In the Studio

Alanis Obomsawin tells another story.

Max Levin—You were born during a solar eclipse on Wabanaki territory, in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and have lived most of your life here in Quebec.

The Children Have To Hear Another Story — Alanis Obomsawin opened in Berlin in 2022 and is now on view at MoMA PS1 until the end of August.

How has it been to see your life’s work gathered in these exhibitions?

Alanis Obomsawin–When I saw the exhibition in Berlin, I couldn’t believe it. It was incredibly well-exhibited and I was very impressed. Then it came to Vancouver, Toronto, and Montreal. I never thought it would be in Montreal, but it was and it was very successful.

ML—Why wouldn’t it be here in Montreal?

AO—Because this is where I got into all my trouble, in this province, when I was a child.

And now the show is in New York City. The first time I sang on a public stage was in New York City, at Town Hall in 1960. I was part of a group concert organized by Folkways.

I had been singing all my life, even as a young person, but just for friends and schools. Up on stage I was so nervous that I wanted to drop dead so that I wouldn’t have to sing.

ML—You went on to become a celebrated musician and activist, producing studio recordings and performing in hundreds of festivals, prisons, and universities around the world. Where did the passion to sing and share your voice come from?

AO—The system was so bad for native people, especially in school. Teachers would call us savages. I was the only Indigenous person in my class and the children really hated me. I got beat up a lot and was treated very badly. I figured out that education was the reason for ignorance, so it was very important for me to go into the classroom and tell the children a different story than what they were hearing officially.

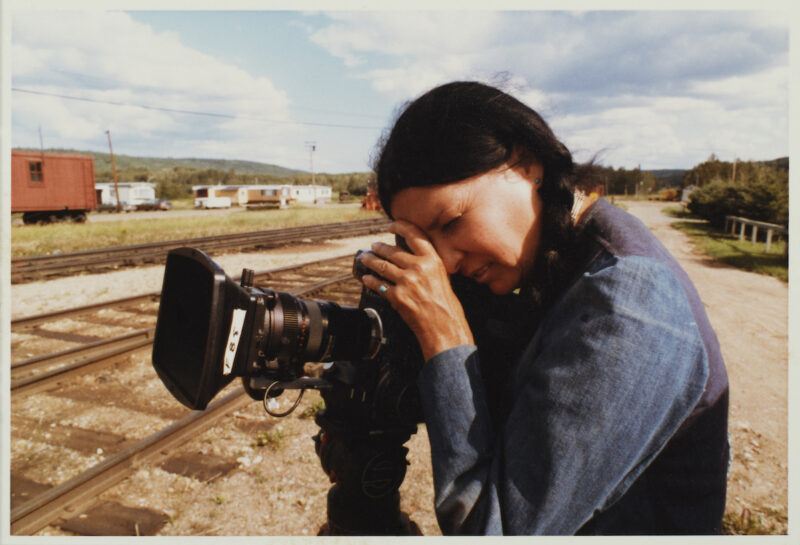

ML—What led you to begin making films?

AO—The National Film Board of Canada invited me here in 1967 because of a campaign I led to build a swimming pool for the Odanak community. Their rivers and streams were polluted and they were excluded from the nearby swimming pool, so I went to the Odanak chief and council and asked their permission to mount a campaign to build a swimming pool.

A filmmaker made a documentary about this campaign called Alanis, which was shown on a primetime CBC channel in 1966. Eventually, we were able to build the pool. After seeing that program on CBC, the National Film Board contacted me. The next thing I knew, I was talking here at the National Film Board of Canada, just like I was in the schools. I was giving lectures and singing, and it was the same kind of thing.

I didn’t say, “I’m going to become a filmmaker.” But eventually they gave me a contract to be a consultant, and that’s how I started. I’ve been here ever since.

Back then, when films were being made about our people, the people never really talked. When I started making films, I made sure that our people would be heard, and how we speak our languages.

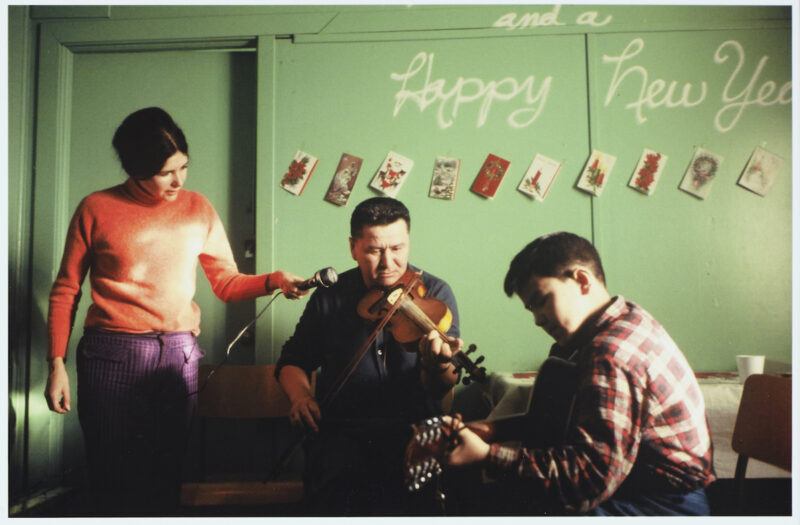

ML—Voice is so important in your work, particularly in Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), where sound design also brings so much to the film. I especially loved the field recordings of kids sledding in the snow. It’s so precious. Could you tell me about Christmas at Moose Factory?

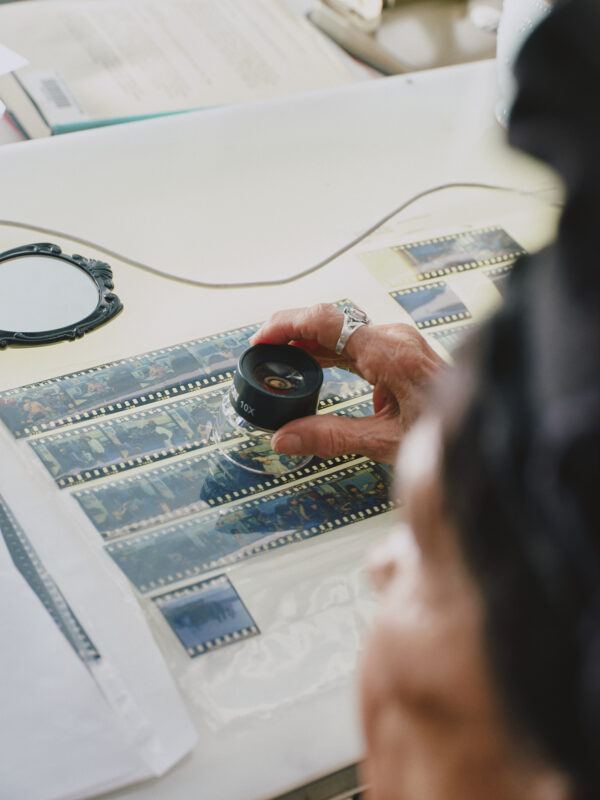

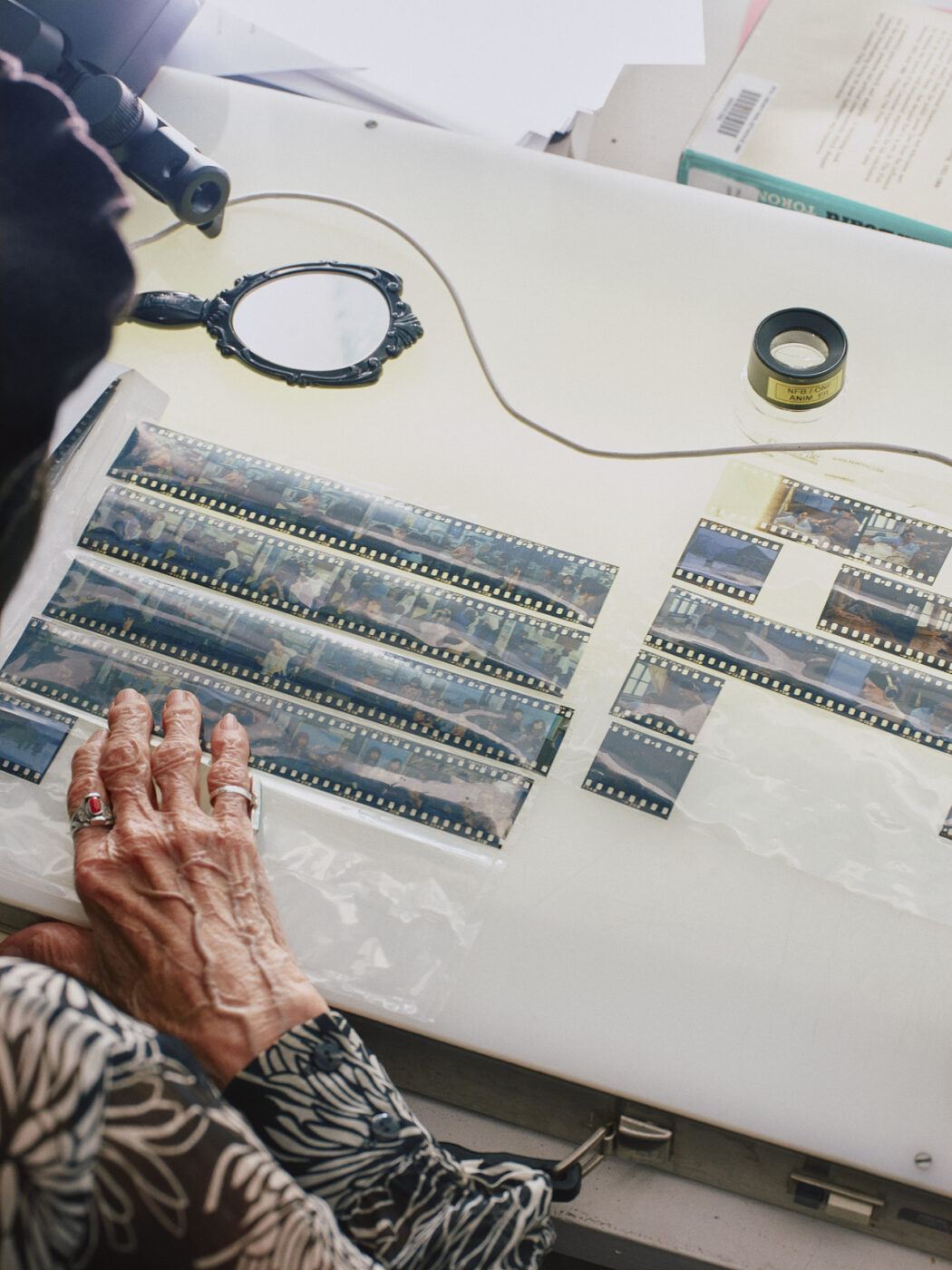

AO—This is the first 16 millimeter film I made. It took me a long time to finish it, because I had to raise money before the Film Board would match what I raised. I did all the sound for that film myself, and I was taping the children all the time.

I stayed in Horden Hall, which was a residential school 1 where the children slept. I went around Christmastime for three years in a row, and I would sing for them every night and tell stories. I became so close to them I was almost a relative.

One year, I said to the children, “I told you all my stories. Now, it’s your turn to tell me stories.” They became the storytellers, and that’s how the film was made. It’s beautiful to hear the way they speak.

ML—Some of your earliest work at the National Film Board of Canada was the creation of educational films and filmstrips that document different traditions and cultural practices of Indigenous communities. Could you tell me about that work?

AO—For one of these projects, I spent time with the Interior Salish people in Mount Gore, British Columbia. I did six or seven films and a filmstrip. At one point, I met this woman, Marie Leo, who was the last woman to have experienced a very important tradition when a girl starts menstruating. I said to her, “Okay, we’ll just record with sound, and you describe what you went through and how it starts.”

She told the whole story about menstruation with so much love and respect: she described that when you menstruate, you have the highest power in the world because you can give life. That’s not what I had heard in town growing up, and it was beautiful. I made a filmstrip about it, and I said, “Marie, you’re going to have to make drawings, because there’s no way I will find images of what you went through.” She said, “I can’t draw.” I said, “Oh, yes you can.” I had her stay at my house for a week or so and she did all the drawings for the film. It’s beautiful.

I use these filmstrips about menstruation a lot in the classroom. I remember one time in a private school, the bell rang, and the nun said, “Well, we have to go to lunch now.” The kids all stood up and they said, “Oh, could Alanis stay? We are not hungry. We want to continue.”

You’re so shy when you begin menstruating, and everybody says bad things. I could see how they were all taking it in, in a manner of respect, and how beautiful that was.

ML—It seems clear that you were able to build trust with Marie Leo in order to work with her on this project. How do you go about building trust with your subjects?

AO—I would never come to a community or make a film about people without first going with a sound recorder to talk, so that they can get to know me and know what I want to do. Some people cry when they tell me about their lives, and for me, that’s sacred. Only later on, when I feel that I understand what the story is, then I come with a film crew.

ML—In The Children Have To Hear Another Story at PS1, your film Mother of Many Children (1977) is projected on the rear of the screen where Christmas at Moose Factory is projected. Can you tell me more about this film?

AO—In 1973 or 1974, a group of women working for the government in Ottawa, said, “1975 is going to be the women’s year. We have nothing about women. We want you to make a film about a well-known woman.”

So I listened to this and I said, “That’s interesting, but I don’t think I would make a film about a well-known person. I would like to make a film that goes from the beginning of life to the end, speaking with as many women as possible from different nations in Canada.”

While filming, a friend offered for me to meet her elderly aunt so she could be in the film. So we go to this house and knock on the door and about four or five children come to the door and they see me and scream and run away. Then a woman came over to the door and she said, “Oh, Alanis, we know you. The kids were just watching you now on Sesame Street.”

So the kids, when they saw me on TV and then again at the door, they thought I was a ghost.

Then this woman, who must have been in her 70s, introduced me to her mother, who spoke only Cree. She was 107 or 108 years old. You see her in the film walking with her daughter next to her and a bunch of kids. She said to me, “Did you know that the Creator had a lot of affection for the woman? This is why He made her mother of many children.”

It was poetry. I can’t say anything else. And I finally made the film. I couldn’t go to all the places I wanted, but it’s an important film.

ML—There are so many powerful registers of your work in the exhibition: the whimsy of the children’s films and then the more sober treatment of trauma and violence in the documentary work.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), which documents the standoff between land defenders, Quebec police, and the Canadian Military, is in the center of the exhibition in New York. The film is an intense reckoning with colonial state violence and with plenty of contemporary resonance, and it is the only screening room in the exhibition with auditorium seats and red curtains. How did you design that film to be both a measured educational film and a record of a flashpoint?

AO—This is the history: it didn’t happen overnight, this resistance, it’s been there a long time after Kanehsatake, it was a different feeling for leaders of all the different communities, like being stronger and that we could fight back.

When All the Leaves Are Gone (2010) is later in the exhibition. It’s a story about me as a child, and the hostility of my days in school because I was Indigenous. One day when I visited the galleries, there was a man and a woman and three children watching the film. One little boy looked maybe four years old, and his mouth was totally open, you wouldn’t dare pass in front of him. That made my day because these are children’s films, and it’s important to reach the children.

ML—What are you working on now?

AO—My Friend the Green Horse is a new film that I made for children about a dream I had. It’s coming out now, and we did it in our language, in Abenaki as well as French and English.

ML—Have dreams always been important to you?

AO—I think dreams saved my life. I was treated very badly when I was young, but when I was asleep, I had another world.

Support for Art21’s READ comes from the Fleischner Family Charitable Foundation.

Interview conducted for Art21 in May of 2025 by Max Levin. Original photography for Art21 by Jodi Heartz and Alex Blouin. All other photography courtesy the artist, MoMA PS1, and the National Film Board of Canada.

Max Levin is an artist and curator based in New York City. He organizes programs at the Emily Harvey Foundation, and his writing appears in e-Flux Criticism, BOMB, MUBI Notebook, Screen Slate, and the Los Angeles Review of Books.