Jenny Wu—How did this collaboration among the four of you—Lovely, Gabriella, Warren, and Tammy—first form?

Lovely Umayam—There were layers upon layers of convergences and serendipity, but because of the themes that we’re each attracted to—nuclear landscapes, plant life—it felt like an organic convergence.

Together as Atomic Terrain, you’ve produced the artists’ book How to Make a Bomb (2024), which is simultaneously about horticulture and nuclear history. Its title is provocative, but what is the book really centered on?

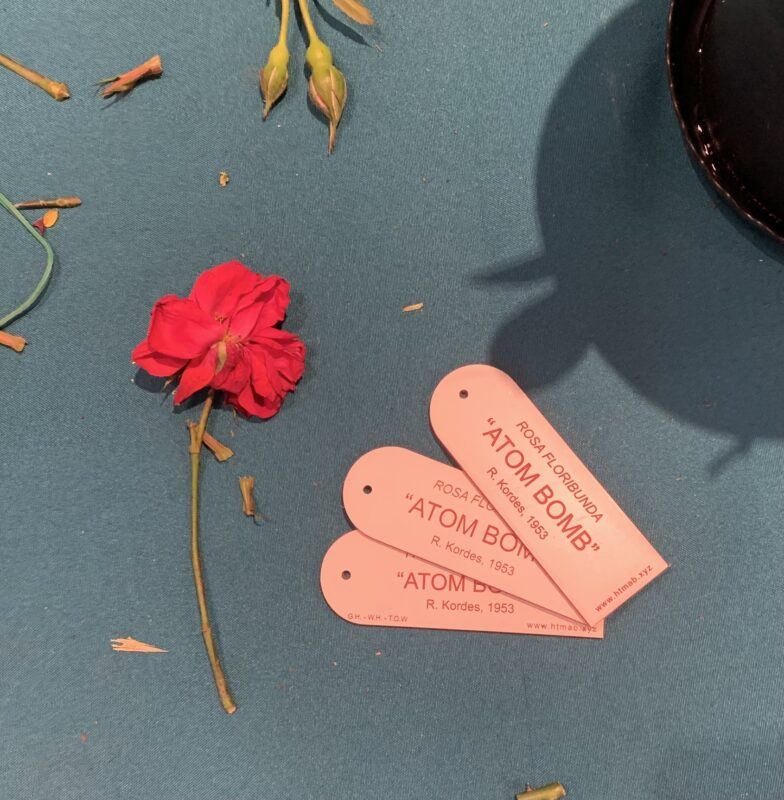

Gabriella Hirst—The book’s central figure is the Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb,” a garden rose that was cultivated and named in 1953 during the Cold War arms race to commemorate Britain’s newfound status as a nuclear power.

JW—Why, besides its name, did you decide to use this rose as an entry point to examine nuclear issues?

LU—Nuclear issues alone can feel abstract and alarmist. It’s easy to get carried away with theory and war games. You either see an atmospheric nuclear test, à la Oppenheimer, or you don’t think about it at all. But there are lands all over the United States that are contaminated because of nuclear weapons and improperly stored nuclear waste. Both the US and the UK are currently modernizing their nuclear weapons. The price tag for the current nuclear modernization effort in the United States just surpassed $100 billion.

GH – Our project is about taking the sublime into your own hands and working through that in small ways. How to Make a Bomb, being a pamphlet, plays with the history of nuclear how-to guides (think: “How to make your own shelter”). It works in gentle ways to reduce fear among non-experts.

Did you know from the start that your interest in Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb” would lead to a publication made by the four of you in the US?

GH—The project was at first about the nuclear relationship between the UK and unceded Indigenous lands in Australia. Between 2016 and 2022, Warren and I developed a practical rose grafting guide, which included a bunch of research and infographics. The guide was a separate publication, very small and informative and intended as a practical guide for disseminating Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb” in the UK.

Warren Harper—At first, I was interested in nuclear sites in Essex, where I’m from, and what role contemporary art and curatorial practice could have in thinking about these sites. The Old Waterworks, an artist-led center in Essex where I was director at the time of my initial collaboration with Gabriella, is near one of the UK’s atomic weapons research establishments. That site is where Britain’s first atomic device was assembled before it was sent to Australia to be detonated.

Tell me about your first encounter with the actual Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb.”

GH – I learned about Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb” in 2015. Immediately, I wanted to know what it would be like, as a time-based practice, to tend to this rose with this extremely violent name. I tried reaching out to different nurseries in Berlin, where I was living at the time, and discovered that it was extremely hard to get. Although it had initially been quite popular, it hadn’t been in commercial circulation for a long time. Some remaining specimens were held in specialist collections in Eastern Europe and Italy. A representative from a collection told me, “We just have one of these roses in our collection. Grafting takes two years, and it’ll cost 40 euros plus postage.” I loved that it was so banal.

Two years later, after I’d moved to the UK, I received an urgent email saying, “Your rose is ready.” I went back to Germany, where I received this rose as a bare root—a body disconnected from the soil. When I brought it through the airport in my luggage, I was anxious because it had a little label that read, “Atom Bomb.” I realized, then, that Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb” was inherently political — not only in its name but also in terms of how it moves around the planet.

When did you realize you needed to graft the rose and disseminate it widely?

GH—As I was taking care of it in the UK, out of my fear that I would kill this one Rosa floribunda “Atom Bomb,” I felt I needed to make more of them. Hence, the project How to Make a Bomb (2015–ongoing) was started, which was about teaching other people how to graft this rose and plant it guerrilla-style in UK gardens. The point was that these roses would go out, and maybe their atom bomb labels would fall off and maybe they’d die, or maybe they’d self-propagate and become other plants. I often think of gardens as books: they’re embedded with language, and they grow and change over time.

How did the rose then make its way to the US?

LU—As Gabriella and Warren were developing their project in the UK and Europe, Tammy and I were creating a nursery of nuclear plant life in the US. For inspiration, we were looking at ginkgo trees in Japan that survived the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings in 1945, and sunflowers, which were this symbol of nuclear arms control between Ukraine, Soviet Russia, and the United States back in the early ’90s. We thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool if the Rosa floribunda ‘Atom Bomb’ became part of the nursery?” And that prompted the creation of Atomic Terrain. The process of importing the rose was another story.

How so?

LU—You can’t bring certain plants when they’re with roots. They have to be quarantined — understandably, because of potential environmental impact. But if we went that route, that could’ve taken between six months and two years, and no one could tell us what the specific timeline would be for roses.

GH—We found a loophole: You can graft from the branches of the rose itself. We spoke with a national parks expert on invasive species to make sure we weren’t doing any ecological damage. Then I made a bouquet of “atom bomb” roses that I wrapped in a box in beautiful paper, with a note that said it was for a wedding. I brought the bouquet on the plane, which you’re allowed to do. In the US, we declared the bouquet to customs and they said, “Have a nice wedding.”

Does this story feature in the book?

Tammy Nguyen—The narrative of How to Make a Bomb (2024) is split into three sections. In the US edition, the third section is all the different acrobatics required to get the rose into the States, including facsimiles of documents like the Department of Agriculture’s application for plant permits. The first is the context for the work, including Cold War history and up-to-date statistics about the worldwide total inventory of nuclear weapons. The second is how to graft a “bomb,” which metaphorically equates the rose with the bomb. The making of that mythology is exciting because rarely is something so abstract and simultaneously so memorable. There’s something special about that collision of rose and bomb, peace and war. To quote a line from an essay that Lovely wrote: “To tend to life, even if it is nothing more than a rose, one must assume ownership, get messy, and accept the chance of failure. One must take responsibility for the possibility of killing something.”

Since the narrative is only one facet of it, can you also tell me about the visual and material choices you made for the book?

TN—The structure of artists’ books is exciting because it offers opportunities to demonstrate simultaneity. In a conventional book, you’ve got this elegant spine that allows for many pages to be attached through a unified structure, but artists’ books break that convention by making it normal to cut and paste and stick together and unfold and wrap up many different ideas of a spine.

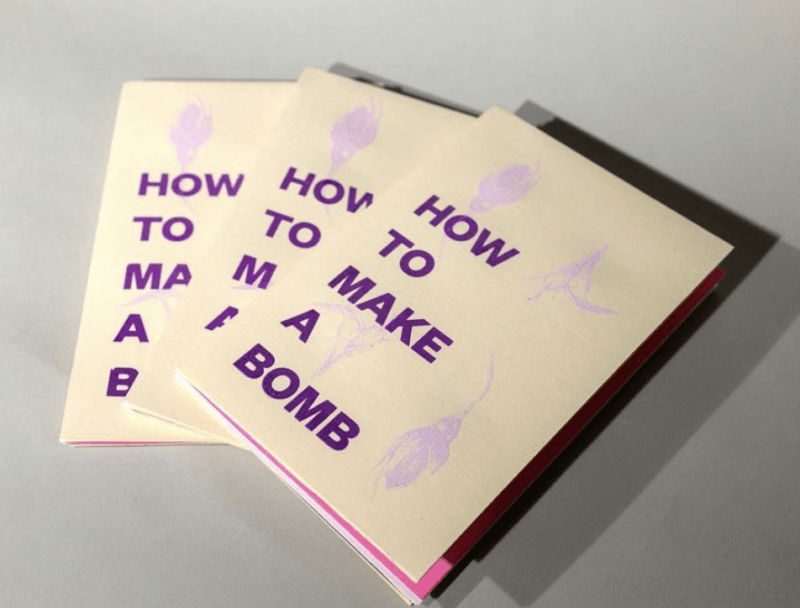

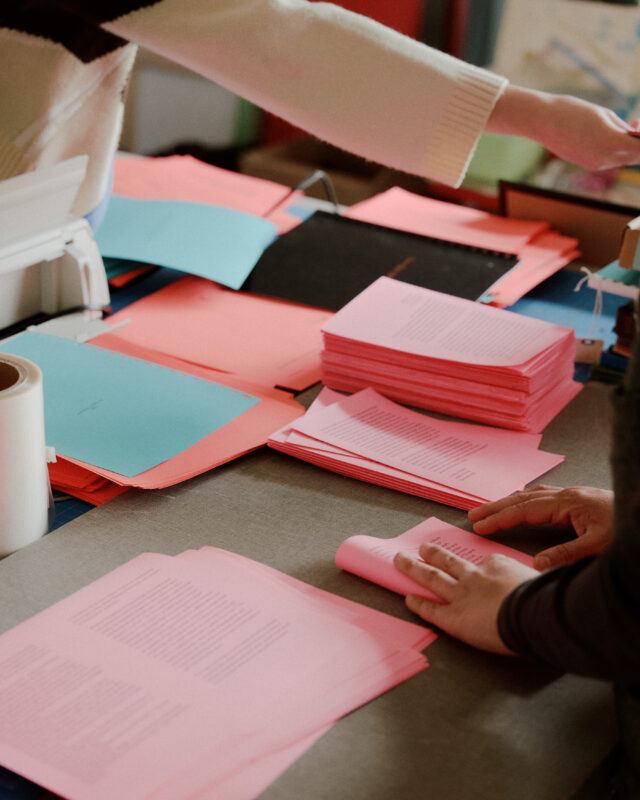

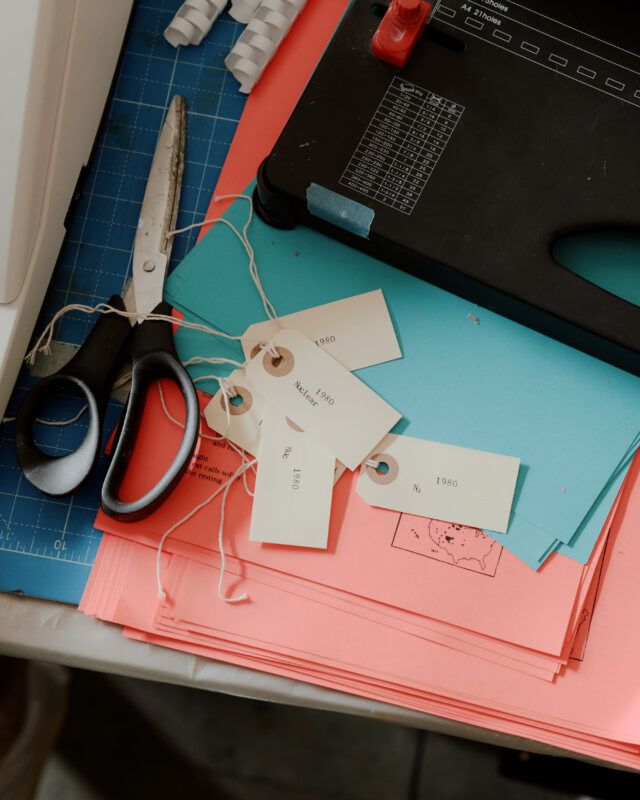

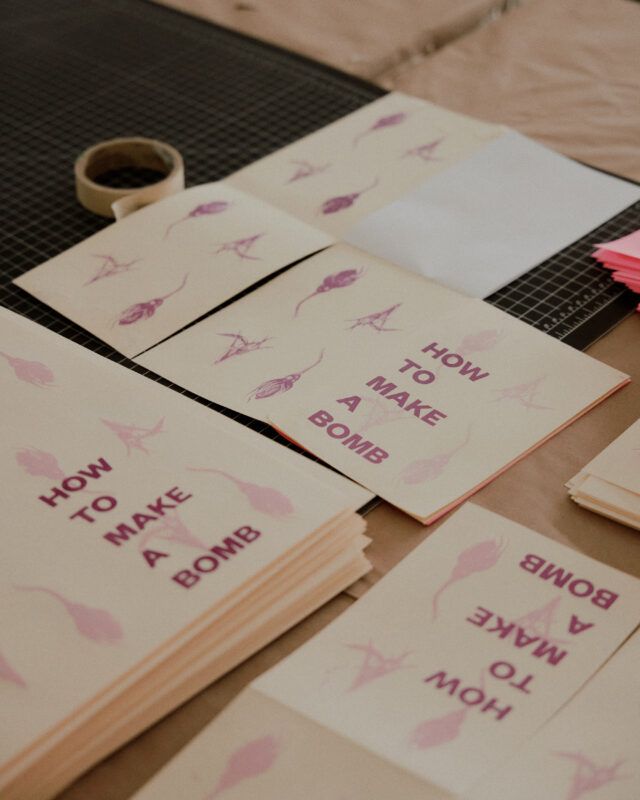

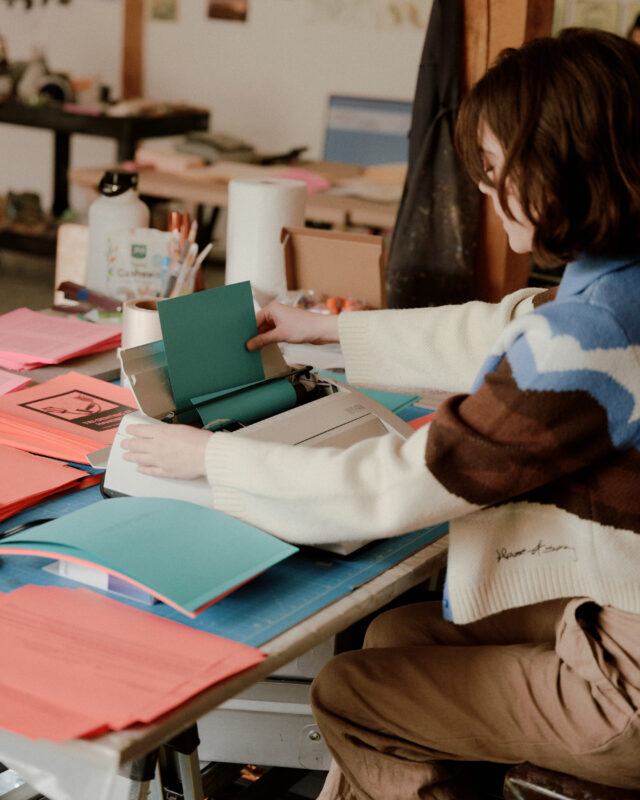

How to Make a Bomb is a publication that begged to be a democratic multiple. The challenge was to make it in a clever way that was affordable to us and to the public while retaining a handmade quality. The structure of the pamphlet is a single continuous piece of 18-by-24 posterboard. A couple of slits are made, allowing it to have different pockets on both sides. Then each pocket, because it folds back into half of an 8.5-by-11 sheet of paper, lets us split up the narrative into its three sections.

Can you show me some hidden details in the book?

TN—The graphics on the cover look lavender, but we’ve used silk screen ink that has reflective particles in it. If you photograph the cover with flash, it flashes white. That’s a classic Passenger Pigeon Press strategy—hiding some special effect through ways that appear very ordinary. It’s one of those things that hints at the sublimity of nuclear landscapes.

Where can I find a copy?

TN—Atomic Terrain is going to be in the project space at the New York Art Book Fair (April 25-28, 2024). When you come up to the project space, we’ll be grafting roses at different times of the day. There’s also going to be a library—a very touchable, soil-y, dirty library filled with everything from government documents to research books. We hope you’ll come play in the dirt, graft some roses, and read some books.

What role do events like the New York Art Book Fair play in terms of disseminating knowledge and expanding access to art?

TN—I’ve been going to the New York Art Book Fair since I was a college kid at the Cooper Union and consider it one of the happiest places in the art world. There’s this speed, this energy, with which artists can, by their own means, put out content relatively quickly using modest technologies like photocopy machines and stamps. Everything is hand-done: you’re stapling it, you are punching holes in it yourself. There’s none of the bureaucracy of having to work with a publisher. There are also major publishers who exhibit at the festival, but I think the spirit of it is embodied by artists’ books that are for the most part made this way.

LU—Since I’m not an artist but instead a nuclear policy expert whose research involves looking at how arts and culture inform policy, spaces like the New York Art Book Fair have been great sources of data for me for thinking about public opinion and the public understanding of nuclear issues. I don’t get that in the DC think tanks I frequent. We have big access issues in the nuclear policy field. Often when I do my research, it ends up in a 65-page PDF that no one reads except my colleagues in my little academic policy bubble.

GH—It’s also one of the more inclusive places in the art world. Even though artists’ books are made in small editions, often they travel and their inclusivity spreads to more people outside of that space.

TN—Then again, there’s probably only ten copies, and you probably might’ve only heard of it through word of mouth. I don’t know if that’s a bad thing, but it is exclusive. In Vietnam, where there’s a huge issue with artistic censorship, artists’ books have been extremely meaningful to folks working in censored contexts. Because they can travel so easily, they can be passed along like a love note.

WH—There’s a special relationship between a reader and a zine that’s one of 50 copies due to limited materials or time. To have that form of intimate engagement with a book is quite distinct.

What’s next for Atomic Terrain?

LU—To use the analogy of a nursery, Atomic Terrain doesn’t just stop at one plant. I’m continually receiving information and stories from people on related topics. Someone was just talking to me about the juniper bush in the Navajo Nation and how that’s connected to nuclear contamination. When we give away roses—and hopefully we do that at the New York Art Book Fair—the project takes on a life of its own, one that is now between the rose and the person who decides to take it.

GH—The roses are out there growing. Sometimes opportunities for events and exhibitions present themselves, and sometimes for years it’s just you taking care of the rose.

LU—I think that, too, is a manifestation of the artwork.