In the Studio

Buck Ellison works to get toward the truth.

Jurrell Lewis—What drew you to portraiture as a way of making?

Buck Ellison—I switched from making still lifes to portraiture in my graduate thesis show at Städelschule, in Frankfurt. I showed one work, and it was a portrait of one of the students. I remember the difference in the way that portrait was received and the way that a still life was received. It hadn’t occurred to me that people really like to see themselves in other people. The engagement that allowed excited me because it felt like I could bring in a viewer on many different levels. That was a real turning point for me.

I moved to Los Angeles shortly after, and that’s when I began making the work that I think is more familiar as my work now—I’m not shying away from the power of reproducing another person. The discomfort in that is that I’m shy, I don’t like approaching people, and I’m sensitive toward the labor of the sitter and what my gaze does, all of those dynamics. But anytime I’m uncomfortable, I think, Okay, I’m doing something right.

I started working with actors and models, and that felt more interesting. There was this whole group of people who were open to coming over for four hours in the middle of the day for a project, while before it was difficult to find people to shoot. Anytime we see a face, we want to look again. Moving here allowed me to use portraiture, to use that engagement from the audience. I could start to use that to be able to do other things, to look at behaviors and patterns and to reveal little things. I don’t see them as dissimilar to the still lifes, they just have people in them.

Do you think about the history of portraiture or its function in popular culture when you’re creating your work?

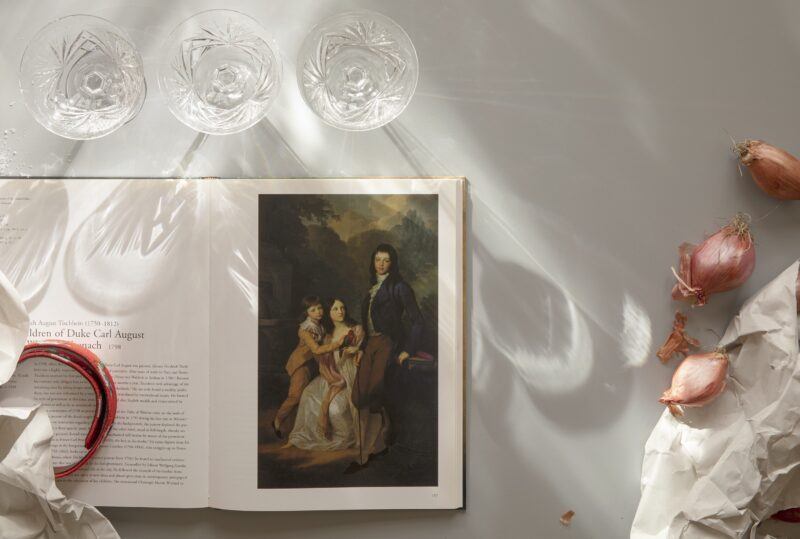

Something I think a lot about is early colonial American portraiture. The artists who couldn’t hack it in England came here, which is why you’ll often have a family portrait where the baby is bigger than the wife. These are really interesting documents. They’re beautiful to me. One of the main functions of this portraiture was to depict the smooth passage of power from one generation to the next, and we almost never see them hung in the context they were intended to be used, displayed in the home.

I think about portraits as, from the get-go, linked to power, whiteness, the institution of marriage, and the merging of families. When I make a family portrait of white people, I think about that a lot. I try to upend that and think, Okay, well, it’s a family portrait, but it’s completely fake. The people in this photograph just met two hours ago. The final image is being composited from multiple images. I think about how perverse that is, that very standard advertising technique. These families that make us feel so bad about ourselves, the perfect families, are a complete fiction. I think that’s a really fun thing to play with.

I think about the Christmas card a lot, which is, in some ways, a contemporary version of that internal document, the portrait in early colonial America. When I say internal, I mean that people would come to your home at that time to be entertained, and they would see the portraits, which do little things to signal to the viewer. A merchant might have a sea with a ship in the background of their portrait, and the man of the family will be pointing at the ship. In a Christmas card, you might see a family on a beach in Turks and Caicos, and everyone looks amazing, and they hired a professional photographer. It’s internal, but it’s signaling something, and they send it to 700 people.

This production of desire and aspiration exists in your photographs, and I’m curious how they function in your larger project examining the codes around wealth.

The desire and aspiration to be wealthy is something that we need to interrogate in our culture. Sociologists call this “luxury creep.” A normal house in a movie will be an eight-bedroom mansion, and it goes completely undiscussed. It’s just understood that that’s a house. How damaging is that? How politically convenient it is for a moneyed class to have everyone else persecuted, penalized, and jailed for their lack of money but then condition them to still have such a deep admiration for that moneyed class. Advertising has a hand in that, but it’s also from our language and the beginnings of our history.

Thinking of advertising, my photographs are also posed. A certain level of constructedness or overperfection is important in having them be read as characters rather than real people. I think about replicating the world as it is: Wealthy people tend to be fit and have every possible cosmetic procedure available to them, so that felt like something to faithfully reproduce in my photographs. That’s really stressful. I’m very aware that I’m producing images that exclude a lot of people, but that might be the point. That’s what I’m trying to talk about here. Who does this silence around wealth serve? Who is it for?

Your work points to the larger systems or structures that perpetuate wealth and secrecy around it, and one way you do this is through the use of nonspecific individuals in your portraits. Could you talk about that?

The nonspecific was an attempt to focus on the systems and the networks, the behaviors, rather than the individual. So much of what motivates this work is things I overhear or see, the tiniest little gestures. The way this woman put a pint of blackberries into her grocery cart, or friends interacting with staff with a benevolent paternalism. You can feel the guilt there, how palpable it is. We can judge individuals, but essentially what we’re saying right now is that as long as rich people are nice, it’s completely fine that we live in a country with this many billionaires and this many people who can’t feed their families. But that’s the part that should be unacceptable.

Erik Prince and Betsy DeVos, those series were just another way of going at it. They are very specific, and yet I think Prince is certainly not the first white man to go to the Middle East to win his fortune.

How do you cast actors and models for these shoots, and how do you work with them to achieve the final image?

Something really bizarre I noticed is that actors are very excited to play wealthy people, but when I’ve cast for nannies or tutors, no one seems as enthusiastic. That points to how we’ve been socialized to hate the poor in the United States, and how we’ve been socialized to glorify the wealthy.

But what do I do? I set the scene up, and I don’t tell the models much about who they are or what they’re doing. I sometimes think of the work as performance documentation. The models often slip into roles in this way that’s really amazing and uncanny. I have a lot of admiration for these models who work with me, for taking the time and for participating in something that is uncomfortable. I think artists don’t acknowledge the labor of the sitter and what they do enough. It’s particularly important in my case because the photographs are so movement-based. Things like this model’s hand in Mama (2016). The model did that on her own, and then I get to take credit for it. I mean, I selected this image from 5,000 different pictures, but the models bring an element of surprise to the process.

Something I’m curious about in your work is whether or not the camera or the image produced allows a certain empathy for or understanding of the subjects.

I don’t know about the machine itself, but I hope my work is doing that. Empathy just has to be bracketed here. This practice is a tool for getting toward the truth and not participating in moral judgments of individual behavior, just looking at the photographs. I always say the work is about looking with tenderness, and that felt extremely necessary for Betsy and Erik. For the more behavioral ones, I’m thinking more about the way to do this as precisely as possible, as accurately as possible. I have a real responsibility as an artist, given the subject matter and the radioactive way these images could be received, to at least get the details right and hopefully invite people into that conversation so that these behaviors don’t just remain systems of maintaining power.