In the Studio

Cecilia Vicuña taps into instincts to imagine solutions for the impossible.

Art21There’s such a variance in the scale that you work at—from the miniature precarios to the enormous quipus. How do you think about scale in your work?

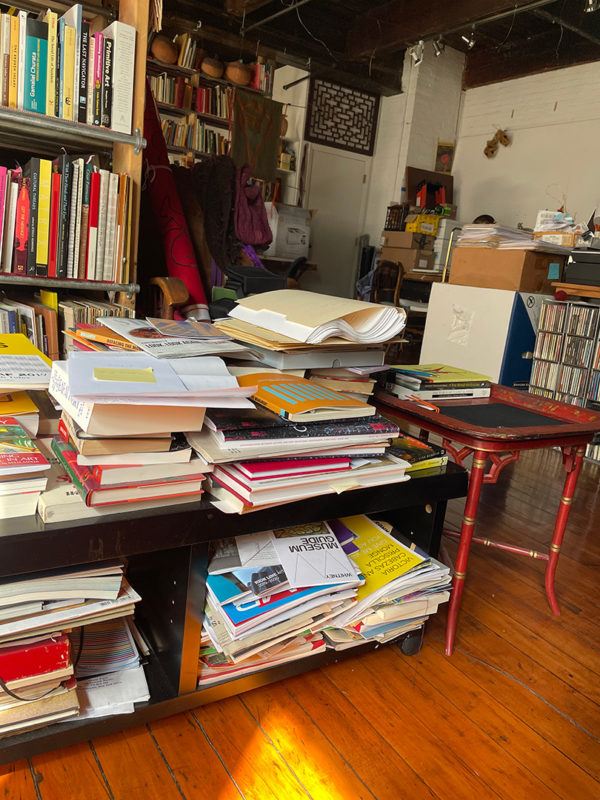

Cecilia VicuñaI think I belong inside an ancient culture that has continued within contemporary culture. When I was maybe three or four years old, I was knitting miniature sweaters. As I became older, I encountered archeological museums and found that this kind of miniature has been part of the ancient Americas for thousands of years. Was I thinking about that when I was three or four years old? No, I was just doing it. There is a doing that guides you. As you grow up, you encounter that this is actually a method of seeing your body in relation to the cosmos and that’s when it acquires its true political, cultural meaning. When I became aware of what I’m telling you now, I had already been doing it for a very long time.

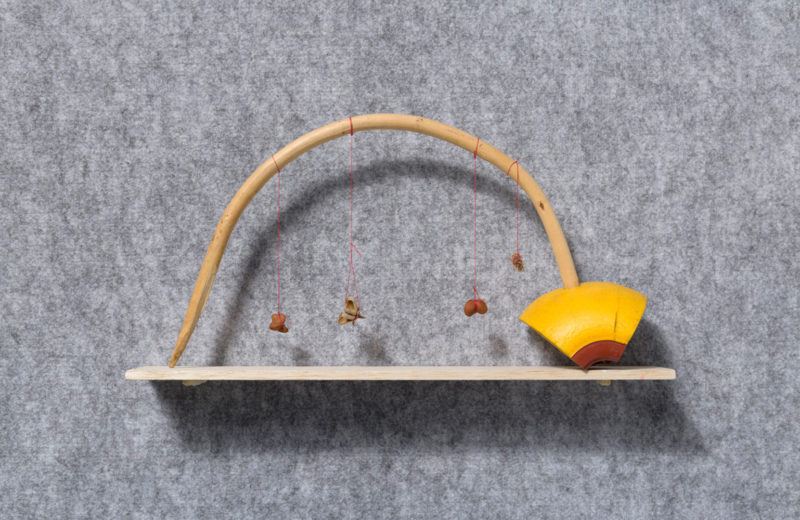

The precarios began in the same way. I had finished high school, I was a 17 year old girl, and I had been accepted in architectural school. I was dreaming of an architecture that could be a form of poetry in space for the entire city, for the entire world. But how do I express that? I did it in miniature with little pieces of debris and I did it by the beach to be erased by the sea. All the concepts were condensed in this act: the notion of an architecture that functions in nature, with nature, in collaboration with the sun and the ocean. This is the scale that I am envisioning—an architecture, a universal architecture, but the language of it is minute.

You and your work have long had a relationship to water. Why do you think that is?

Our culture pretends to have forgotten that we are water and that without water, we cannot be. I was lucky enough to grow up in the countryside and we had a big acequia, a big irrigation canal that passed a few meters from my room as a baby. I grew up hearing the music of water and little frogs that sang every night.

This devotion to water, what it does for feeding us, what it does in terms of transforming itself into another dimension like sound or light, how light is reflected in the water. Water is not just water, it’s a teacher at the same time. I began working, playing with water, learning from water.

As you can see from the start of my art, I was collaborating with the sea, doing work for the sea to see. The sea came and swallowed it. I was so satisfied because we had entered into a dialogue, like the water was saying, “I see you, too.” This is the beauty of what has been given to us by this earth, by the cosmic existence of water. As far as we know, we are the only ones that have this gift of liquidity. How can we not live in awe or reverence to that relationship?

Knowing you have this profound reverence for water, how do you respond to issues of climate change?

The Americas have been the place of plunder, colonization, and extraction for more than 500 years. We’re still in that mode where the total destruction is bringing us closer to human extinction. We already knew about this climate destruction in the 1960s, but it has only become more intense, more painful, and more urgent. Why are we in this race to destruction? How is that supported by indifference, by looking away? My work is a way to look in, to invite firmly to look in.

Until we see a real move towards reversing this destruction, we cannot be hopeful, but at the same time, something in us wants to believe that as long as there is a thread of water, a thread of life, as long as there is a woman able to give birth, there may be a chance. But the threat of things going awry is becoming stronger and stronger. Being at the edge causes these moments of experimentation and discovery in the making of art. It becomes more precious and more meaningful.

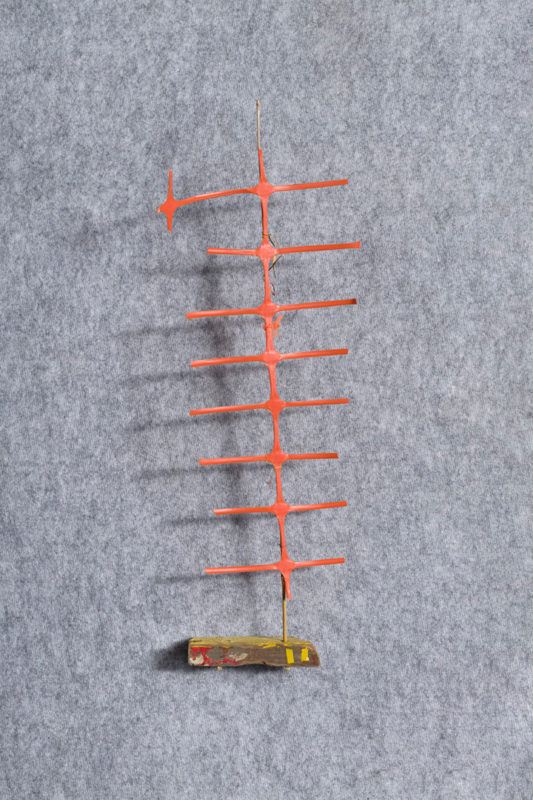

Tell us more about your quipus and how you first started making them.

When I was growing up, indigenous knowledge around quipu was utterly and completely erased. We didn’t have it in museums, we had no books about it, it was not part of the curriculum in schools or universities. But I had an aunt who was an artist and had foreign books. It was there that I encountered the quipu when I was a teenager. This image of this strange, knotted cord must have done something for me because I went home and I imagined a quipu and I wrote down the phrase “the quipu remembers nothing.”

As a teenager, I understood at once that this was a form of knowledge that had been erased and that I wanted to recover it. I didn’t read anything about it. Just the image of it, the morphology, the structure, the shape of it did something for me. How is it possible? Where does this come from? I say it comes from the memory of the hands. It comes from an ancient tactile memory that is like a jumping board for imagination. I can tell you that without any so-called knowledge, something in me knew. I think that is what makes art be art. That something in us knows without knowing.

How do you make decisions about size, color, etc. when making the quipus?

New discoveries keep emerging of how many variations of quipu there existed. And somehow, the memory of my fingers recreated most of those forms without ever having seen them because that information was buried. So, that’s why I think the real question is how does that information travel and transmit?

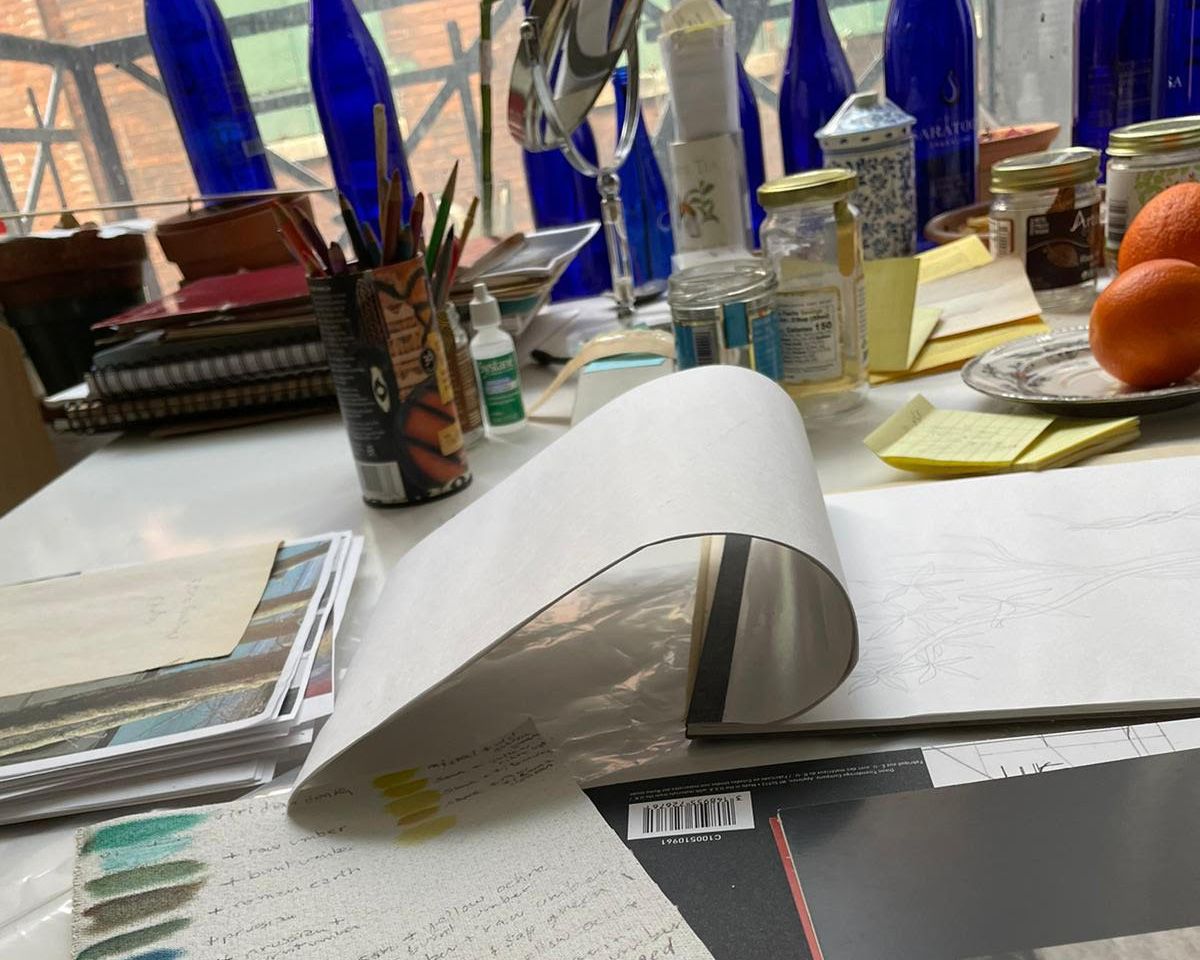

The main tactical decision for me is to open up to that form of understanding or feeling that exists in you. It exists in your own fingers, in your imagination, in your dreams. The art exists in learning how to listen to that, because it’s not something that you are taught. No one can teach you how to do that. You have to discover yourself, how to pay attention to those very delicate threads of imagination.

One way that I sort of train myself is by working with impossible issues. For example, the quipu that I made for Documenta is an impossible construction because it is made of unspun wool. Nothing holds it together. How can you make it go up ten meters without it breaking? Because there’s no answer for that, I dream of the solution. So where is the practical imagination? It’s in the training to focus your attention on what’s the most impossible, invisible, undoable.

Do you have practices that help you to train your imagination to do that?

Yes. The main one is, do nothing. The main one is, just have fun and just don’t listen to anyone. Don’t pay attention to the pressures, the expectations, all the things that are foreign to that instinct, that light that is contained in what is impossibly difficult.