Kathy Cho—You have your first solo exhibition in New York coming up through the A.I.R. Gallery Fellowship. Tell us about your research and what you’re thinking about in the studio.

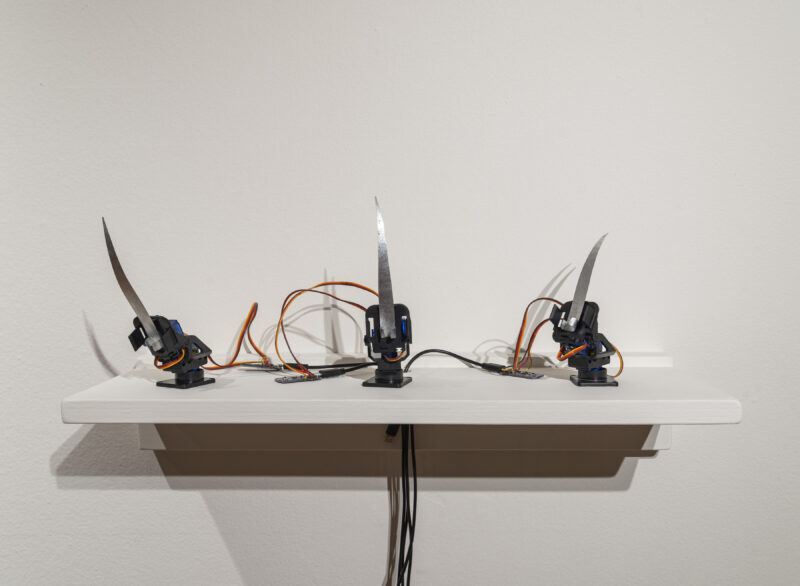

Caroline Garcia—I’ve been thinking about mourning methodologies and funerary rites, as well as the spiritual aspect of practicing martial arts, which I feel called to after years of dedication to physical training. What has been most consistent for me in the studio is a focus on technology, both ancient and digital, and thinking about the living past in the present while embracing a nonlinear continuum.

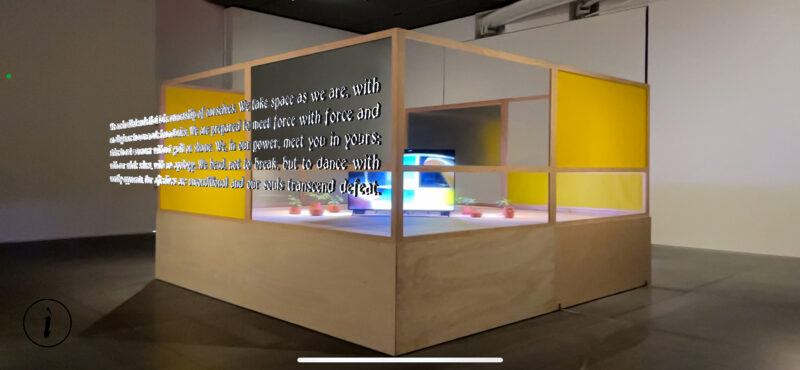

This upcoming solo exhibition is an opportunity for me to engage with a more personal narrative in a very intimate gallery setting. Lately, I’ve been consumed by the existence of a parallel spirit world and the interconnectivity of preternatural and physical planes, which I began investigating last year when I created two new works: A Supersonic Requiem and Fair Warning to the Gods. For the A.I.R. Fellowship, I am revisiting the idea of holography, which I’ve experimented with twice in the past, and will be creating an installation that generates a holographic effect, using a pyramid-shaped scaffolding that is a variation of what is commonly known as “Pepper’s Ghost.”

I first encountered holography as an artwork at the Taiwan Pavilion in the 2015 Venice Biennial, which featured an exhibition, Never Say Goodbye by Wu Tien-Chang. I was deeply fascinated by Tien-Chang’s simple composition of glass and focused lighting to reflect a sculptural figure concealed above eye level, which created an apparition in the gallery. Though I was aware of how it worked, I was still captivated by the ghostly illusion. It seemed to allude to another plane, simulating the past or a different time in the present to speak to parting ways in life and death and what Tien-Chang describes as the in-between aesthetic of yin and yang. I will be employing similar themes in my holographic rendition as a means to bring together magic and religion in a way that annihilates space and time while inviting the phantasmic to travel through the realms of instinct, intuition, and perception.

KC—How do you plan to work with these ideas in this upcoming exhibition?

CG—There are several components and approaches to developing the central installation of this exhibition. Firstly, the holographic imagery will be digitally generated through 3D-modeling, with an option to use 3D scanning in the process, which aligns with more traditional holography that is typically used in physical 3D objects.

Secondly, the imagery presented in the 3D-rendered video will be sourced psychically, through readings from spiritual mediums as a means to communicate with my late mother. The idea behind this collaborative approach is an effort to build a metaphysical archive. When we remember people who have passed, it can often be limited to material records and the memories we hold. There is a sense of melancholy that overcomes me when the remembrance and preservation of my mum’s life is limited to her lifespan on an earthly plane. This initiative to expand on a metaphysical archive augments and transposes communication between realms to conjure a speculative record of her life after death, so that my grief and memories are not lost in linear time.

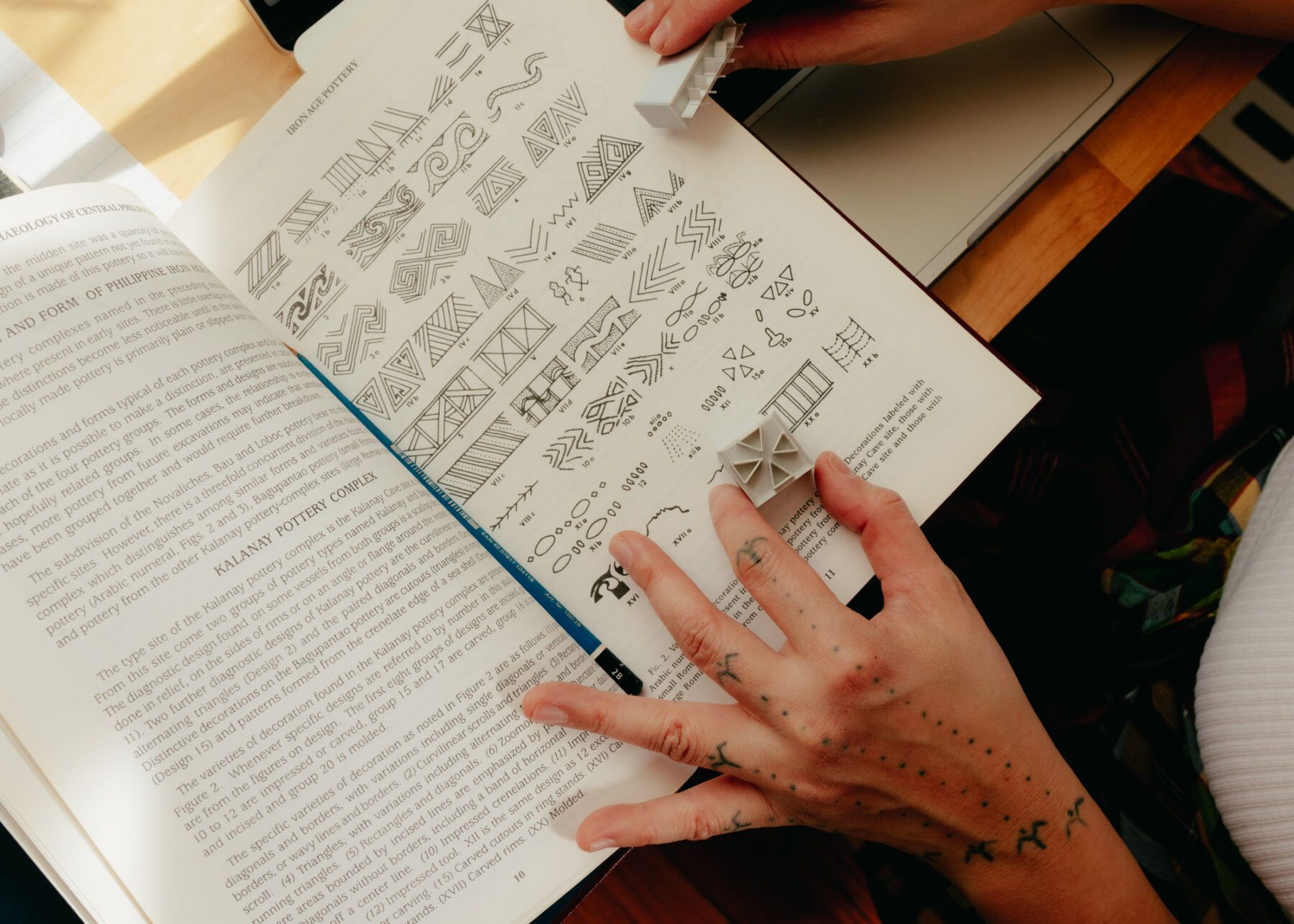

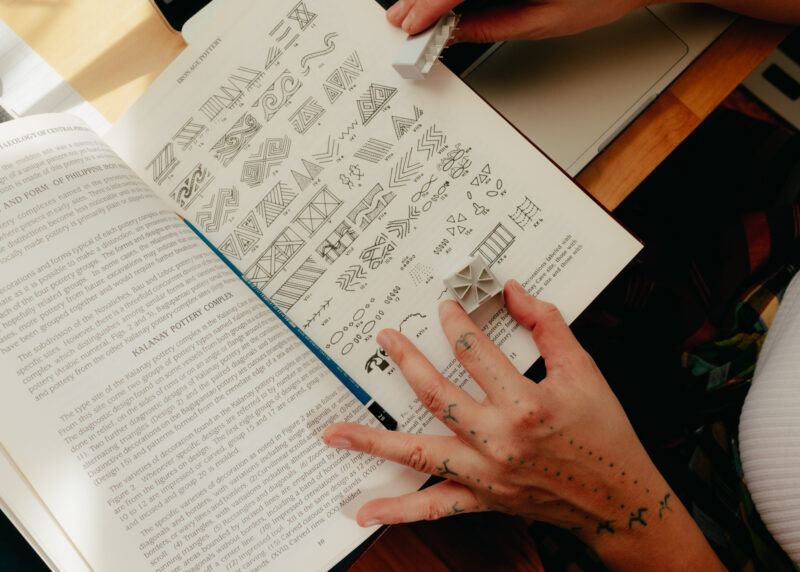

Lastly, I plan to construct the installation using natural materials such as bamboo, iron steel, and stingray barbs to incorporate the notion of magical warfare technologies into the piece. The objective of magical warfare is to provide protection or defensive strategies to appease unsettled spirits. By including these materials, I am observing the custom of guarding the departed from malevolent spirits by interring them with talismans, weapons, and agricultural tools, which was widespread throughout the Archipelago.

KC—I’m often curious about why artists decide to work with technology as a tool to visualize or expound upon immaterial or spiritual practices. What are your methodologies for incorporating such a quickly evolving field?

CG—I’m definitely no expert when it comes to new media; in fact, I’ve labeled myself as a “tech faker,” even as I work on expanding my skill set. As my core foundation is in movement, I intuitively lead with the body first. Therefore, my approach to working with tech is always filtered through an embodied framework. The probability that I use digital technologies incorrectly, imperfectly, or even in ways that it was never intended for is extremely high. To me, these errors, failures, and glitches are embraced in my very DIY and human-centered aesthetic.

With this in mind, I think what keeps me drawn to experimenting with digitally based outcomes is that it offers me a kind of distancing and permeability. I’ve found it can be a useful and versatile tool for attending to unresolved concerns and questions that I’ve been unable to answer related to navigating my own transpacific identity both within the diaspora and my relationship with indigeneity—which is inherently embedded with lateral violence.

In the early stages of my practice, I developed an obsession to prove myself through ethnographic authenticity and competency to fill in my experiences of non-belonging and displacement. I came to realize that the gaping loss of cultural context in a (im)migratory narrative was a very difficult space to fill. I then thought about shifting the questions of authenticity to a process of being authentic to the research, and I suppose this reframing is how I arrived at using new media. I continue to find value in the miscommunication and misconnection of digital signaling and data processing as a means of protection from committing transgressions against indigeneity or ancestral betrayal.

In my practice, I never intend for technology to function as a replacement or substitute. I’m more interested in how it can be used to carry the weight of my personal and inherited loss, specifically as a surrogate for ritual and for the transmission of immaterial practices, especially spiritual systems. There is opportunity for the distancing to be harnessed, in which the digital is a hegemonic tool that can be exploited and fetishized as a sacrifice for my ancestral needs. Working with new media feels like both the poison and the cure, a tactical and diasporic dance that recuperates invisible violence for safety, defense, and survival.

KC—How does your embodied practice of Filipino Martial Arts and use of time based mediums lend itself to the goal of seeking protection, while simultaneously exploring the symbiotic nature between the spiritual and physical realms?

CG—This inquiry into magical warfare technologies was the product of shifting my Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) research from physical and somatic, to spiritual, psychic, and esoteric. In fact, the very last category of weapons in the Inosanto LaCoste Kali system that I study is listed as mental, emotional and spiritual training. This comes in twelfth place, after sticks, knives, empty hands, long weapons, flexible weapons, throwing weapons, and flying projectiles. Interestingly, mental, emotional, and spiritual skills might be the most difficult to teach and learn, and it is these immaterial tools that are most unique to Philippine culture and instrumental to the survival of Filipinos.

Another example of what I consider as magical warfare technology is Orasyon: a special prayer, incantation, or mantra that is a psychic tool and oral tradition for defense and protection recited mentally or verbally before battle. Also regarded as a form of anchoring in neuro-linguistic programming, whereby a stimulus triggers a response (in this case, the psychological triggers the physiological). Most importantly, the efficacy of this method requires belief and intention from the orator to access psychosomatic and energetic power. I explored Orasyon in my 2023 augmented-reality piece, Force Field, which presents a protective prayer that was co-authored in 2021 by members of The Chrysalis Kali Collective: a group of Filipina/x women and gender expansive femmes, with whom I train in FMA as an empowering mind, body, spirit practice.

KC—You have previously dealt with themes of grief and matrilineal loss in your work, how has this ongoing research evolved throughout the years?

CG—Honestly, to this day, I continue grappling with my mum passing in 2016 and at times it feels easier to disassociate than be overcome with emotion. Understanding the implications of such a cosmic loss really does feel like a never-ending process. It actually scared me to make work about something so deeply personal and present it publicly. In hindsight, I realized that my way to contend with this fear was to codify my process of mourning so that it was almost unrecognizable as grief. I experimented in this way for an installation commissioned by The Shed for Open Call 2021 and after receiving ambivalent reviews, I became curious about the expectations of how grief is typically understood to look and feel. To be frank, these conventions did not entirely resonate with my experience of matrilineal loss.

Around the time when my Mum was diagnosed with cancer in 2015, I came across the Manifesto Antropófago by Brazilian Poet Oswalde de Andrade. I also traveled to the Philippines alone, the first time since visiting with my family as a child. My itinerary began with eating at Jolibee, a well-known Filipino fast food chain, and then island hopping before meeting up with a group of artists and activists. Alleluia Panis, my mentor, organized a program for us to have meaningful exchanges with Indigenous culture bearers in Mindanao in the Southern Philippines. This was incredibly transformative for me as an artist of the Philippine diaspora and many of the ruminations from that trip resulted in a closer inspection of the Cannibalist Manifesto and the 1960s Tropicália movement that it invoked. My visit spiraled thoughts about collective loss from a pre-colonial perspective, the forced assimilation of the living Indigenous people, stolen sovereignty, cultural and ritual displacement in the diaspora, and the ancient grief held in our bodies.

During the research phase for my earlier video works, I was also reading bell hooks who cited Renato Rosaldo’s essay, ‘Imperialist Nostalgia.’ Influenced by his critique, I delved into Rosaldo’s book, and discovered the introductory essay, ‘Grief and the Headhunter’s Rage.’ This spurred what is now about a six-year investigation into ethnographies of death, psycho-spiritual ritual, and mourning rites that involved head taking and ceremonial cannibalism. Rosaldo conducted research on the Ilongot tribal people of Luzon in the Northern Philippines and his field studies provided a complex analysis of their way of life as salient headhunters. I was so compelled by such an incongruous pairing of grief and headhunting. Rosaldo describes a “cultural force of emotions” in grieving as the motive to take a head. Amongst other Indigenous Philippine motives for headhunting that I researched, one that stands out to me is to provide the departed with a companion to travel to the afterlife.

This research trajectory of motives led me to a current investigation of how our brains process grief. Neuroscientist Mary Frances O’Connor suggests that grieving is not just about having an emotional response to loss, but an active craving or yearning for the lost connection. She proposes that a grieving brain is in a motivational state: because the brain is hardwired to form attachments, O’Connor recommends a route of healing by redrawing one’s neural map of the attachment bond, which exists in three dimensions of space, time, and depth of connection. As I borrow from this research, holography feels more and more legitimate as a guiding tool to participate within an Indigenous spiritual matrix. Working on this upcoming exhibition, in a way, reinforces a new neural remapping of the bond with my mum as we continue to collaborate on an archive of her afterlife.