Deep Focus

Flickering Memoirs and Surveys: An Interview with Bill Burns

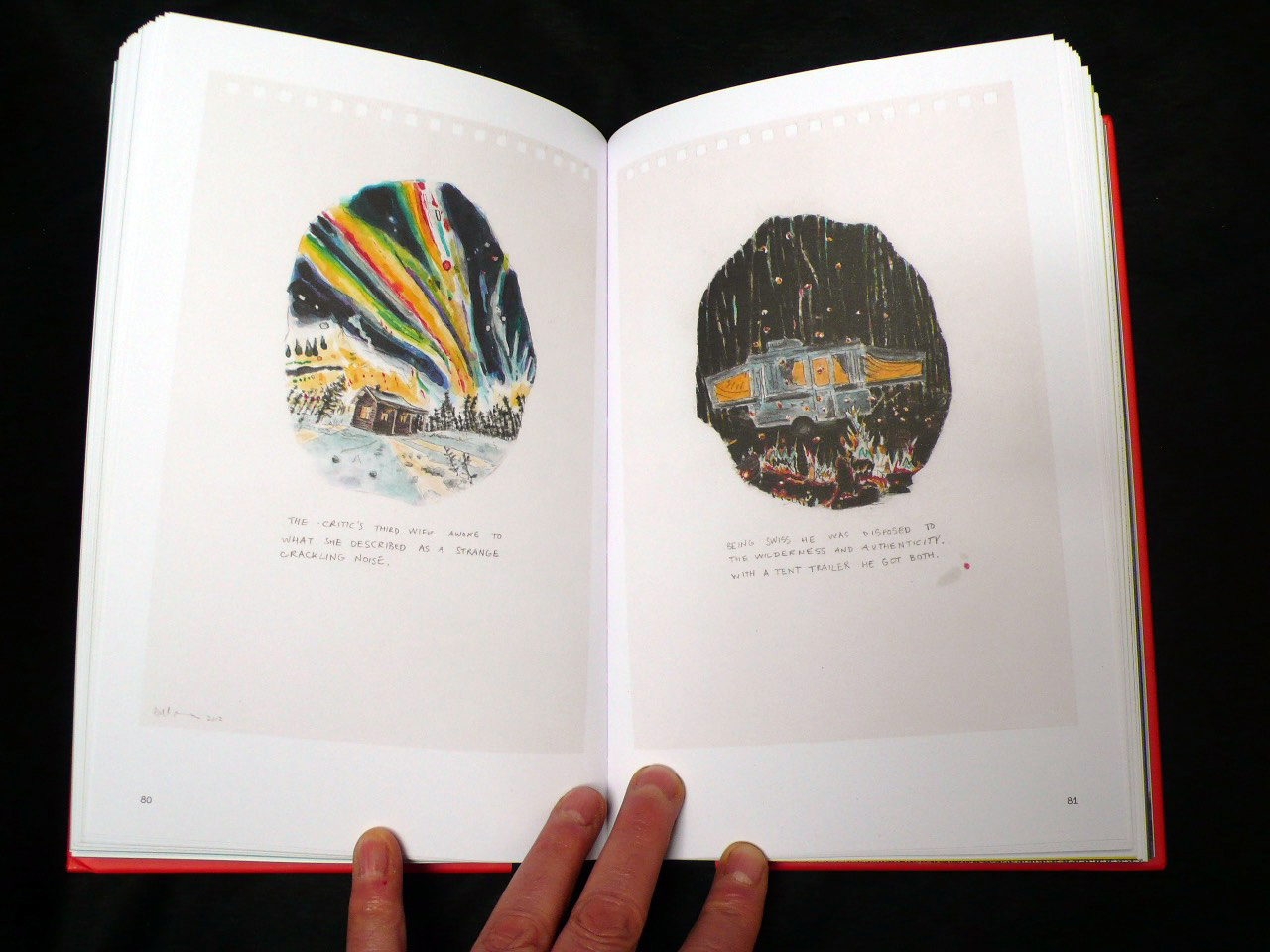

Bill Burns. The Critics Third Wife and The Swiss Collector and the Tent Trailer, book detail, 2014/2011.

The survey publication presents complex questions: what to highlight and what to discard? And, perhaps more importantly: how does one communicate one’s self to future audiences? Hans Ulrich Obrist Hear Us (Black Dog Publishing and YYZ Books, 2016) is Bill Burns’s answer. Part memoir, part artistic survey, this lush hardbound volume teases out the inception, development, exaltation, and ambivalence of Burns’s artistic life, characteristically mixing documentation, critical reflection, and embellishment to revise the archetypal artistic protagonist. Contrary to the fiction of the solitary artistic genius, today’s artists are bound within a network of cultural capital. Hans Ulrich Obrist Hear Us features writing by Dan Adler, Dannys Monte de Oca Moreda, and Jennifer Allen, with a foreword by Jennifer Matotek and Stuart Reid.

Caroline Picard—In the book, your autobiographical essay feels equivalent to the documentation of the surveyed artworks. And yet, there is something about the way that the essay, being a text appearing alongside others written by curators and art critics, has a different authority.

Bill Burns—Yes, the essay is a text in a different way than the pictures are. The essay is really a story about an artist (me) who is part wide-boy and part brownnoser. He is driven by a desire to be part of international art biennials and to be a player in the art world. His memoir transpires, for the most part, in sequence. Like most narratives, it has an internal logic, and in this case, they are based on a true story. It’s the story of my life as an artist.

Would you say your watercolors are also stories?

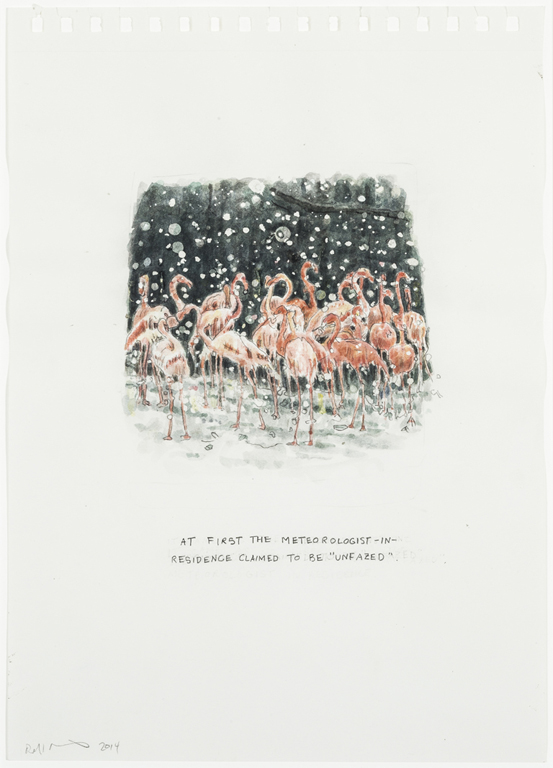

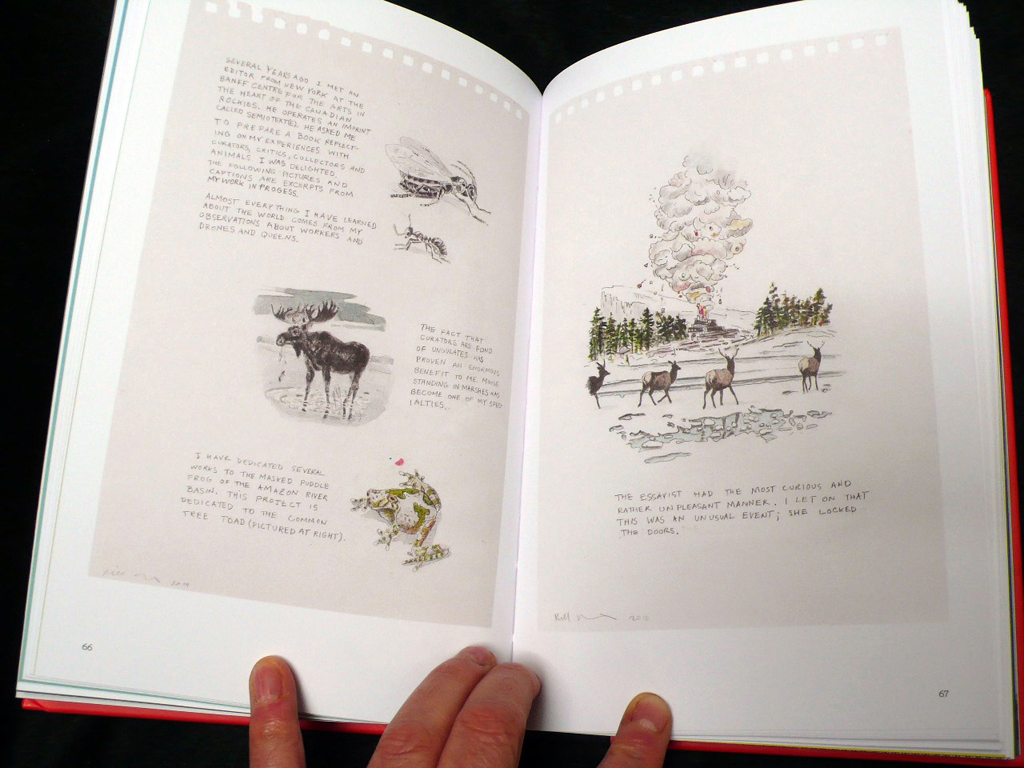

The watercolors are also true stories, but they operate as non sequiturs; they follow one from the other but don’t necessarily contain an internal logic. So, I suppose they are quite different from the written text. The pictures are mostly wildlife and nature scenes, but the captions refer to seemingly unrelated professional or career events, like a hike or a camping trip with an international curator. The indexes are mixed up—not too much but enough to make the reader question and maybe doubt their accuracy or truth. For instance, a picture of several mule deer watching a geyser erupt is paired with a caption about my annoyance with a certain essayist. Maybe the pictures demand more of the reader. They don’t make as much sense as the essay.

This makes me curious about how you are creating additional juxtapositions within the book. There isn’t just a single image with captions but also a series of captioned images, plus your autobiographical story, plus additional essays written by others, and additional photographic documentation…

Books are objects that you hold: you are in close quarters with the words, and, in the case of pictures, especially small, detailed pictures, this experience of being in close quarters is important. For me there is also a devotional element in the work. My essay shares its title with the book, and many of the pictures refer to prayers, invoking my desire to communicate with those in power, like a supplicant’s relationship to saints or a god. This brings me to the notion of books as intimate, and the memoir form is perhaps particularly so. Our relation to a book is solitary. Like the experience of a reader of an illuminated prayer book, it is also contemplative.

With that in mind, I am sensitive to the way your autobiography is choreographed: there is a mythic quality to it. At the same time, the essay is remarkably short–you skirted the tendency to write a whole epic and lengthy narrative! (I’m suddenly reminded of Wolfe’s Look Homeward Angel.)

In my essay, I note that people from Saskatchewan don’t talk much; I suggest this as a function of culture. There, people talk about when it’s going to rain, or when the rains will stop, or about blowing topsoil, or the price of grain. Whatever the reason, people from those parts are rarely loquacious, and my personality more or less fits this mold. That may explain my short-windedness.

That makes sense, although an unexpected romanticism runs through that brevity.

The first movie I ever watched was Lust for Life, the story of Vincent Van Gogh, played by Kirk Douglas. The Van Gogh character is obsessed with painting pictures of what he saw, but what he saw and depicted was completely misunderstood. Van Gogh’s tragic failure somehow appealed to me. And those who have seen the movie can attest that it is a story of passion, violence, and relatively few words. That was my first experience of a representation of the artist’s soul. My interests later turned to avant-garde artists such as William Burroughs and Joseph Beuys. In retrospect, all of these artists construct rather elaborate stories about their lives and, to some degree, their souls. The voice in my essay took this as its cue. The voice is at first self-aggrandizing, then humble, then concerned with the welfare of animals, but the narrator always seeks to advance his career. In some ways it’s the voice of neoliberalism.

It is interesting that Safety Gear for Small Animals does not appear in this book. How did you decide which works to include?

That long-running series of bespoke safety gear for small animals is my bread and butter, and I still show the works regularly. I mention the safety-gear project in my essay as a formative career event, but I don’t include any pictures of the equipment in my book. I kind of work around it, through my visits to the wilds and my hiking adventures with curators, museum professionals, and biennial directors.

That seems like an important decision, especially as you so directly address the question and development of your career. One would presume your choice would be to feature Safety Gear all the time; I appreciated the surprise.

I think of Safety Gear for Small Animals and Hans Ulrich Obrist Hear Us as ciphers for neoliberalism. Through producing and selling safety equipment such as respirators and vests, the project is dedicated to saving animals threatened by advanced industrialism by mitigating the deleterious effects of it. The project is at once well meaning and wrongheaded. I think of the new book as a way to mark our place in the current regime.

The title, Hans Ulrich Obrist Hear Us, is based on an artwork of the same name, for which you hired a plane to circle around Art Basel Miami Beach with a banner featuring the same text. There is something very different about the phrase appearing in the sky above an art fair versus appearing on the cover of a book of your work—perhaps especially because Obrist’s name appears so much larger than yours.

I tend to be a little loose with the titles of works. I have used the titles Hans Ulrich Obrist Hear Us, Beatrix Ruf Protect Us, and Okwui Enwezor Graciously Guide Us to refer to a set of projects and events. They use names of respected curators. The invocations paired with the names are standard prayer forms known as litanies; they belong to most Abrahamic religious traditions. And yes, two or three years ago, I hired an airplane to fly advertising banners of these invocations at Art Basel Miami Beach. It was a lot of fun. I heard from a friend that Adam Weinberg, the director of the Whitney Museum, came upon his advertising banner (that read “Adam Weinberg Remember Me”) completely by chance; he was flummoxed. I have also used large electronic billboards and commercial signage to ask for intervention from internationally renowned art players. Again, they were like appeals to saints or gods. But, as you know, these people are only celebrities in an art subculture, so these works are also jokes about how important we make ourselves out to be. One thing I’m pretty certain about is that this celebrity, and the type of counter-intuitive connoisseurship that goes with it, is unique to our moment.

As you mentioned, about your watercolors, much of your work has an ecological bent. Yet you’re also interested in teasing out or pulling at the art-world economies, for instance, with your Art World Celebrity Work Glove Collection. How do these poles of interest function and fluctuate together?

I’m glad you asked me about this. Yes, my work has an ecological bent, and I do see this as part of or at least connected to the economy of the art world. The loss of plant, animal, and other species is an ecological tragedy, but it is also a cultural one. When I imagine our literature or art [populated by] only Atlantic salmon, coyotes, rats, pigeons, and cockroaches, I get nervous. I think the unified regime of global capitalism is at play in both the destruction of the biosphere and the shrinking of the public sphere.

How so?

When I mess with the art world, my main concern is our shrunken public sphere, but I rarely think of these two spheres [the biosphere and the public sphere] as separate. Artistic discourse is often silenced by opaque power structures—by, for instance, public-museum board members who are interested collectors. Transactions that would be criminal in most fields are normal in art. In short, what was considered public during Joseph Beuys’s or William Burroughs’s lifetimes has been privatized. I think we can see the same forces at play in what was once considered the commons, like wilderness or fresh water. Global capitalism is our common sense.

You’ve brought neoliberalism up a few times in relation to your work. Can you say more about what you mean?

I think it really speaks to our condition, this common sense of global capitalism, in which finite resources are increasingly controlled by fewer people: our possibilities seem limited. Our condition, under this regime, is sometimes characterized as schizophrenic because we hear more than one voice at a time. As I said earlier, the narrator in my essay is part wide-boy and part brownnoser. The boy is an entrepreneur, always on the make, while the brownnoser is a supplicant.

I’m interested in the rapid flicker of ambivalence in your work, almost like a pulse between resistance and surrender, irony and sincerity, nature and culture (as happens literally with the “natural” images and the art-world captions), or critique and adulation. The flicker of those poles complicates the binaries. In your title, for instance: on the one hand, Obrist is appealed to as a kind of saint; on the other, I feel this phrase is a critique of curatorial celebrity and how it reflects exclusivity in the art market. So, your appeal seems slightly ironic. Additionally, your critique becomes more complex if one imagines that someone in a bookstore might quickly pick up your book and assume that Obrist is directly involved in the publication (since he writes so many books!). Can you say more about this tension that exists between the desire to be validated (and thus seeking the one who can validate), some ambivalence about the system of validation, and nevertheless benefiting by virtue of proximity to the validator’s name. It seems like a very tight network that is difficult to reject.

Thinking of the tension as a flicker is a nice way to put it. All those things you say ring true. You can imagine this is something of a problem. My approach is sincere, but you’ve put your finger on it: I’m conflicted. I think this sense of conflict, these multiple voices, is a commonplace. I’ve tried to bring this forward with my memoir and my pictures. There are strategies in my book: for instance, a to- and fro-ing regarding the urgency, and a conflation of lack, desire, nature, and political economy. The narrator is forever on the make—polishing apples for those in power. But these conflicts are not unique to artists. Many of us, including celebrity curators, share them. I try to listen to all those voices and to let others know how I feel. I consider it my job.

Bill Burns’s work about art, animals, and advanced industrialism has been shown at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London; the Museum of Modern Art, New York; KW Institute for Contemporary Art, Berlin; the Seoul Museum of Art, Seoul; and the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam.