water. Thinking about access to water and clean water, climate change I feel is affecting Black folks in major ways, and on, and on.

Synthetic materials, the dye you’re using, and in tandem with cotton, all these little gestures and suggestions pop up.

Sometimes that synthetic thing is just the right color. I think there’s something about using a strict palette, for instance, of materials that feels that it could trade in some level of elitism, that then the material becomes precious. It’s all cotton, it’s 100% cotton.

I think folks from a craft background can be very guilty of fetishizing—it’s pine, it’s mahogany, it’s silk—that I’m like, “It’s acrylic yarn. I got it for $5.” I want to elevate all of these material languages because I think, again, it folds back into thinking about the history of quilting for African Americans. You take the scraps and all the things, and then it becomes precious through your labor and love of it. I feel like this is the underlying ethos that I try to keep up in the works.