Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Performance.

Performers: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Matteo de Mayda. / Pret-à-Patria, 2024, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Actuación.

Intérpretes: Jhoav Stuart Molina Garcia; Kevin Adrian Beltran Villa.

Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte-La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere. Foto de Matteo de Mayda.

Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fiberglass, resin, steel structure, and polyester.

560 × 63 × 170 cm. Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery. Photo by Nick Ash. / Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de Kurimanzutto Gallery. Fotografía de Nick Ash.

Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fiberglass, resin, steel structure, and polyester.

560 × 63 × 170 cm. Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery. Photo by Nick Ash. / Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de Kurimanzutto Gallery. Fotografía de Nick Ash.

Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fiberglass, resin, steel structure, and polyester. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery. Photo by Nick Ash. / Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de Kurimanzutto Gallery. Fotografía de Nick Ash.

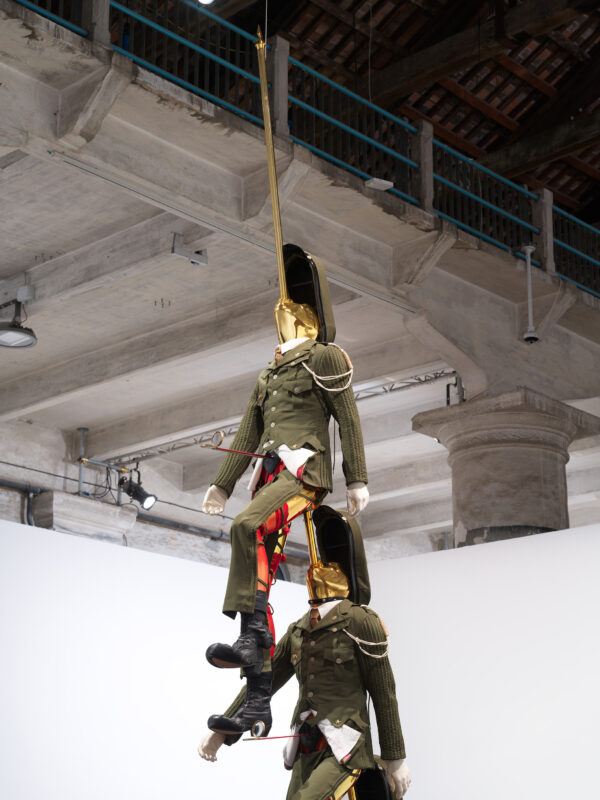

Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fiberglass, resin, steel structure, and polyester.

560 × 63 × 170 cm. Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art

Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. / Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de Kurimanzutto Gallery. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura de acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere.Fotografía de Andrea Avezzù.

Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fiberglass, resin, steel structure, and polyester.

560 × 63 × 170 cm. Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery and the 60th International Art

Exhibition–La Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque–Foreigners Everywhere. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. / Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de Kurimanzutto Gallery. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura de acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de la Galería Kurimanzutto y de la Sexagésimo Exposición Internacional de Arte Biennale di Venezia,Stranieri Ovunque-Foreigners Everywhere.Fotografía de Andrea Avezzù.

Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fiberglass, resin, steel structure, and polyester.

560 × 63 × 170 cm.

Photo courtesy of Kurimanzutto Gallery. Photo by Nick Ash. / Pret-à-Patria, 2021, Bárbara Sánchez-Kane. Fibra de vidrio, resina, estructura acero y poliéster. 560 × 63 × 170 cm. Foto cortesía de Kurimanzutto Gallery. Fotografía de Nick Ash.